Combat in Cities: The Chechen Experience in Syria

Dr. Lester W. Grau, SFC Kenneth E. Gowins, Lucas Winter, and Dodge Billingsley

During the early part of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), analysts were quick to see Chechens in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other hot spots outside of Chechnya. Actually, the Chechen combatants were still at home fighting the Russians who had joined the Global War on Terrorism with the specific goal of completing their mission of subjugating Chechnya. They were in the third year of their second war in that small, mountainous country. Now, the Russians have reconquered Chechnya, and the republic is ruled by Ruslan Kadyrov, a former Chechen rebel who considers himself a protégé of Vladimir Putin and on very good terms with Russia. Although a few remain, many of the anti-Russian, anti-Kadyrov Chechen combatants have left the tiny republic, and some of them have taken up arms in other countries. Currently, at least three Chechen “battalions” are engaged in fighting against the Syrian government, and some individual combatants are part of ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant). These Chechen are sharing their combat-in-cities tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) with other rebel groups trying to overthrow the Syrian and Iraqi governments.

How Did the Chechens Become Involved in Fighting in Syria and Iraq?

There are three factors worth consideration. First, the Chechens have a recent history of fighting in foreign conflicts. Both Shamil Basaev and Ramzan Galaev brought their “battalions” to Abkhazia in 1992 to fight on the Abkhaz side of the conflict. Chechens were also present in South Ossetia in 1991 and in Nagorno-Karabakh around the same time. Although some speak of high-minded ideals to justify their foreign involvement, for many, life as a fighter was simply better than civilian life in Chechnya.1 Long-held “warrior” ideals prevalent in Chechen society also cannot be underestimated when the call of foreign combat presented itself. Eventually these Chechens returned to Chechnya with combat experience and became the backbone of the Chechen resistance when Russia tried to pacify the rebellious region in late 1994. So, a history of foreign involvement isn’t new to the Chechen warfighting experience, and many still see it as a better alternative to life in Chechnya under Kadyrov. Isa Manaev, the previous “Defender of Grozny” during the Second Chechen War and a staunch nationalist who rejected Islamic radicalism, recently fielded a Chechen volunteer battalion in Eastern Ukraine. He is one of a handful of non-radical Chechens now sharing their fighting experience in Ukraine.2

The second factor to consider is foreign intervention within Chechnya itself. During the First Russo-Chechen War (1994-1996), Thamir Saleh Abdullah Al-Suwailem came to Chechnya. Known by his nom de guerre of Ibn al Khattab, Thamir was a Saudi Arabian who had fought along with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan. But it was after Afghanistan, while fighting in Tajikistan, that Khattab first heard about Chechnya. He arrived in Chechnya in the spring of 1995. Originally he linked up with Salman Raduev, but that relationship was short lived and he eventually formed a close friendship with Shamil Basaev. As a result, he moved his whole operation into the Vedeno Rayon, ancestral home to the Basaev clan. He immediately proved to be a very effective fighter and battlefield commander, and dozens of foreign fighters followed him to Chechnya while many Chechen combatants gravitated to him as well.3 At the start of the First Russo-Chechen War, the average Chechen insurgent was nominally Islamic, drank vodka, smoked, and fought the Russians with the intent to break free of Russia and establish an independent Chechnya. Khattab established a school and training camp near Serzhen-Yurt and in addition to battlefield TTPs taught Wahhabism, a radical militant form of Islam at odds with the Sufi tradition of the Chechen people. Still, because of his battlefield prowess, Khattab and his followers were more or less accepted. The handful of Chechens who attended his training camp and fought alongside him were indoctrinated not only in the fine art of tank destruction but also radical Islamic study.4 This continued through the interwar period (1996-1999).

During the Second Russo-Chechen War (1999-2009), serious divisions within the Chechen resistance began to emerge. The “laid-back” Chechen nationalists were faced with a disillusioned, ideologically charged often younger generation of Chechen combatants hardened by years of war and more easily radicalized. Chechnya had a population of some million people. Combat attrition had impacted significantly on the nationalists. As many as 600 Chechen combatants were killed during their withdrawal from Grozny in January 2000. In March of the same year, another 800 Chechen combatants were killed in fighting in Komsomolskoe. Many senior combat leaders had been killed and replaced by younger leaders. The new leaders and many of the surviving old leaders were changing the message from separation from Russia to trans-regional Islamic jihad. Khattab and his other foreign jihadists continued to play a significant combat, training, and indoctrination role until 20 March 2002 when Khattab was killed by a poisoned letter arranged by the Russian security services.5

Khattab was replaced by another Saudi, Abu al Walid. Khattab and Walid had taught the Chechens spiritual restraint and pushed a focus on cleanliness of spirit and intent, which were considered critical to effective jihad. The Chechens were also very successful with their media campaign until the Russians shut down media access. Khattab travelled with a camera crew that he used for information warfare operations and to secure further funding and recruits from abroad. These are some of the same information operation tactics now being used to greater effect in Syria and Iraq due to a more robust global internet capable of disseminating information nearly in real time anywhere in the world.

Finally, the third factor to consider regarding Chechens fighting in Syria and Iraq is that some of the most notable Chechens fighting in Syria and Iraq are not technically Chechen but Kists from the Republic of Georgia’s Pankisi Valley and Gorge. The Kists are a close relation to the Chechens and are often referred to as cousins. During the wars with Russia, the Pankisi Valley was a refugee destination but also a sanctuary or “R&R” location for Chechen combatants taking a break from the fight up north. It was well known that Galaev would take his whole battalion to the Pankisi. Other Chechen combatants also made their way south to the Pankisi. In addition, it was a way station for foreign fighters seeking to get to Chechnya. The fact that important Chechen combatants fighting in Syria and Iraq are not even Chechen but rather Kist attests to the spread of Chechen influence and also TTPs beyond Chechnya, beyond the Caucasus, and now into the Middle East. Take the case of Umar Shishani, a Georgian national born Tarkhan Batirashvili and raised in the Pankisi Valley who is now a military leader in ISIL. While some might shrug off the differences between Kists and Chechens, it matters to Chechens. And if accurate intelligence matters, it is important to note that Umar Shishani represents another brand of Chechen combatant — one who takes on the banner of being Chechen with all its credos, ethos, and reputations but without actually being a modern-day Chechen and having little or no Chechen war experience. This next generation of “Chechen” fighters seems content to carry the Chechen banner into new conflicts with their goals being far from the original aspirations of Chechen independence.

Today, the success of the hard-line rebel groups, as well as ISIL, seems to rely on their simplicity of message, or Islamic purity if you will. ISIL combatants are not the same people the coalition fought during the last 13 years in Iraq. The foreign-fighter presence is significant in numbers and in the capabilities they have given to ISIL. Rebel groups that couldn’t place three people on the street in the beginning without drawing regime attention are now present in force. In many respects they are more dedicated, harder, confident, more goal oriented, and better prepared.

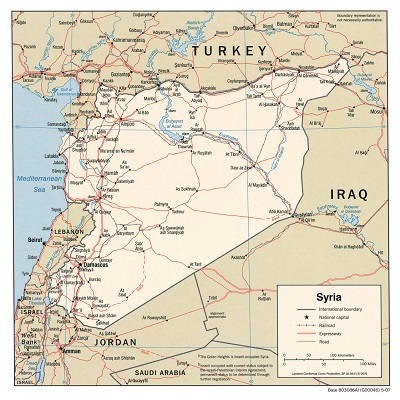

The translated article that begins on page 35 describes fighting in Syria’s Aleppo districts of al-Zahra and Leramon beginning in March 2014.7 The rebel offensive aimed to take over the city’s Air Force Intelligence (AFI) headquarters (HQ). The AFI HQ was part of a large complex that included a massive construction that was to be Aleppo’s future courthouse (or “justice palace” and which the article nicknames “the skeleton”), the Syrian Red Crescent Building, the Technical Services Building, an orphanage, a mosque, and an electric sub-station. The AFI HQ was considered a key operations center for the Syrian government in Aleppo and was located on the northwest edge of the city. It was the bulwark protecting the northwest entry to the government-controlled western half of Aleppo; the northwest countryside all the way to Kilis across the border in Turkey was largely in rebel hands.

The toughest fighting was building to building in the district of al-Zahra (Jama’iat al-Zahra or “al-Zahra Cooperative”). The neighborhood housed government supporters including AFI employees. It was a modern area consisting of wide boulevards and blocks of identical square, multi-story commercial-residential buildings. Schools, mosques, and empty lots provided occasional open spaces between the buildings. This is a very different type of urban setting than Aleppo’s core, which is dominated by narrow, winding alleys. Rebels took over the “Leramon Halls” to the north of the AFI HQ in April while making slow and gradual progress, fighting building to building from the south and the west.

In late April, the Chechen-led Jaysh al-Muhajireen wal Ansar (JMA) claimed to have taken “the skeleton.” A video dated 28 April shows what appears to be a black flag fluttering atop the unfinished hi-rise, though it is unclear whether and for how long rebels held the building (see Figure 3). In mid-July, rebels released video showing a massive nighttime explosion that partially destroyed the orphanage in the AFI complex. Accompanying videos explain that a mined tunnel dug from the nearby frontlines had caused the blast. According to rebels, the tunnel was 15 meters long and had taken around a month to dig. Video evidence implies that the tunnel had been dug using a combination of electric and hand tools and that large quantities of fertilizer were used in the blast.

The rebel attack was launched by a coalition headed by the JMA and also included Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic Front (along with several other Syrian Islamist fighting groups). JMA field commander Mohanad Shishani was killed in the fighting.

The JMA first joined fighting in Syria as the “Muhajireen Brigade” in late summer of 2012. It fought in the Aleppo countryside and was led by Umar Shishani. In the spring of 2013, it merged with other groups to become the JMA and began collaborating closely with ISIS. In September 2013, a group of fighters led by JMA deputy commander Sayfullah Shishani split from the group, stating a desire to remain independent and given their pledge of loyalty to Dokka Umarov and the Caucasus Emirate. A few months later Umar Shishani openly pledged loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and ISIS. Within weeks a second faction split from Umar Shishani, once again stating a desire to remain independent and in light of their pledge of loyalty to Umarov. This splinter group, which was led by Salah al-Din al-Shishani, retained the JMA name and is the one involved in the Leramon al-Zahra fighting described in the article.

The March 2014 offensive coincided with two other Chechen-led operations: one an ongoing attempt to storm Aleppo Prison to the northeast (eventually broken by Syrian government forces), in which Sayfullah Shishani had been killed the month prior; the other a simultaneous attack launched by a different Chechen faction (Junud al-Sham led by Muslim Shishani) on the Christian Armenian town of Kassab along the border with Turkey in the province of Lattakia, considered Syria’s Alawite heartland. Umar Shishani (Umar “the Chechen”) has assumed the role of military commander of ISIL. The following is a translation from a Russian-language article on a Chechen website about urban combat. The author is a member of JMA, which is the Caucasus Emirate proxy force in Syria. It is labeled part one, so hopefully more will follow:

Combat in Cities: Experience from Syria and Chechnya8

This is data compiled from the experience of Mujahideen and unbelievers fighting in Syria and Chechnya. Although the data that is recommended here is for urban combat, much of it may and should be used during combat in other terrain (rural settings, mountains, gorges, and so on).

The common world-wide experience with military action in inhabited places shows that urban combat may be considered the most complex. It establishes harsh demands on tactical training, weapons, and munitions as well the morale of the combatants. Every building can become its own “fortified region” with multiple window embrasures, canalization traps, attics, and basements.

Technology gives practically no advantage to any army during urban combat. Individual training and the morale of the opposing sides is the first determinant in urban combat. The importance of technology trails on a secondary plane.

For the successful outcome of an urban combat mission, it is necessary that groups contending with a larger enemy force must have powerful weapons, reliable communications, and be well trained in tactics. The last requirement is the most important because insufficiency in tactics negates the value of the rest.

Every city is divided into regions and blocks. Modern buildings are often situated 90 degrees from each other, forming a box. Remember that when attacking these particular structures, it is best to attack the end of the building when engaging the defending security force. This stems from the fact that the majority of people shoot right handed, and it is easier for them to engage targets located to their left. If it happens, for example, that the building is located to the attacker’s right, the attacker needs to engage the target by firing left handed, which will be uncomfortable and ineffective. It follows that it is desirable to have left-handed shooters in every group. If this is directed by senior leadership and included in rear-area covering groups, it will make things more uncomfortable for the enemy. It is necessary to develop the ability to fire from the left shoulder (for right-handed shooters, for left-handed shooters just the opposite). This can be developed by initiating a training regimen whereby the shooter switches the stock from one shoulder to the other. One of our brothers, a former Spetsnaz who at one time fought against the Mujahideen in Chechnya, later trained a group of Ansar al Sharia [an offshoot of al-Qaeda] to shoot from the left shoulder. They did not do badly, and over time the majority of the Mujahideen in Syria developed the ability to shoot from the left shoulder effortlessly. At this time in Khurasan (Afghanistan, Pakistan), they are acquiring this ability.

When moving toward a building in a city, it is necessary to move alongside a wall or similar obstacle. Under no circumstance should one move down the center of the street. There is less chance of being hit by enemy fire (usually they fire down the center of the street, also there is less chance of being noticed moving alongside a wall) and you can move under cover more quickly from the side of the street. If you must cross an open space, it is better not to do it directly, rather move in circuitous fashion (the principle being not to move down the center of the street). If you need to cross an open space, move very quickly. When you have to run across a dangerous section covered by enemy fire, determine the distance of the danger zone that you must run across and the probability that the enemy is expecting you at this section and at this given moment. If the section to be crossed is not very big, then it is better to run across in groups of several men without maintaining set distances between the runners. In this case, the enemy may simply not react to your appearance. If the distance to be crossed is appreciably wider, then it is better to cross singly — one runs while the rest wait. If you run across in a small group, the enemy rifleman may notice you and simply fire into the crowd, and most often no one is hit. During fighting in the al-Zahra, Leramon in Aleppo, the brothers ran across a wide-open section in groups of several men. The unbeliever machine gunner fired into the group and wounded one brother. It is best of all to cross a dangerous section under covering fire. The covering fire is provided by brothers who do not need to run across the section or those who have already crossed. At first, one or several brothers take up positions to provide the covering fire, then the remainder run across in order. Those who have run over also take up firing positions to provide covering fire for those who have still not crossed over.

Always maintain distance from one another and don’t bunch up. One burst of fire, grenade, mine or mortar round may suffice to kill or wound everyone. During the spring offensive in the Leramon region of Aleppo, the unbelievers shelled our front line. Our brothers in the reserve were eating out on the street. In the distance, mortar rounds fell - one, two. One of the seasoned veteran brothers suggested that they take shelter in a building. The others replied that the mortar rounds had landed in another area. Then another mortar round dropped right on top of them, and several brothers became martyrs, God willing. Therefore, even if the mortar or artillery rounds land several hundred meters from you, it is necessary to move to shelter (building, bunker). The unbelievers may shift fires between the front and the depths.

Very often, in order to seize a particular building, it is necessary to capture the neighboring buildings since fire from them can block the advance of the assault troops. After accomplishing this action, those buildings which have their ends facing the target building can conduct surrounding fires. The space between the buildings is swept by fire, and often the ends of many buildings do not have windows.

Also, you can achieve an advantage if you are able to drive the enemy into the building located next to your force and are able to observe the stairwell. In this case, the enemy is unable to freely move between the floors since he is only able to appear on the stairs as an excellent target. In this case, you have locked the unbelievers in the rooms located away from the critical side of the building.

For example, the enemy reasons similarly to you. He is not interested in ground-level and uncomfortable positions. He is more attracted to the multiple-storied cement buildings towering over all the surrounding neighborhood, located next to wide streets or other open areas.

Thus it was at al-Zahra in the Leramon region in Aleppo. The unbelievers occupied a huge, unfinished concrete “palace of justice” (the brothers called it “the skeleton”), which has a tall, partial framework of a tower erected next to it. There was a large-caliber machine gun emplaced on the top floor. The unbelievers were able to observe in all directions for a long distance from the tower, which greatly impeded the Mujahideen. Enemy fire from “the skeleton” was one of the main problems. “The skeleton” was surrounded on all sides by wide roads. The closest distance between houses occupied by the brothers and “the skeleton” was 80 meters over open ground. We tried to take it several times, but finally it simply could not be done.

It is very easy to control the situation from the highest floor; everything that goes on in adjacent buildings and their surroundings is as visible as the palm of your hand. One can conduct effective fire from the top floor of a tall building; moreover destroying these firing points with small arms is very difficult. The primary dangers to us were the unbelievers’ tanks, “zushki” (the ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft machine gun either ground or jeep-mounted), and heavy machine guns.

Do not attempt to force a passage through the enemy defenses and penetrate deep into the territory occupied by the unbelievers. While capturing a few buildings, you may come under fire from three sides; or even worse, you may be cut off from the main body. This situation may be skillfully set up so that the enemy may lure you unwittingly into a trap. Not only is it forbidden for you to fall into these traps, but you also need to practice setting your own traps. The brothers in Aleppo used similar enticements into traps during the first months of fighting when the unbelievers did not stop falling for these tactical tricks. Also, the brothers fell into such traps in various locales. In 2013 in the city of Ra’s al Ain (in the Province of Al-Hakasan), the Kurdish murtad [apostate]-communists from the PKK (Kurdish Workers Party) used a trick against the brothers from the Jabhat al-Nusra organization to lure them into a trap and killed many brothers. The assault on the city collapsed, and the newly-arrived Mujahideen had to withdraw from it.

A very effective means is the use of a bomb to mine a building. For example, the building is mined so that the explosion not only razes the building but also weakens the enemy. One press of the button can bury more than a squad of the enemy. It is also possible to mine a building that the unbelievers are already occupying. Here, the principal problem is approaching the building (secretly or under the cover of fire) and the possibility of providing enough explosive material, the sum total of which is sufficient to destroy the building or a part of it, or, as a last resort, in order to deafen and confuse the enemy and/or to create an additional entrance for safe passage for penetrating into the building during an assault. We have received reports from the Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar [jihadist group of Chechens and other Russian-speaking fundamentalists] that during the spring fighting for the al-Zahra, Leramon region in Aleppo, the Mujahideen employed this method with great effectiveness.

There is the possibility of using underground passages to get under a building to mine it. Reports indicate that this is also very effective. This was and is being put into practice all over Syria. In Aleppo, in one instance, they blew up a tunnel containing 15 tons of explosives. The tunnel was under the Air Force Intelligence Headquarters in the al-Zahra, Leramon region. Tunnels were also blown up in Idlib, Damascus, and other places.

In Syria, there is also a widespread prevalence of digging tunnels for secret movement within cities. Newly dug tunnels are used to move between our own points and as secret approaches to the unbelievers’ positions. These are widely used for these purposes in Damascus and lately in Homs.

If an assault is going to be made under the cover of a smoke screen, you need to position the smoke charges after considering the direction of the wind. When the smoke densely shrouds the enemy front line, the group moves toward the end of the building they intend to assault (for security, they sometimes “scrub out” the passageway between the buildings with the use of directional [claymore] mines). Even the use of a thin smoke screen lessens the effectiveness of aimed enemy fire. This is especially so for snipers who rely on optical sights for conducting fire.

But it is necessary to remember that mistakes can put smoke on your own positions, and then the advantage passes to the enemy. It is particularly important to determine wind direction before using chemical and/or irritant agents with the goal of smoking the enemy out of his location or putting him out of commission. During the penultimate assault on the Minnag military air base near the city of A’zaz in the northern part of Aleppo Province, the brothers did not determine the wind direction and were struck by their own gas attack (they used police CS tear gas grenades fired from a special police grenade launcher designed to disperse demonstrators). Now, in summer, in northwest Syria, in the vicinity of Halab [Aleppo], the wind is predominantly from the west from the sea. It increases especially at night. It is necessary to study the wind before creating a smoke screen or using chemical/irritant agents against the enemy and to learn during firing where the firing points are, particularly for the snipers and grenadiers.

Also, it is necessary to study the wind direction when secretly moving closer to the enemy or conducting reconnaissance. You do not want to be heard, and therefore you need to approach the enemy from the leeward side (that is to say, the wind must blow from the enemy toward you). Thus the sounds that you make are carried off by the wind, and, on the other hand, the sounds that the enemy makes are more audible.

In Syria, as a rule, the Mujahideen use homemade smoke charges. The majority of them are unable to obtain factory-made smoke charges. They seldom use factory-made smoke grenades. I have encountered Soviet RDGs (smoke hand grenades) which have a cardboard shell with a cord connected to a friction ignition element (a giant match inside the smoke compound). If the smoke grenade does not ignite, simply light it with a cigarette lighter. The RDG produces two smoke colors indicated by Б (white smoke) and Ч (black smoke). The RDG black smoke grenade, when ignited without access to oxygen, produces deadly phosgene gas. The RDG smoke color is printed directly on the grenade as a large Б or a large Ч.

To drive out the enemy from his buildings, you might attempt the use of pepper-filled containers that are duct-taped to grenades. You may use the experience of Chechen Mujahideen who filled the interior of [RPG-7] grenades with crop-dusting insecticide or pepper (who does not know that the inside of the [anti-tank] grenade has a empty space, which functions to increase the penetration of armor). It is only necessary to bear in mind that the overall weight of the grenade has increased and the trajectory of the flight of the grenade is steeper.

The article ends abruptly, but this was supposedly part one with more to follow. Reading the article, one is struck by the return to basics with a few evolutions. During the fighting in Grozny, the mortar was the major casualty producer. Although a mortar did end the life of Sayfullah Shishani, this is not the case in Aleppo where the heavy machine gun seems to have that honor.9 The goal of having combatants who can fire equally well right- or left-handed is a Russian special forces technique that is used to fire around obstacles. It is trained as a movement efficiency skill that works due to the low sight line and shorter “Warsaw Pact” length stock on the AK series rifles. Whether or not this tactic was introduced into Syria by Chechen combatants isn’t clear, but two wars and a decade and a half later, Chechen combat veterans have had ample time and opportunity to study their enemy. Perhaps this was lifted from their Russian adversary. Muslim Shishani, Emir of Junud al-Sham, has openly stated that he continues Khattab’s work in Syria while Syrian rebels seem to be organizing tank killer teams that are modeled exactly as the Chechen teams of Grozny in early 1995. Finally rather than a route, the proclaimed “tactical withdrawal” of ISIL forces at Mount Sinjar in Iraq under heavy bombing smacks of Shamil’s exodus from Grozny so many years ago in March 1995 - an operation he himself described as a tactical withdrawal. This could be linked to the confidence of Chechen leaders who are quite familiar with Russian use of aviation and large artillery barrages and comfortable with riding them out.

The Chechens are not present in overwhelming numbers anywhere in Syria or Iraq, nor in ISIL. Nor are all Chechen combatants in Syria former combatants in Chechnya, but they are a product of the Chechen diaspora or have taken the moniker of “Chechen” - like Salah al-Din Shishani and Umar Shishani. However, they have “street cred” and a reputation to maintain. They represent a significant fighting capability with a strong track record in a combat force that is learning to fight by doing it and then taking what has worked since the initial street fights of Grozny in December and January 1994 to advance their ability in the current struggle for Syria and Iraq.

Notes

1 In an interview with co-author Dodge Billingsley in 1997, Shamil Basaev stated that he went to Abkhazia to fight because he believed that the Muslim Abkhaz people were in threat of being wiped out by Georgia. Interviews with other combatants with Abkhaz experience seemed to indicate that it was more something to do.

2 “Chechens Now Fighting on Both Sides In Ukraine,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 30 August 2014.

3 There were other Wahhabis who came to Chechnya before Khattab, but neither they nor Wahhabism gained traction. It wasn’t until someone with real battlefield credentials (i.e., Khattab) arrived and proved his worth on the battlefield that he was given the respect and place in the Chechen resistance. It must be remembered that Chechens prize the ideal of the warrior above most other attributes, and Khattab proved to be a man among men. These thoughts were conveyed to me by many combatants in Chechnya. Interestingly, Khattab actually said as much as well. Speaking to my interpreter, a Muslim from Africa, he told him that “the Chechens only respect two things, money and violence. They respect my ability to fight and otherwise I wouldn’t have a future here.” Billingsley interview taken in Salmon Basaev’s house (Shamil’s father) in Vedeno, November 1997.

4 Interview with Abu Bakar, a Chechen mid-level combatant who attended Khattab’s training camp near Serzhen-Yurt. Although Abu learned military tactics and the Quran, he claims to never have embraced Wahhabism. Dodge Billingsley. June 2008.

5 Dodge Billingsley with Lester W. Grau, Fangs of the Lone Wolf: Chechen Tactics in the Russian-Chechen Wars, 1994-2009 (Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office and Quantico, USMC, 2012): 4-7.

6 Kist identity is a bit like splitting hairs. Although there has been debate, many within the Chechen and Kist community consider them Chechens. As the story goes, they were Chechens who settled along the Kist River in Georgia several hundred years ago and over time have identified more with the larger Georgian community. Geography played a significant role in this. The fact that they reside on the southern slopes of the towering Caucasus mountains facilitated easier interaction with Georgian peoples rather than Chechens on the north slopes of the Caucasus. In addition, the carving out of international borders separating the Kists from the larger Chechen community aided in isolation of the Kist people. Finally, intermarriage in the Kist community has further separated them from the larger Chechen community. Umar Shishani has a Kist mother and a Georgian father. It wasn’t until the recent Russian-Chechen wars that there seemed to be a reawakening of the Kist’s Chechen roots.

7 It included two separate battles launched by rebels each with two stages. They were named: “al-itisam” and “batr al-kafirin.”

8 This report is taken from http://www.chechensinsyria.com/?p=22372. It is titled as “New Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar Essay: War in Urban Conditions: Experience From Syria & Chechnya” and was posted on 15 August 2014. It is based on Chechen fighting in the region of al-Zahra, Leramon region in Aleppo, Syria. It is written in good Russian by someone with a military tactical background. The Chechens involved in Syria are fundamentalist Sunnis [the brothers] whereas the “unbelievers” may be Russians in Chechnya or Christians, although the term is also applied to apostates in Syria - Sunni members of Sufi brotherhoods and Shia (including Alawites, Imamis, and Ismailis). Translated by Dr. Lester W. Grau, Foreign Military Studies Office, 22 August 2014.

9 Lester W. Grau and U.S. Navy CDR Charles J. Gbur Jr., “Mars and Hippocrates in Megapolis: Urban Combat and Medical Support,” U.S. Army Medical Department Journal, January-March 2003. Reprinted in the Journal of Special Operations Medicine, Summer 2003.

Dr. Lester W. Grau is a senior analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. He has served the U.S. Army for 48 years, retiring as an Infantry lieutenant colonel and continuing service through research and teaching in Army professional military education. His on-the-ground service over those decades spanned from the Vietnam War to Cold War assignments in Europe, Korea, and the Soviet Union to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. As one of the U.S. Army’s leading Russian military experts, he has conducted collaborative research in Russia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and with numerous organizations in Europe, and published extensively. Dr. Grau is the author of more than 14 books and 200 articles and studies on tactical, operational, and geopolitical subjects, which have translated into several languages. His books The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Combat Tactics in Afghanistan and The Other Side of the Mountain: Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet-Afghan War, co-authored with former Afghan Minister of Security Ali Jalali, remain the most widely distributed, U.S. government-published books throughout the long conflict in Afghanistan. He received his doctoral degree from the University of Kansas. His advanced military education includes the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and the U.S. Air Force War College.

SFC Kenneth Gowins is a 19D currently serving as a senior training developer/writer for Cavalry Branch Doctrine, Maneuver Center of Excellence (MCOE), Fort Benning, Ga. His assignments include serving as scout platoon sergeant for C Troop, 3rd Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment, Fort Benning (OIF V and OIF VII). SFC Gowins’ military education includes the Cavalry Leaders Course, Scout Leaders Course, and Maneuver Senior Leaders Course. He is the recipient of a Bronze Star Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, and Order of St. George bronze medallion.

Lucas Winter is a Washington, D.C.-based Middle East/North Africa research analyst at the FMSO at Fort Leavenworth. FMSO conducts open-source and foreign collaborative research, focusing on the foreign perspectives of understudied and unconsidered defense and security issues. Mr. Winter has published on topics including Yemen’s Huthi Movement, the microdynamics of the Syrian insurgency, Libyan regionalism, and al-Qaeda’s Lebanese affiliate. His work has been published in a variety of journals including Current History, Middle East Policy, Middle East Quarterly, CTC Sentinel, Small Wars Journal, and Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. He also contributes to FMSO’s monthly Operational Environment Watch. Mr. Winter has a master’s degree in international relations from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a master’s in Arabic language and literature from the University of Maryland. He was an Arabic Language Flagship Fellow in Damascus, Syria, in 2006-2007. Prior to joining FMSO, he lived in Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt.

Dodge Billingsley is the director of Combat Films and Research, a fellow at the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University, and a senior faculty member at the Naval Post Graduate School’s Center for Civil Military Relations. A long-time observer of many conflicts, Mr. Billingsley has spent considerable time in the Caucasus where he first became familiar with Chechen insurgent/separatist forces during Georgia’s war with Abkhaz separatists in 1992-1993. He has written extensively on the topic and produced two documentary films (Immortal Fortress: Inside Chechnya’s Warrior Culture and Chechnya: Separatism or Jihad?) based on his experiences with Chechen combatants. He recently conducted a number of interviews of former Chechen combatants for his current work, Fangs of the Lone Wolf: Chechen Tactics in the Russian-Chechen Wars 1994-2009.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print