Book Reviews

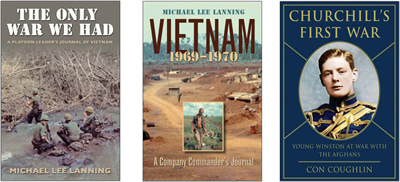

Churchill’s First War: Young Winston at War with the Afghans

By Con Coughlin

NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2014, 320 pages

Reviewed by MAJ Kirby R. Dennis

Followers of Winston Churchill are familiar with the many distinguished titles he held over the course of his life: Member of British Parliament, First Lord of the Admiralty, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and most notably, Prime Minister of Great Britain during World War II. Many do not know that Churchill held another, more obscure title as Colonel-in-Chief of the 4th Hussar Regiment — a point made in Con Coughlin’s excellent book Churchill’s First War: Young Winston at War with the Afghans. Among other things, Coughlin sheds light on the background behind Churchill’s history and affiliation with the 4th Hussars in his quest to see battle in the Northwest Frontier of India. In doing so, he provides the reader a unique and fascinating account of one of Churchill’s most formative experiences. Anyone hoping to understand Churchill’s conduct and leadership as Prime Minister during World War II should read this book. Coughlin does an excellent job providing the reader insight into Churchill’s thinking as a young man — to include his professional motivations, world outlook, and insatiable appetite for adventure. One major theme of this book is Lieutenant Churchill’s constant and continuous pursuit of glory, which was a primary reason he found himself fighting on the front with the Malakand Field Force in 1897. Churchill himself states that his boyhood dream of “soldiers and war...[and] sensations attendant upon being for the first time under fire” drove his ambitions to earn battlefield glory. Coughlin repeatedly points the reader to yet another theme in the book, which is that Churchill’s pursuit of glory was rooted in a larger aim to ascend the political ladder in London. Despite these loftier goals of political power, Coughlin ensures that the reader understands Churchill’s knack for soldiering. The author masterfully tells the story of Churchill’s road to enter the ranks of the Malakand Field Force and underscores his reputation as a “very smart cavalry officer” who possessed a renowned “enthusiasm for field work.” Most notably, this book highlights Churchill’s bravery in what was brutal warfare against Pashtun tribes in 1897. Indeed, the reader will learn of Churchill’s carnal desire to kill during battles in the Mohmand Valley, located in what is today the highly contentious border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. These examples are among several in what is Coughlin’s larger purpose of giving the reader extraordinary insight into Churchill as a Soldier and leader — an effort in which the author succeeds in accomplishing.

While Churchill was brave and proficient in the field, the reader will no doubt conclude that he was not a very good counterinsurgent during a conflict that required those principles to be practiced. His belief in British superiority is manifest throughout the book, as is his dislike of British political officers and the mullahs with whom they were charged to negotiate with. In what is one of a series of powerful parallels to modern day counterinsurgency, Coughlin describes a British project to build a major road into a critical base camp, thereby creating a key line of communication and ensuring the ability to spread “the values of the empire.” Opponents of the road argued that it would agitate local tribes and “inflame anti-British feelings on the frontier,” but Churchill was firm in his support for the road project. The project moved forward and is noted as a critical factor that led to the rebellion against British forces along the Northwest Frontier.

Perhaps Coughlin’s greatest achievements in this book are the parallels that he draws with NATO’s current conflict in Afghanistan. Coughlin provides ample discussion of terrain and notes that the Royal Imperial Army lost numerous lives in what we know today as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and Swat Valley — a point not lost on the reader given current events in the region. Coughlin also highlights the fact that the Malakand Field Force largely entered conflict with local tribes because both sides misread the other’s goals and objectives, a point that any modern-day counterinsurgent will appreciate. Moreover, the Malakand Field Force’s misunderstanding of tribal dynamics and its proclivity to hide behind large fortresses parallel two major lessons learned from today’s military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. These concepts come as no surprise to students of modern warfare given the U.S. military’s recent counterinsurgency efforts on the battlefield; however, Coughlin’s work draws attention to the maxim that history repeats itself and should therefore be understood and applied whenever possible.

The title of Coughlin’s book may mislead readers into thinking they will be solely treated to an account of Churchill’s exploits in battle as a young officer. In fact, the author covers a range of topics beyond the battlefield that keep the book both interesting and relevant. Coughlin gives a unique perspective on subjects such as British foreign policy at the turn of the century and journalistic efforts to report the war, and does so in a way that bolsters the larger narrative of Churchill as a soldier. To be sure, Coughlin’s book is not without its faults. Many more pages are devoted to details aside from Churchill’s personal conduct in war that may lead the reader to question the overall purpose of the book. Furthermore, Coughlin only scratches the surface in his analysis of some of the parallels to modern warfare, and often generalizes Churchill’s experience with those of today’s military forces. Yet on balance, the author provides the reader a unique, detailed, and entertaining account of one of history’s greatest leaders and the environment in which he first experienced the exhilaration of combat.

Towards the end of the book, GEN David Petraeus is quoted as saying “What they [British Forces in 1897] did was not something you could do today...They undertook what we would call today a scorched earth policy.” At the same time however, Coughlin notes that Petraeus studied the lessons of the British experience in 1897 prior to assuming command in Afghanistan in 2010 given the many similarities with NATO’s effort in Afghanistan at the time. In Churchill’s First War, Coughlin deftly weaves the life of Churchill into a larger story of warfare, and in doing so underscores these striking similarities. Any student of Churchill, military history, or modern warfare would do well to read Con Coughlin’s fascinating account of one of history’s greatest leaders.

The Only War We Had: A Platoon Leader’s Journal of Vietnam

By Michael Lee Lanning

College Station, TX:

Texas A&M Press, 2007 (reprint), 293 pages

Vietnam, 1969-1970: A Company Commander’s Journal

By Michael Lee Lanning

College Station, TX:

Texas A&M Press, 2007 (reprint), 320 pages

Reviewed by LTC (Retired)

Rick Baillergeon

As a young Infantry officer (many years ago), I seemingly received advice from everyone. One recommendation was from a senior officer who provided me a list of books he said I must read. Topping that list were two books by Michael Lee Lanning entitled The Only War We Had: A Platoon Leader’s Journal of Vietnam and Vietnam, 1969-1970: A Company Commander’s Journal. He said these books would provide me an honest depiction of company-grade combat leadership. As my career progressed, this was counsel I was glad I heeded.

Before discussing the many merits of these books, the story of how the volumes came to print is an intriguing one. Before Lanning deployed to Vietnam, he was advised by his brother (who had just returned from Vietnam after commanding an Infantry company) to keep a journal of his experiences. After initially scoffing at his brother’s suggestion, he later purchased some journals and annotated daily during his time in Vietnam from April 1969 to April 1970. It was a tour highlighted by his service as an Infantry platoon leader, a recon platoon leader, and an Infantry company commander (incredibly as a 23-year old first lieutenant).

When Lanning returned from Vietnam, he let his wife and father read the journals and then packed them away. In 1984, Lanning visited the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial and was greatly moved by the experience. Upon his return home, he dug out the journals, read them, and believed they would provide an understanding of Vietnam War through the eyes of a combat Infantrymen. Lanning discovered he had far too much material for one book and determined two books were necessary. In 1987, he released The Only War We Had which focused on his first six months in Vietnam as a rifle and recon platoon leader. The following year, he released A Company Commander’s Journal which addressed the last six months of his tour. These books were both reissued in 2007 in hopes that a new generation would discover them.

The first thing readers will notice about these books is their organization. Rightfully so, Lanning has organized the book into daily sections. He begins the section with the daily journal entry just as he wrote it in 1969-1970. These are generally short sentences that highlight what occurred in the day for Lanning and the units he led. Following this, Lanning expands on his thoughts after 15 years of retrospection. This expanded discussion may be as short as a paragraph or two or extend to three to four pages.

This period of reflection results in books which inevitably were therapeutic and immensely beneficial to Lanning. They are also books which readers will find extremely powerful. Lanning questions decisions he made and just as importantly, ones that he didn’t make. He addresses opinions and thoughts he had as a lieutenant which over 15 years dramatically changed. The binding tie of this reflection and hindsight is the brutal honesty that is displayed throughout each book.

No one would categorize the Lanning books as polished volumes. There are no glossy color photographs; in fact, neither book contains a single photograph. It is also readily apparent that these books did not go through an excruciating editing process. What a reader simply gets is the words and thoughts of a young Infantry lieutenant leading Soldiers in combat in Vietnam.

Within these words, Lanning addresses the highly emotional areas and challenging situations that a Soldier faced daily in Vietnam. These include dealing with the many aspects of fear. Obviously, the fear of personal death or severe injury comes to the forefront, but also the fear of losing a buddy, the fear of the unknown, and interestingly, the fear of boredom. Within the journals, he also speaks on subjects such as the GI rumor mill, the one-year tour, and the disillusionment many had with the support from the homefront.

Lanning also discusses subjects that were pertinent to him personally. These include his tactical decision-making process, his thought process in dealing with issues with the Soldiers he led, and his challenges with understanding the culture. What is most interesting is the dichotomy of how at the same time he has this mentality to kill his enemy, he is waiting impatiently for the birth of his daughter in the States. This struggle between life and death is a continuing theme throughout the two volumes.

What is the value of Lanning’s books today? I believe their significance lies in several areas. First, for the general public it provides an excellent “foxhole” perspective of the Vietnam War. With most new volumes on the Vietnam War focused at the strategic or political level, this is an area that is now overlooked. Second, despite the numerous company-level memoirs focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, these volumes will still greatly benefit officers and NCOs at the company level. They are filled with numerous lessons learned that are just as applicable today as they were well over 40 years ago.

It had been more than 25 years since I had read the Lanning volumes. I quickly found that the books were every bit as gripping today as they were then. As I completed the books, I thought back to that recommendation I received many years ago. It is advice I unequivocally pass on today. These books unquestionably provide an honest depiction of company-grade leadership. As an added benefit, they provide a snapshot of the Vietnam War taken at a level that is neglected today in Vietnam War scholarship.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print