The Leadership Imperative: A Case Study in Mission Command

by CPT Thomas E. Meyer

Soldiers with A Company, 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division, execute a deliberate attack of an enemy objective during a training exercise. (Photo by 2nd BCT, 101st Airborne Division)

As we transition from more than a decade of war to garrison training, we must identify and implement mission command (MC) into our fighting formations and training management in order to respond to a complex and evolving security threat. Through grounded experiences at the tactical level and academic study of organizational leadership theory, I seek to connect academic theory to Army doctrine and show the successes of MC in practice through a case study of the 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). The following issues discussed are from the point of view and perspective of an individual who has served under multiple chains of command in the positions of platoon leader, company executive officer, and company commander between May 2010 and April 2013.

Hypothetical Vignette

Afghanistan, Regional Command-South — As the battalion conducts air assault operations behind insurgent improvised explosive device (IED) belts, leaders are faced with an ambiguous and evolving operational environment (OE). The commanders of two companies within the battalion execute simultaneous operations, controlling their platoon leaders and maneuvering their units at the order of the battalion commander. A synchronized battalion operation combining assets from air assault capabilities to air-to-ground integration (AGI) is ongoing as companies push south of the primary insurgent IED belts and defensive zones, all driven by detailed command. The company conducting the battalion’s decisive operation pushes south and clears through enemy disruption zones, able to find, fix, and finish the enemy. These two company commanders now face the exploitation phase of their operation but are “off the page” — moving beyond the initial contact and explicit direction provided by the battalion operations order. Instead of understanding commander’s intent, seizing the initiative, and exploiting the initiative (which leads to assessment and dissemination of gathered intelligence), these company commanders are hindered by the micromanagement of the command and control philosophy that results in detailed command.

The battalion ceases operations, and the companies strong-point their locations so these two company commanders can meet with the battalion commander and S3 operations officer. While company leadership is unable to perceive and execute the next step, platoon leaders are stifled and, as micromanaged cogs in the wheel, move with their respective company commanders back to the battalion command post (CP) to receive further detailed guidance. At the battalion CP, platoon leaders gather around imagery of the OE as the S3 and battalion commander brief the scheme of maneuver for this unexpected phase of the operation. As the S3 describes the scheme down to platoon movement techniques, company commanders stand behind their platoon leaders observing the concept of the operation in “receive mode” as they conceptualize the directed concept.

Following the brief, company commanders and platoon leaders move back to their individual locations and prepare to exploit their gains. This process gave the enemy 12 hours to consolidate and reorganize. Following the battalion-directed scheme of maneuver, the platoon leaders depart in the early morning hours and face an enemy, previously broken, in prepared defensive positions protected by various IEDs. Meanwhile, company commanders act as radio operators, relaying information to battalion while awaiting further guidance to maneuver their elements. The lack of MC in this situation created a unit devoid of shared understanding. In failing to know the expanded purpose of the operation, the commanders’ ability to seize the initiative was limited, which allowed the insurgent force to consolidate forces, plan a counteroffensive, and emplace IEDs forward of coalition forces.

“Leadership is […] influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization.” — Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 6-22, Army Leadership

Despite recognizable shortcomings, the kandak possessed many redeeming qualities. First, many of the men were tenacious fighters. They did not shirk from a fight. Afghan hesitation for unilateral actions came from reasonable misgivings about insufficient indirect fire support. Many ANA platoons had been together for three years and endured fierce fighting in Nangarhar, Kunar, and Nuristan provinces. They wanted to do well, and we quickly developed strong relationships at all levels. As we fought and patrolled together, our mutual trust grew.

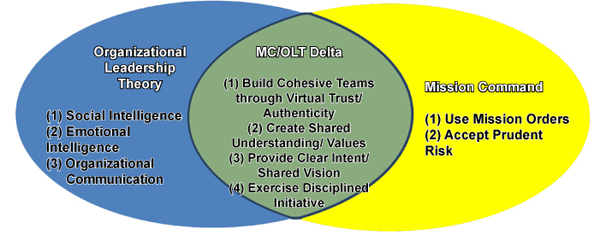

Through the MC Army Functional Concept (AFC), the U.S. Army connects organizational leadership theory to the modern Army Operational Concept (AOC).1 The Army’s six principles of MC act as a system of ligaments connecting the art with science and relating doctrine to current academic leadership theory.2 In an evolving strategic environment, adaptive leadership is critical. The MC AFC connects doctrinal thought to current organizational leadership theory, incorporating the foundations of servant leadership, authenticity, communication, and leader development to maximize human capital and build adaptive leaders at all levels. The above vignette shows the shortcomings faced when detailed command is used in combat rather than MC. However, MC is not readily implemented in combat unless trained and developed in garrison. Through a case study of the 2nd Battalion (Strike Force), 502nd Infantry Regiment, the tenets of MC are married to the foundations of Organizational Leadership Theory (OLT), creating a delta that provides techniques for leadership to succeed in our learning organization (Figure 1).

MC and OLT Defined

In the contemporary operational environment — where ambiguity, change, and uncertainty are ever-present factors — our military leaders are required to provide authentic and credible influence to facilitate revitalization.3 To stay ahead of our enemies, the U.S. Army requires leaders who are perceptive in the art of proactive change in order to build learning organizations and maintain flexibility both in training and on the battlefield. Proactive change is a cornerstone of a learning organization and is the result of an identified glide path with well-known, attainable organizational goals (a “way ahead” or a “vision”) and self-reflection used to gain advantage from new ways of thinking.4 The key to proactive change is creating a culture of continual growth starting at the individual Soldier level.5 The unit shown in the hypothetical vignette failed to understand the process and as such achieved the first three phases of F3EAD (find, fix, finish, exploit, analyze, and disseminate). But, without decentralized and disciplined initiative bred through MC, the hypothetical unit lost the opportunities that Strike Force and units embracing MC achieve — the exploit, analyze, and disseminate portions. In the U.S. Army, officers influence this process, but buy-in is required from the NCO corps and junior Soldiers to sustain growth. To implement OLT in our current fighting formations, the U.S. Army replaced command and control, as a warfighting function, with mission command.

OLT is a combination of ideas and academic theories, proposed and practiced by scholars, which have been tested and allowed into the academic canon. Organizational leadership is the combination of leadership art with the science of management, combining beliefs and management tools to maximize human capital. There is no one doctrine of set rules or beliefs for OLT, but more than a century of academic thought provides a canon of accepted principles to define the tenets of OLT. For the purposes of this analysis, OLT is defined by the primary principles of building teams through authenticity, shared vision, shared values, decentralization to promote initiative, social intelligence (SI), emotional intelligence (EI), organizational communication, and building learning organizations.

MC allows leaders and commanders at all levels to synchronize their capabilities and assets to adapt and overcome all obstacles and enemies; MC doctrine — developed and issued in 2012 — is the basis for unified land operations (ULO).6 ADRP 6-0, Mission Command, defines MC as “the exercise of authority and direction by the commander using mission orders to enable disciplined initiative within the commander’s intent to empower agile and adaptive leaders in the conduct of unified land operations.” MC incorporates a level of art often neglected by the practice-oriented science of its definition. The full spectrum intent of MC is defined in its six-principle framework:

- Build cohesive teams through mutual trust;

- Create shared understanding;

- Provide a clear commander’s intent;

- Exercise disciplined initiative;

- Use mission orders; and

- Accept prudent risk.

These six principles are linked to decades of OLT and provide a framework for building an adaptive, disciplined, and successful unit both in training and in combat.

The Strike Force battalion provides the example of what OLT and MC can create when correctly implemented in combat, as highlighted by recent articles such as the discussion of Operation Dragon Strike during Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) 10-11.7 However, the foundation of MC is not built and implemented in combat but rather starts back in the training environment and is later capitalized upon in combat. If MC had been implemented in the hypothetical vignette, commanders, leaders, and Soldiers at all levels of the organization could have retained the initiative and exploited it without the delay caused by required future guidance from higher. The MC/ OLT delta (see Figure 2), as shown through the actions of the Strike Force battalion, provides a map to how MC can be implemented in garrison at the battalion level and below.

Build Cohesive Teams through Mutual Trust: Authentic Leadership

Authenticity and genuine concern are paramount, and provide the first delta or common ground between MC and OLT. U.S. Marine Corps Col B.P. McCoy prefaces his book, The Passion of Command - The Moral Imperative of Leadership, with this warning: “Without genuine concern, this is all worthless,” and that commanders are entrusted with the safety and welfare of their men. This moral imperative starts in MC with building the team through a mutual trust only attainable, as argued through OLT, by authentic leadership.

The fundamental state of leadership requires an understanding of people, more specifically in this case, of one’s unit from the lowest private to the higher chain of command.8 Without understanding, our leaders lack authenticity and fail to gain trust, thus making mentorship unattainable. MC charges leaders to internalize this fundamental state and moral imperative to understand their subordinates’ motivations, strengths, and areas of needed improvement to allow for specified training needs, positions of responsibility, and individual development, ultimately resulting in an ability to accomplish the mission. The five touchstones of authentic leadership:

- Know yourself authentically,

- Listen authentically,

- Express authentically,

- Appreciate authentically, and

- Serve authentically from OLT aid in the practice and application of MC.9

Authentic leadership — built on a foundation of shared values, perceived motivations, and congruent actions — facilitates trust and creates aligned systems empowering subordinate leaders/Soldiers and in-turn improving the organization. Authenticity is a quality of being “real” and “honest” in how we live and work with others, “rebuilding the links that connect people.”10 Strike Force leaders use trust to build teams by enlisting Soldiers and subordinate leaders to buy-in and adopt the organizational goal as the cornerstone and foundation of their work ethic; understanding this requires a relationship of trust.11 Building this trust relies on the strategic alignment of values, principles, and the organizational mission.12 Strike Force exemplifies the importance of an organizational mission by communicating it down to the lowest level. Strike Force Soldiers, through the principles of MC, are considered subordinate leaders in the framework of the organization and required to understand the unit lines of effort (LOEs), mission, and intent. This facilitates ownership and creates a committed unit, unified by common goals, where trust, commitment, credibility, and accountability gain individual Soldier buy-in.13

Strike Force used open dialogue as a form of strategic internal communication to provide diverse perspectives and develop a culture of learning within the organization. To further promote buy-in and build effective teams, Strike Force created working groups for various mission essential initiatives that enlisted the participation of all ranks. The Fierce Falcon Working Group spearheaded the PT program for the battalion and infused change to improve Soldier comprehensive fitness. The mission of the working group was to gain a comprehensive voice from all levels within the battalion to improve a program dedicated to optimizing the physical and mental development and sustainment of the battalion’s most lethal weapon.

Members from each company, varying from rifleman to the battalion commander, received an equal voice unhindered by rank or formal duty position. To achieve this, formally assigned leaders needed to be confident in their message and accept risk in the vulnerability that comes from giving equal voice to those usually on the receiving end of orders.14 The vulnerability and control sacrificed paid dividends in the buy-in received. Officers within a battalion are more apt to switch-out as part of the Army’s revolving door of personnel, but the NCOs and Soldiers are the consistency of the unit, and when they take ownership of the vision, the effects last. Subordinate leaders’ level of commitment and work ethic skyrocket when they have a say in the organization. Through its Fierce Falcon PT Program (driven by its working group), Strike Force witnessed improvements in comprehensive fitness including an average of more than a 50-point improvement in Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) scores and improved combat fitness test scores. This collection of diverse opinions harnessed creative tension and provided answers by developing creative and critically thinking leaders.15 The obvious returns on this program and working group are shown through quantitative data on Soldier fitness and combat readiness. However, the less visible return is the implementation of MC through shared vision and ownership, which combats the need for detailed command displayed in the initial vignette and creates leaders ready to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative as guided by commander’s intent. This theory of tapping into human capital, gaining initiative by sacrificing control, is at the cornerstone of servant leadership and MC.16

Strike Force exemplified servant leadership, and through the overlap between OLT and MC, built cohesive teams through the execution of command climate surveys, safety briefs, and the Family Readiness Group (FRG) program. Command climate surveys are not unique to Strike Force, but how the battalion executed and implemented them is what truly exemplifies the MC/OLT delta. Strike Force did not treat command climate surveys as a “check the box” exercise but, rather, valued them as an opportunity to check the pulse of the unit and allow candid feedback at all levels. Following the survey, a selected group of leaders from multiple levels (squad leaders, platoon leaders, etc.) analyzed the answers/responses and recorded them into an easily transferable format determined by the battalion commander and his staff to best communicate trends across the battalion. Data provided to the commanders portrayed a statistical picture of certain metrics or majority responses while still capturing the outliers. Following a week to allow commanders to digest this information, companies held sensing sessions for each level of their organization (Soldiers, team leaders, squad leaders, and then platoon leaders/platoon sergeants). The battalion command team repeated the same process including all companies to ensure a comprehensive opportunity to gain/voice feedback. Face-to-face communication between commanders and all levels of their subordinates facilitates a measure of respect and weight to their feedback. This simple practice shows subordinates they have a say in the organization and that their voice matters. The returns on this investment are difficult to gauge through quantitative means but are reflected through the human element of leading.

Leaders at all levels of the battalion, especially commanders and first sergeants, used safety briefs as a form of open dialogue between the formal leadership and the Soldiers to create a relationship of mindful communication and equitable transactions.17 In the Strike Force culture, safety briefs were not a one-way lecture from commander to Soldier. They were treated as group communication between all Soldiers and leaders, where multiple individuals had the opportunity to talk about each subject of necessary attention. Giving Soldiers the opportunity to talk to their peers and leaders about the dangers of drugs and required safety measures for drinking alcohol, hunting, or riding a motorcycle facilitated active participation and helped the message sink in. During this time, Soldiers were more apt to receive a message from their command team because it was received as authentic communication rather than robotic lecturing. This provided leaders with the opportunity to convey the right message at that critical moment to reach and develop their subordinates. These interactions became training opportunities to build a cohesive team rather than just a safety brief requirement. The better Soldiers understand the values and vision of their organization in garrison, the less they will require the detailed command and micromanaged supervision that limited our hypothetical unit highlighted in the vignette.

“Friendship” with subordinates holds a negative stigma within the Army that leads to a failing of leaders to understand and know their Soldiers and junior leaders. A fine line exists between professional understanding and unprofessional interactions. The leaders in Strike Force understood the line between professional behavior and hiding behind excuses about avoiding friendships with colleagues to not get “too close.” The battalion’s leaders viewed their relationships with Soldiers as a family to avoid portraying a “lack of candor or fail to validate emotions.”18 This attitude permeated unit gatherings both at work and outside of work, such as FRG meetings and socials that allowed individual Soldier family units to congregate and build the larger support structure within the unit. The battalion commander frequently (twice a month) held volunteer weekend workouts at his house on Saturdays. These gatherings were open to all ranks/positions and advertised throughout the battalion area. Soldiers, leaders, spouses, and children gathered at the battalion commander’s house to participate in tough and meticulously programmed PT sessions, followed by a family-style breakfast. These opportunities to gather as colleagues, build bonds through strenuous physical activity, and break bread as family helped to build the bonds of a cohesive unit that pay off on the battlefield. Leaders who fail to do this mistake the dangers of institutional vulnerability as transferable to personal vulnerability through genuine expression and transparency.19

Strike Force united MC’s building cohesive teams to OLT’s authentic leadership through open communication between leaders and subordinates in the form of dialogue, thus creating a foundation of mutual trust. The U.S. Army requires counseling, but where Strike Force achieved the further intent of MC is in how they counseled. Leaders mentored their subordinates and used every training opportunity as a form of open dialogue to counsel. The Army’s DA Form 4856 offers a section devoted to “discussion,” but in an OLT sense, this discussion is dialogue in that it is a process by which meaning is transferred.20 Dialogue is a free flow of meaning between two or more people where information sharing is crucial to achieving understanding.21 Strike Force leaders understood that dialogue is a relationship built over time. Every range, physical training session, and even command maintenance Mondays were viewed as opportunities to engage subordinate leaders and instill knowledge through communication as a form of building authentic relationships through trust. No leader in battalion exemplified this as well as the Strike Force team leader.

Team leaders are the lowest level of recognized Army leadership. However, even the team leader viewed his Soldiers as subordinate leaders because he understood he was not only training his SAW gunner or grenadier, he was training his own replacement. Authentic communication guides leaders by fundamental values and a foundation of character, allowing flexibility in their methods to reach every individual; one-size-fits-all leadership is not nearly as effective.22 Above all else, authentic leadership starts at the top and requires shared values and vision to ensure congruent action.23 The Strike Force battalion formed a cohesive team through authentic leadership and mutual trust but executed initiative as a team through shared understanding. This shared understanding in training will later correlate to understanding in the mission and avoid the failings of detailed command in combat as shown in the vignette.

Create Shared Understanding: Values

Shared understanding is the bridge that connects purpose and intent, ensuring subordinate leaders and Soldiers to the lowest level are able to operate within that intent.24 The delta between shared understanding (MC) and OLT is shared values. Values and ethical stewardship display authenticity and achieve a fundamental state of leadership, facilitated by MC and aligned with the values of servant/principle-centered leadership.25 Through aligned systems such as counseling, safety briefs, and officer/leader development programs (ODP/LDPs), Strike Force leaders acted as ethical stewards and conveyed a clear message using strategic communication, effectively guiding and mobilizing personnel toward a common mission. Battalion Soldiers communicated this through actions and words to connect common organizational values at the individual level as the shared understanding of MC. Strike Force leaders created an environment and culture of family, exemplifying through actions the belief that “we all work for each other.” Strike Force leaders dedicated “personal time” to ensuring their Soldiers and subordinate leaders were cared for, showing that their priority was to their Soldiers and thus building a commitment to the unit. Examples of this were displayed through individual and collaborative leader efforts. On the individual front, specific examples include a squad leader dedicating weekends to teaching a Soldier to drive and walking him through the process of attaining his driver’s license. Collaboratively, Strike Force implemented home visits that required leaders to visit the quarters (both on post and off) of every Soldier, NCO, and officer within the organization to ensure families were being taken care of, information was effectively being disseminated to the family, and the individual was living in a safe environment. These were conducted as a means of ensuring a Soldier’s standard of living was acceptable to his needs and the needs of his family. This also provided an opportunity for leaders to conduct face-to-face communication with family members who may not attend FRG meetings/functions and/or as a check on the lines of communication.

Another accepted and practiced SOP in Strike Force was for leaders to arrive early to morning formation to conduct barracks checks; they would also take turns to do these on weekends as well. These checks were not conducted as “witch hunts” or to catch wrongdoing, but rather to show that leaders care enough to take time out of their weekend to walk through their Soldiers’ living space and ensure their needs are met. Leaders use these and other methods to keep a finger on the metaphorical pulse of the organization and show they value each Soldier as a member of the family unit. New Soldiers and leaders are quickly inculcated to keep the organization at a consistently moving pace, united by a common bond.

GEN (Retired) Gordon R. Sullivan, former Army Chief of Staff, relates strategic alignment and architecture to a bridge with values as the foundation and aligned strategy as the connection between values and means.26 This alignment starts with the congruence of espoused values and culture or “lead by example/through action.”27 Just as leaders achieve authenticity through clearly defined personal motivations, core beliefs, and fundamental values, organizations/units require these baselines to act congruently within them.28

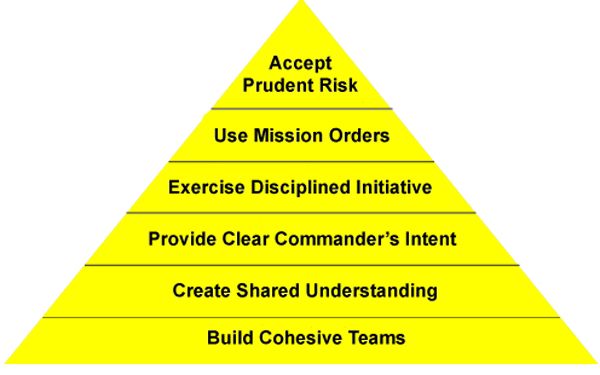

The principles of MC act as this strategic framework (Figure 3), building the foundation with cohesive teams and then infusing shared understanding to continue the building process toward the pinnacle of allowing leaders to accept prudent risk and ultimately creating an adaptive learning organization. Strike Force’s leaders were not genetically altered or specifically better than any other leader in the Army. Instead, Strike Force took the next step by approaching every task as a training opportunity, planning and executing deliberate multi-echelon training to maximize resources. Instilling this as a cultural understanding and core value of the organization created that baseline and set expectations. Daily PT is not executed solely to maintain standards of fitness, but rather as part of a larger strategic plan to build/foster shared understanding and create adaptive leaders. The Fierce Falcon PT Program assisted in creating a culture of physical, mental, and emotional resilience shown through moral, physical, and adaptive courage. The program was approached with diligent attention from the working group, and all commanders intentionally planned fitness modules and programming that would challenge leaders, promote esprit de corps, and improve comprehensive fitness. Results of the program (APFT scores, functional movement screening tests, combat fitness test scores, etc.) were reviewed and the next phases of programming were briefed to the battalion commander at quarterly PT meetings. LDPs on fitness, nutrition, and other related topics were spearheaded by individual companies and taught to the battalion as a whole. Fierce Falcon was designed to transform Soldiers and leaders into standard-bearers, build unity, and instill adaptive courage through physical training. The Fierce Falcon program meant training for, achieving, and maintaining a level of comprehensive fitness gauged by the Fierce Falcon metrics of success (various tests to include a 12-mile ruck march, APFT, five-mile run, combat fitness test, and comprehensive fitness test).

Creating and building on mutual experiences — whether it is through PT, FRG functions, or strenuous field training — instilled a shared understanding at all levels of the organization. This understanding was facilitated by OLT’s proposed need for common core values of the organization, commonly identified within the individuals. Shared understanding, within the framework of MC, creates a platform on which to instill shared vision/commander’s intent.

Provide a Clear Commander’s Intent: Explain the “Why” through Shared Vision

Shared vision is the fourth discipline of a learning organization within OLT and essentially the third principle of mission command.29 Genuine vision instills a “want” to learn or “common caring” rather than a directive.30 Vision fails to breed initiative when kept as a leader’s secret. For vision to take effect, it must be communicated, understood, and shared by the organization. Vision, as it is displayed in the MC Strategic Framework, needs to be based on common principles in order to achieve a lasting effect.31 Commander’s intent, when implemented to achieve the above discussed requirements, allows subordinate leaders and Soldiers to “fight on to the Ranger objective and complete the mission though [they] be the lone survivor.” A clear end-state with benchmarks for success facilitates a better understanding of change in both the “how” and the “why.” When the “why” is understood, leaders can adapt the “how.”

Before the OEF 12 Strike Force Security Force Advise and Assist Team (SFAAT) deployed, the senior leaders deploying set expectations by providing a vision that guided the organization. The published and understood leader expectations created a culture of self-responsibility and egalitarianism (the message and vision comes from the top).32 A decentralized style of empowering subordinate leaders, driven by a strong and understood vision, allowed for a more effective span of control.33 This was not to say leaders were not required but rather emphasized the freedom to seize initiative and execute within the leader’s communicated vision. Not only was the vision and guidance published by the battalion commander, it was also discussed and implemented at all levels of the organization (short-range training calendar, long-range training calendar, mission essential task list evaluations, Road to War operation order) to describe the way ahead and leader expectations. Leaders from every level of the organization often approached Soldiers and asked for the “why.” (Why are they training? What is the task? What is the purpose of the organization?) Soldiers were expected to have these answers because leaders were expected to provide and instill them. Leaders understood Soldiers will not always do what you expect them to do, but they will always execute what you inspect. When the vision is not only communicated but also documented and inspected for understanding at every level, leaders can refer back to it as a map through turbulent times.

When Soldiers, NCOs, and junior officers “buy into” the vision, they — like any shareholder — want their piece. Soldiers will then take ownership, provide input, seek collaborative thought, and accomplish effective change to create a guiding coalition without a second thought or understanding of what they are doing. The art of MC allows commanders to tap into the human capital provided by Soldiers and junior officers, well beyond their own individual expectations or comprehension. With collaborative initiatives, Soldiers feel personal gratification and satisfaction when yielding positive results.34 Once the guiding coalition is created and the team is built around a common vision, strategies can be discussed, developed, and exploited. It is the leader’s responsibility to find what motivates his Soldiers and subordinate leaders and use that to involve them.35

Once vision is created and communicated, the thought needs muscle; a good manager provides the muscle through strategies. The Army has a command structure that pairs managers (executive officer [XO], first sergeant, S3, etc.) with leaders (commanders) to provide the “muscle” or the “how” behind the “thought” or vision/why. Strike Force understood and exemplified this relationship and ensured managers were on the same page with the leaders to execute vision within an understood intent. Through this symbiotic relationship, Strike Force leaders demonstrated the power of providing a clear commander’s intent (vision) through the connection to and ownership of the organization at all levels. Understood intent, or vision, distributes the authority to act with initiative to every individual in the organization. When this is implemented and instilled through training, the initiative gains a strengthened resolve through discipline. A unit able to exercise disciplined initiative, as outlined in MC and OLT, avoids the detriments of detailed command outlined in the initial vignette. By communicating the shared vision (or commander’s intent) across all levels of the organization, Strike Force built on the foundation already present in its cohesive teams and shared values, thus allowing for the next step in the process: exercising disciplined initiative.

Exercise Disciplined Initiative: Succession Planning, Mentoring, and Diverse Perspectives

Complacency kills learning organizations, and comfort breeds complacency. Maintaining relevance in an organization’s field, national, and global communities is the crux of continuous success. Leaders hold a critical charge and monumental challenge to breed continuous hunger within their organizations. Strike Force bred this hunger through strategic succession planning and leader placement. The key to proactive change is creating a culture of continual growth, starting at the individual level, that is nurtured by organizational leaders driven by the ability to exercise disciplined initiative.36 Three principles already discussed breed disciplined initiative: build cohesive teams, create shared understanding, and provide clear commander’s intent. Putting these into practice to seize, retain, and exploit initiative is accomplished through succession planning, mentorship, and diverse perspectives. In order to influence and impact a lifelong learning organization, leaders need to be able to reach the pinnacle and strive for more; leaders need to ask “what’s next?”

Strike Force, as part of the larger strategic scheme of the Army, rotated leaders within the organization to keep the hunger, drive, and determination required to meet the growing challenges of our national security and answer the call of the changing environment. The battalion demonstrated the power of mentorship, incorporating consent, mutual respect, and proven excellence through the mantra of “leader development” to effectively develop succession planning and maximize human capital. Organizationally in-tune leaders understand that maximizing human capital and building profits from people are not solely based on short-term earnings. The true Human Capital Management (HCM) model understands that “hope is not a method” and integrates succession planning, a form of deliberate planning for filling voids left by leadership’s revolving door for long-term success.37

Organizational Leadership Theory’s HCM is a people-centric approach with all functions and factors of the organization feeding into investing in people. HCM requires the application of organizational strategic systems to develop employees and build profits from people.38 The disciplines of learning organizations to building an HCM are decentralization, self-managed teams, selective hiring, employee training and development, shared decision-making, transparency, and performance-based incentives.39 The HCM is creating a learning environment through leader development using coaching and mentorship as a catalyst for improvement.

Doctrine dictates that leaders understand the position and responsibilities two levels above their own. For example, a squad leader understands decisions at a first sergeant (company) level, and a company commander understands the position of a brigade commander. Realistically, leaders understand two levels up and are prepared to execute one level up. Strike Force planned and executed training/knowledge management (KM) in a fashion that exemplifies this doctrinal charge to leaders.

From February 2012 to January 2013, the Strike Brigade deployed 90 percent of its leaders (officers and senior NCOs) to form an SFAAT charged with training Afghan Uniformed Police, National Police, and Afghan National Army in the staff functions and training management techniques required to sustain their own national security. Meanwhile, the remainder of the brigade stayed at Fort Campbell fully engaged in an intensive training cycle (ITC) that was challenging to even the most prepared and distinguished leaders. This required executive officers to step up and execute as company commanders (battalion XO to act as battalion commander). At all levels, leaders were working one to two levels above their rank/grade.

XOs manage systems rather than directly command people. However, managing people, talent, personalities, etc., are critical factors in being an XO. Attack Company fostered a mentorship relationship between the commander and XO based on trust and mutual respect. This relationship prepared the XO to seamlessly step into the commander billet where he already understood all of the systems and requirements. As part of a deliberate leader development/mentorship strategy, the Attack Company commander included his XO in the planning process and training management discussion. He then placed his XO in positions to operate as the commander (battalion training meetings, sync meetings, quarterly PT briefs, etc.). When word of the deployment broke, Attack Company was levels above the rest of the brigade in terms of preparation to shift the organization. Attack Company’s ability to understand the system and build succession planning into training/leader development allowed for organizational learning and adaptability; it allowed leaders at all levels to exercise disciplined initiative.

Leaders plan, not because execution always follows suit, but because the planning allows for adaptation in practice. Competitive organizations understand the revolving door of personnel changeover and preemptively attack this barrier through succession planning with mentorship acting as the catalyst for leader development.40 Succession planning is a cornerstone of effective human capital strategy with an undeniable link to strategic/systematic coaching as a form of management.41 OLT requires a balanced approach to management and leadership through the lens of HCM and KM, providing a link to MC’s disciplined initiative.

Strike Force implemented the principles of transparency, systems consultation, decentralized decision-making authority, shared control, and mentorship. The battalion took advantage of the Army’s structural organization, placing leaders in roles formatted to mentor a specific group. For example, company commanders mentored XOs and platoon leaders while coaching squad leaders. Strike Force aligned to facilitate mentorship one level down and coaching two levels down in accordance with doctrine. When this structural alignment combined with the personal relationship of mutual trust and respect discussed above, mentorship was perfectly facilitated. This structure of mentorship prepared leaders to step up and move into the role of the leader above them. Strike Force displayed this perfectly when required to put succession planning into practice during the OEF 12 SFAAT deployment. When the deployed leaders returned to their formations, the organization was exponentially better prepared to continue training. The subordinate leaders who were trained, coached, and mentored and then charged to lead levels above their assigned position exercised initiative in the absence of higher leaders to drive the organization in the direction of the shared vision/intent. These leaders, when placed in the vignette, were prepared to exercise initiative within the confines of intent and continue the mission without allowing the enemy to consolidate and reorganize.

Conclusion

As deployments and the timeline of leadership change of commands would have it, Strike Force did not deploy as a battalion under these discussed command teams. Nevertheless, the trained foundations of the MC/OLT delta could have given the hypothetical vignette a different outcome.

Hypothetical Vignette Revisited: Afghanistan, Regional Command-South — As the battalion conducts air assault operations behind insurgent IED belts, leaders are faced with an ambiguous and evolving OE. The commanders of two companies within the battalion execute simultaneous operations, controlling their platoon leaders and maneuvering their units at the order of the battalion commander. A synchronized battalion operation is ongoing as companies push south of the primary insurgent IED belts and defensive zones, all driven by detailed command. The company conducting the battalion’s decisive operation pushed south and cleared through enemy disruption zones, able to find, fix, and finish the enemy. These two company commanders now face the exploitation phase of their operation but are “off the page,” moving beyond the initial contact and explicit direction provided by the battalion operations order. By understanding of the commander’s intent, however, commanders and leaders at all levels are able to seize and exploit the initiative, leading to assessment and dissemination of gathered intelligence.

Company commanders, with understanding of the larger battalion effort, strong-point their locations and gather their platoon leaders. As company teams, these leaders plan the next phase of their connected operation with their adjacent units’ tasks and purposes in mind. Commanders then use the battalion update brief conducted via FM communication to brief the battalion commander on their plan. The battalion S3 synchronizes these plans ensuring a united effort. The battalion commander provides additional guidance and allows his company commanders to execute their plans. Once synchronized, company commanders disseminate the plan to their subordinate leaders as their subordinate leaders start necessary movement. Before first light, platoons begin to conduct their continued movement toward the river clearing the last remaining insurgent strongholds and clearing the area of Taliban influence. As the battalion’s clearance operations come to a close, commanders use the guidance they received the night before and their understanding of mission/intent to strong-point strategic locations within the area of operations to facilitate future combat and stability operations. The enemy was kept on his heels and pushed past his brink. Now coalition forces hold the ground allowing for security in the region and a transition to the counterinsurgency operations required to succeed in the human domain.

GEN (Retired) Sullivan relates the Army’s Human Capital Model to empowering subordinates, building a team, creating a strategic architecture, transforming the organization, growing the learning organization, and investing in people.42 The U.S. Army later defined Sullivan’s statements through the restructuring of command and control to the new doctrine of mission command. Through our current transition, we as an organization need to apply MC in our garrison training toward readiness to face an evolving security threat. To tap into the full strength of human capital, our leaders need to recognize the connection between current MC doctrine and OLT as a means of implementing knowledge management to develop and train their formations. Strike Force modeled the principles of MC to reveal the shared delta with OLT and tap into the uses the first hidden power of human capital. This leadership “sweet-spot” created a unit of flexible leaders — from Soldier level to command level — that is able to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.

Notes

1 Richard N. Pedersen, “Mission Command — A Multifaceted Construct,” Small Wars Journal, 17 November 2010, accessed 2 May 2013, http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/mission-command-%E2%80%94-a-multifaceted-construct.

2 Army Doctrine Reference Publication 6-0, Mission Command (2012): 2-1.

3 Kerry A. Bunker, “The Power of Vulnerability in Contemporary Leadership,” Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice And Research 49 (1997): 122.

4 Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (2nd edition) (NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 2006): 40.

5 J. Stewart Black and Hal Gregerson, It Starts With One: Changing Individuals Changes Organizations (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2008).

6 Donald P. Wright, general editor, 16 Cases of Mission Command (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2013): iii.

7 Ibid.

8 Robert E. Quinn, Moments of Greatness: Entering the Fundamental State of Leadership (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2005).

9 Kevin Cashman, Leadership From the Inside Out: Becoming a Leader for Life (Provo, UT: Executive Excellence Publishing, 1998): 120-128.

10 Eric M. Eisenberg, H.L. Goodall, Jr., and Angela Trethewey, Organizational Communication: Balancing Creativity and Constraint (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007): 174.

11 James Kouzes and Barry Posner, The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007): Chapter 6.

12 Jeffrey Pfeffer, The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1998): Chapter 4.

13 Karl Albrecht, Social Intelligence: The New Science of Success Beyond IQ, Beyond IE, Applying Multiple Intelligence Theory to Human Interaction (NY: Jossey-Bass, 2006): Chapter 4.

14 Quinn, Moments of Greatness.

15 Eisenberg, Goodall, and Trethewey, Organizational Communication, 41-44.

16 Cashman, Leadership, 120-128.

17 Eisenberg, Goodall, and Trethewey, Organizational Communication, 41-44.

18 Bunker, “The Power of Vulnerability,”124.

19 Wilfred Dolfsma, John Finch, and Robert McMaster, “Identifying Institutional Vulnerability: The Importance of Language, and System Boundaries,” Journal Of Economic Issues 45-4 (2011): 808.

20 Senge, The Fifth Discipline, ix-xx.

21 Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler, Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High (NY: McGraw Hill, 2012): 23-24.

22 Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (NY: Free Press, 2004): 217.

23 Pfeffer, The Human Equation, Chapter 4.

24 GEN Martin E. Dempsey, “Mission Command,” White Paper, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Washington, D.C., 2012.

25 Quinn, Moments of Greatness.

26 Gordon R. Sullivan, Hope is Not a Method: What Business Leaders Can Learn from America’s Army (NY: Broadway Books, 1997): 99.

27 Pfeffer, The Human Equation, 100.

28 Boyd Clarke and Ron Crossland, The Leader’s Voice: How Your Communication Can Inspire Action and Get Results (NY: Tom Peters Press, 2002): Chapter 1-2.

29 Senge, The Fifth Discipline, 9.

30 Ibid, 191.

31 James C. Collins and Jerry I. Porras, J.I.. Building Your Company’s Vision (Boston: Harvard Business Review, 1996).

32 Kouzes and Posner, The Leadership Challenge.

33 Lorin Woolfe, The Bible on Leadership (NY: Amamcom American Management Association, 2002).

34 Black and Gregerson, It Starts With One.

35 Stephen R. Covey, Principle Centered Leadership (NY: Free Press, 1991).

36 Black and Gregerson, It Starts With One.

37 Sullivan, Hope is Not a Method.

38 Cassandra A. Frangos, “Aligning Human Capital with Business Strategies: Perspectives from Thought Leaders.” Harvard Business Review, 15 May 2002.

39 Pfeffer, The Human Equation.

40 Senge, The Fifth Discipline.

41 D. Kevin Berchelman “Succession Planning,” The Journal for Quality and Participation, 28/3 (2005): 11-12.

42 Sullivan, Hope is Not a Method.

CPT Thomas E. Meyer is currently serving as the assistant operations officer with the 5th Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash. His previous assignments include serving as a platoon leader (12 months in Afghanistan in support of OEF 10-11), company executive officer and company commander in Attack Company, 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Ky. He has bachelor’s degrees in English and History from Norwich University and a master’s degree in Organizational Leadership from Norwich University.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print