Planning Assumptions: Are They Really Necessary and Valid?

We have seen mission-analysis briefings for years that include a slide titled “Facts and Assumptions.” The facts (bearing on the problem) are generally easy to identify and make sense of, primarily because they are just that, facts – evidence that stands on its own merit and needs no other confirmation because it is provable. Assumptions, on the other hand, are not currently provable but are based on sound logic, high probability of occurrence and applicability to the problem set.

However, it is common to dismiss many of the initial facts or assumptions because they are neither necessary nor valid once we look critically at them. This article expounds on the criteria of necessary and valid and proposes that the best venue for addressing assumptions is actually at the beginning of course-of-action (CoA) development rather than during the mission-analysis briefing.

Defining ‘necessary’ and ‘valid’

In a typical practice scenario where U.S. forces are moving into a contested area during an irregular-warfare environment, typical assumptions often include comments such as “The guerrilla forces will attempt to interdict and disrupt coalition forces with complex ambushes and improvised explosive devices,” or “The host nation will be able to provide potable water to meet our unit’s needs.”

While both of the assumptions may be true and even valid, they do not meet the requirement of “necessary,” thereby making them of no real value to our decision-making process at this point. Usually the facts and assumptions listed during the mission-analysis briefing rarely pass the “so what” test. The purpose of listing them is to allow the commander and staff to continue with the planning process in selecting a CoA.

The U.S. Army’s Commander and Staff Officer Guide (Army Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (ATTP) publication 5-0.1) defines facts and assumptions: “A fact is a statement of truth or a statement thought to be true at the time. Facts concerning the operational and mission variables serve as the basis for developing situational understanding, for continued planning and when assessing progress during preparation and execution. In the absence of facts, the commander and staff consider assumptions from their higher headquarters and develop their own assumptions necessary for continued planning. An assumption is a supposition on the current situation or a presupposition on the future course of events, either or both assumed to be true in the absence of positive proof, necessary to enable the commander in the process of planning to complete an estimate of the situation and make a decision on the [CoA].”

This begs the question: “Why then are assumptions listed during the mission-analysis process when we have not yet begun any planning of CoAs?” Perhaps they should be one of the first items briefed during CoA development instead. The reason for this is CoAs are often based on certain conditions being present for the CoA to be feasible, suitable or acceptable. Since CoAs should be distinctly different from one another, they will usually be predicated on distinctly different assumptions.

Example: In a CoA where a light-infantry battalion is considering an air-assault operation, a key assumption might be made about the amount of aircraft available for the mission. This assumption will normally not be encountered during mission analysis but will rather be determined when the unit begins planning possible CoAs, therefore making a validity check on the feasibility of this assumption necessary to proceed with CoA development. Since this is necessary to continue planning the mission, the staff must now ensure the planning figure is valid. So what constitutes the validity check?

The American Heritage Dictionary defines valid as “Containing premises from which the conclusion may logically be derived. Correctly inferred or deduced from a premise.” Using this as our standard for valid, the way to check for a valid planning figure of the number of available aircraft would be to seek expert advice (correctly inferred) such as from the brigade aviation officer (the logical person to ask).

‘Bell curve’ planning

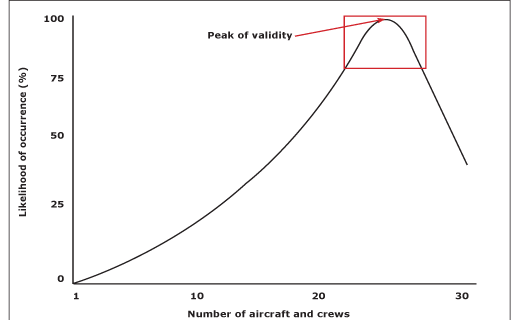

The trick here, as with any assumption, after proving that it is necessary to continue planning, is to make a judgment call on the “degree of validity.” Just how many aircraft (and crews) will be available for the air assault three days from now? Figure 2 represents a way to look at determining the validity of an assumption; view it as a “bell curve”-style graph.

The horizontal axis (x) represents the number of resources available (aircraft and crews). The vertical axis (y) represents the likelihood of occurrence (degree of probability). The curve represents the degree of probability of any likelihood of occurrence. At the left end of the chart, there is a low occurrence the unit would have less than 10 aircraft available (<25 percent). At the far-right end, there is a still-low-but-somewhat-higher chance of having all 30 available. Each end of the curve represents figures that would likely make the assumption invalid because of the low likelihood of occurrence. Somewhere in the middle is the greatest likelihood of occurrence.

In this case, the brigade aviation officer believes that based on current operating tempo, maintenance schedule and crew management, there is a 75-percent-and-higher likelihood they should be able to put up between 23-28 aircraft for the mission three days from now. In the meantime, he recommends the brigade use a planning estimate of 25 aircraft (peak of validity) for CoA development. Thereby the assumption is listed as “The aviation battalion will have 25 aircraft available for the air-assault mission.” This assumption is now considered valid.

The same “bell curve” principle can be applied when making other assumptions. Example: In a situation where an advancing armored force is facing whether or not enemy forces will blow the bridge-crossing sites before its arrival, one of its CoAs is based on capturing the bridges intact, but a second CoA has as an assumption: “The enemy will blow the two Class 100 bridges leading into the objective area.” (In this case, the statement might well be determined during the mission-analysis process since the intelligence officer developed it during intelligence preparation of the battlefield, but it requires further exploration to determine its full impact on the unit. This will occur in CoA development.)

In this case, planning a river-crossing contingency is now necessary, and the check for validity is “Do we have the available means and resources to conduct a river-crossing operation without using the two Class 100 bridges? If so, what are those means and resources?” The advancing armored force must now determine what gap-crossing assets are available to its force. (Everything from helicopters to secure the far side to rubber boats and assault float bridging.) The type and amount of resources available will then determine the unit’s possible CoAs.

Using the bell-curve principle, the x axis would be the amount of each resource (helicopters, boats or bridging), and the y axis would be the likelihood of getting those assets, and how many of them. After coordination with the appropriate liaison officers, a planner can then determine the valid planning figures for CoA development. In this example, planners consulted with the appropriate liaisons and developed their list of valid assumptions that read:

- No helicopters will be available to secure the far side.

- We will have 12 eight-man rubber boats.

- We will receive operational control of a multi-role bridge company from X Corps.

Key points

Based on this information, the staff begins developing CoAs based on current facts and assumptions because they are necessary to continue planning. Unless the resources change, the CoA must be planned within the limitations of available resources. Any CoA using planning factors outside the current assumptions invalidates the CoA. What makes the assumption valid is the research that planners did with outside units to see what the likelihood of occurrence would be for the force to get those assets.

Key points:

- An assumption is necessary to allow the unit to move forward with planning.

- An assumption is valid when some reasonable amount of research has been done to determine the likelihood of its occurrence.

It is unlikely these assumptions would have been fully developed during the mission-analysis process, therefore since each CoA is different and is based on different assumptions, we should consider saving the “Facts and Assumptions” slide for the beginning of CoA development, where we would have uncovered more detailed and meaningful information.

Notes

1 ATTP 5-0.1, Commander and Staff Officer Guide, Sept. 14, 2011.

email

email print

print