Trust: A Decisive Point in COIN Operations

by LTC Aaron A. Bazin

Bravo Company, led by CPT John Smith, has assumed responsibility for a new area of operations in Afghanistan. This area includes a village, which according to intelligence reports, occasionally supports insurgents who conduct improvised explosive device (IED) attacks in the area. During their first week in the new area, a roadside IED attack kills one of the company’s Soldiers and wounds two more. Tensions run high in the company, and Smith develops an aggressive plan to root out insurgents in the village. He back briefs the battalion commander, who approves the plan but directs that they must first meet with the tribal leadership to see if there is any way to gain their support…

Ahmad Khan has lived in the village since he was a boy and is the head of one of the largest and most respected families. Little goes on in the village that he does not know about. He has tried his best to keep the violence outside of his village and prefers to not get involved if he can. However, he is fairly certain that one of the families allows insurgents to store explosives at a safe house somewhere in town. There seems to be many more Americans around recently, and he is concerned that there may be violence in his village soon. An armed convoy approaches his house and a clean-shaven Soldier that looks as young as one of his children approaches. The Soldier introduces himself as Captain John and extends his hand…1

According to Field Manual (FM) 3-24, Counterinsurgency (COIN), the struggle for popular support is often the center of gravity of a COIN operation. The insurgent force requires a supportive or apathetic population to exist. At the same time, the counterinsurgent strives for popular support to help increase legitimacy for the host nation. As such, influencing the will of the people becomes a fundamental military objective for both sides.

As counterinsurgents plan, they can choose to array decisive points along logical lines of operations to achieve their desired ends.2 The decisive point of an operation is a “geographic place, specific key event, critical factor, or function that, when acted upon, allows commanders to gain a marked advantage over an adversary or contribute materially to achieving success.”3 During conventional operations, decisive points are typically enemy locations, which once controlled will lead to a military advantage. For counterinsurgents, identifying these points is not quite as simple as drawing a circle on a map. Arguably, one important decisive point of any long-term COIN operation is trust — the “psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another.”4

Neither CPT Smith nor Ahmad realize it right now, but their meeting today will set the stage for a relationship of trust that will ultimately determine the shared fate of the villagers, Soldiers, and even the insurgents as well. How well they find common ground and resolve shared problems could very well determine which direction the village will turn. They have arrived at a critical decisive point.

Three Potential Outcomes: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

If we play out the best-case scenario, the meeting goes well and the parties find some common ground — a win-win. Let us say that Ahmad gives the company commander some information that leads to the company successfully locating an insurgent safe house. CPT Smith is able to promise some development projects that improve the quality of life in the village and help local forces provide a secure environment. He follows-up on his promises, trust increases on all sides, and everyone gets what they want... Except the insurgents that is, who lose support of the population and a secure location from which to operate. In this scenario, the counterinsurgent gains a marked advantage.

In the worst-case scenario, the parties on both sides deceive each other. Smith promises more than he can deliver or loses his temper and outright threatens Ahmad. Perhaps Ahmad misdirects Smith to the wrong part of town, tips off the insurgents so they can avoid the crackdown, or helps set a trap for the company. In this lose-lose scenario, things only get progressively worse as the company distrusts the people, and the people distrust the company in turn. In the worst-case, no relationship of trust forms; the insurgents retain their sanctuary and can strike with impunity at any time and place of their choosing. Here, the outcome favors the insurgent.

The most probable outcome exists in the murky area somewhere between these two extremes. It is unrealistic to expect one meeting will lead to trust, and at best, the initial outcome is conditional trust. Ahmad postures, attempting to appease and placate both sides, and tries to please whomever he feels has the most to offer at the time. Smith conducts regular meetings and is cautiously optimistic, but he remains ready to drop the hammer if the situation calls for it. In this scenario, the trust outcome is uncertain and neither the insurgent nor the counterinsurgent gains a marked advantage. Only time will tell. As the insurgent will remain long after the counterinsurgent leaves, in the case of a tie, the advantage goes to the insurgent.

These three potential outcomes are an oversimplification of the very complex problems faced by Soldiers in the field but highlight an important point: trust is critical to long-term success. The need for trust takes many forms depending on the stakeholders involved and the nature of the mission. As described here, the counterinsurgent could build trust with local leadership, with military or police partners, or with host-nation military trainees. In recent years, the American military has learned (or perhaps relearned) many lessons of how to build trust to gain advantage over their adversary in a COIN fight.

Components of Trust: Context, Time, and Confidence-building

Through trial and error, service members have learned that COIN and stabilization operations require much more than the biggest stick. For the counterinsurgent, the first critical factor required to build trust is the ability to understand the context of the situation fully. Smith and Ahmad have some big differences between them based on their backgrounds, personal abilities, and the choices they have made in their lives. They were born and raised under very difficult circumstances and have very different perspectives and worldviews. Cultural differences in education systems, religion, symbols, or behavioral norms could impede communication and the development of trust. As such, the counterinsurgent must always be aware of societal and cultural areas of sensitivity.5

If the last American leader that Ahmad interacted with was brash and disrespectful, this may color his perceptions and affect the initial level of trust he feels toward Smith. The level of security in the local area can affect the level of felt distrust as well. In our vignette, the company just lost a Soldier. It is natural to expect that Smith will distrust Ahmad, use caution in discussion, or overreact and display anger. Overall, the ability to understand underlying assumptions, past experiences, and the limiting factors of context will help set the stage for building trust.6

The second critical factor that the counterinsurgent must understand is that it will take time. The time required to build trust can range from a few weeks to six months or more. With focused effort and regular interaction, trust typically forms at around the two- to- three-month mark. If the parties share significant risk, such as high levels of enemy contact, a strong bond of trust can form in a matter of weeks. Overall, counterinsurgents should not expect instant results; they will have to conduct numerous meetings and invest a significant amount of time to build rapport and an enduring bond.7

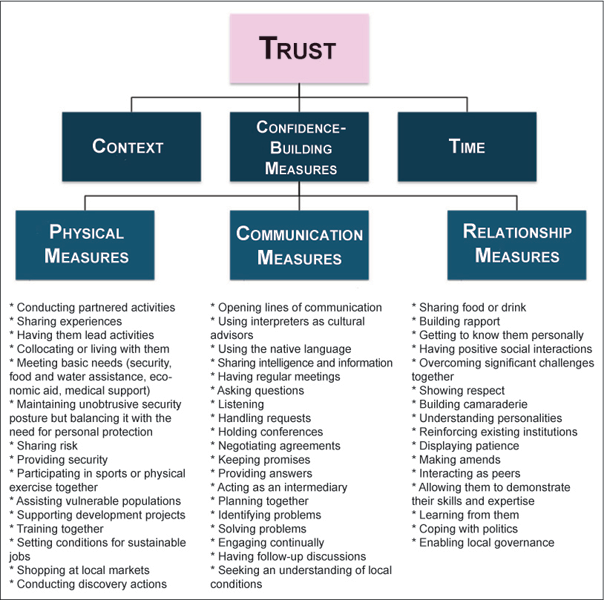

The third critical factor for the counterinsurgent to understand is the use of confidence-building measures. Confidence-building measures are the activities that can bring conflicts closer to positive resolution through of promotion the belief that, in the future, each party will act in a mutually beneficial manner. In COIN operations, confidence-building measures generally fall into the following categories:

- Physical measures,

- Communication measures, and

- Relationship measures.

Physical measures are activities that demonstrate positive intention. Communication measures are activities to exchange information, ideas, and perspectives. Relationship measures are activities that improve interpersonal connections (see Figure 1).8

Types of Confidence-building Measures

Confidence-building measures come in many shapes and sizes, and there are no universal methods for earning the trust of another human being. Physical measures demonstrate positive intention through deeds, not words. One of the easiest but most important things that a counterinsurgent can do to build trust is to collocate with those that they want to build trust with. This leads to shared experiences, risks, and rewards. Through simply being present and involved on a regular basis, the counterinsurgent lays the foundation for trust. To build upon this foundation, the counterinsurgent can conduct partnered activities with the goal of eventually stepping back and supporting the partner in the lead.10

In an environment where the counterinsurgent cannot speak the native language and must communicate through a translator, physical indicators of positive intention go along way. This includes activities such as helping the other stakeholder meet basic human needs (e.g., providing security, food and water assistance, economic aid, medical assistance). As the stakeholder sees the benefit that the counterinsurgent provides over time, they begin to understand the counterinsurgent’s positive intentions.11

Another physical confidence-building measure that coun-terinsurgents commonly use is to display a non-threatening security posture. This can include actions such as simply removing dark sunglasses to make eye contact, removing helmets and body armor, or being careful to carry weapons in a non-aggressive way. Research studies into the psychology of conflict indicate that the visual presence of weapons can significantly increase the likelihood of aggression and violence. This measure can be controversial because the norms of military behavior are to stay in uniform and always be ready for enemy contact. Again, there is no right answer, and Soldiers must apply professional military judgment to determine what is most appropriate for the situation and level of threat.12

The counterinsurgent can use many other actions to communicate trust and gain trust in return. These include activities such as: participating in sports or physical exercise together, assisting vulnerable populations, supporting development projects, training together, setting conditions for sustainable jobs, or shopping at local markets. What is important for the counterinsurgent to remember is that actions can speak louder than words, and what they say must back up what they do.13

Counterinsurgents can conduct a wide variety of activities to improve the exchange of information, ideas, and perspectives. First, for communication to exist, the counterinsurgent should open a line of communication that allows for a free and open exchange of ideas. Language is a natural barrier to communication, and the ability to speak even a few words of the language helps establish rapport. Often, the interpreter becomes the lynchpin, and beyond simply transmitting a message, interpreters act as personal advisors to provide insight into the nuances of culture and the impact of the message the counterinsurgent is sending.14

Meetings should occur regularly and follow societal norms. In many cultures, people prefer to handle business in small groups or one-on-one after social activities. In these cases, large public forums may actually hamper communication.15 The counterinsurgent should tailor the nature and formality of the communication forum to the audience.

Often, American officers approach meetings in a very western business-like manner, with a set of agenda items and decisions they need right now. Instead of listening, out comes the standard issue little green notebook and they recite their pre-written talking points, almost oblivious to the person they are talking to. Almost as ineffective is when the officer goes the other route and defaults to note-taking mode, trying to write down every word the other person says. Again, the little green notebook gets more attention than the person sitting across the table does.

Ideally, the counterinsurgent can find a balance between the two through active listening (maintaining eye contact, paraphrasing, and showing empathy).16 Trust-building communication comes first from listening, then understanding and finding common ground, and then solving problems together. When communicating, the counterinsurgent must resist the urge to jump right to the end and display patience. With patience, small gains over time can build to an irreversible momentum.

The final category of confidence-building measures is relationship activities. These activities are largely social interactions and may or may not be focused directly on the counterinsurgent’s goals. By their nature, human beings are social animals, and this cannot be overlooked. Seemingly, inconsequential activities, such as mirroring body posture and sharing food and drink become very important to building rapport and trust.17

Trust: No Silver Bullet

As with any relationship between human beings, when a person chooses to trust, they are taking a risk. There may be times the other person lets you down or you let the other person down. War is not all unicorns and rainbows and has a way of bringing out both the best and worst in people. Even when a relationship weathers the storm of combat, the enemy still gets a vote. Trust is an important factor, but not the only important factor in COIN.

Counterinsurgents’ success is contingent upon their ability to employ all of the warfighting functions effectively and efficiently.18 Counterinsurgents must have the ability to gather intelligence of value and capitalize on it quickly. Additionally, for long-term success, the counterinsurgent must create a viable host-nation security force that will stay behind and provide a safe and secure environment. Without this force, the host-nation government will flounder, and ultimately, the counterinsurgents’ efforts will fail.

Additionally, insurgencies require an intricate web of critical factors, which the counterinsurgent can degrade or deny. These typically include one or more of the following: the ability to mobilize support, training, leadership, intelligence, inspiration, assistance, safe havens, financial resources, military support, and logistical support.19 The counterinsurgent should consider the application of a holistic operational design that employs all available joint, international, interagency, and multinational ways and means at disposal against the insurgent. Trust is critical, but no panacea.

Conclusion

In over a decade of continuous operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, American service members have fought a determined enemy while simultaneously earning the trust and confidence of partner militaries, police forces, and the people; the ones that will ultimately determine long-term success. Simply, if the decisive point of any military operations is where you start winning and the enemy starts losing, then earning and maintaining trust fits the definition of a decisive point in the context of the COIN fight.

Throughout history, when the weak face the strong in combat, the weak have often chosen insurgency as their way of war. As long as the U.S. enjoys the definitive overmatch it has today, future enemies will employ an asymmetric approach to counteract that advantage. These adversaries will not fight fair and likely employ AK-47s, IEDs, or cyber weapons vice multi-billion dollar tanks, fighters, or aircraft carriers. They will choose to fight in a manner where they stand some chance instead of facing America on its terms. As such, U.S. Soldiers must remain trained and ready to build trust on the battlefield of the future.

Notes

1 The names John Smith and Ahmad Khan were selected at random and do not represent any specific person living or dead.

2 FM 3-24, Counterinsurgency, 2006, 3-13, accessed 7 January 2014, http://www.fas.org/irp /doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf.

3 Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Operation Planning (2011): xxii, accessed 7 January 2014, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/dod_dictionary/data/d/10750.html.

4 Denise Rousseau, Sim Sitkin, Ronald Burt, and Coun Camerer, “Not So Different After All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust,” Academy of Management Review (1998), accessed 31 July 2013, http://portal.psychology.uoguelph.ca/faculty/gill/7140/WEEK_3_Jan.25/Rousseau,%20Sitkin,%20Burt,%20%26%20Camerer_AMR1998.pdf.

5 Aaron A. Bazin, “Winning Trust and Confidence: A Grounded Theory Model for the Use of Confidence-Building Measures in the Joint Operational Environment,” (diss., University of the Rockies, 2013), 85-101, accessed 7 January 2014, http://search.proquest.com/docview/1431981433?accountid=39364 or https://docs.google.com/file/d/0BxSlAno_dzmgWmtPLTFtZVAzT0U/edit#!

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid; Leonard Berkowitz and Anthony LePage, “Weapons as aggression-eliciting stimuli,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1967): accessed 7 January 2014, http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1967-16673-001.

13 Bazin, “Winning Trust and Confidence,” 87-101.

14 Ibid.

15 Beth Harry, “An Ethnographic Study of Cross-Cultural Communication With Puerto Rican-American Families in the Special Education System,” American Educational Research Journal, accessed 7 January 2014, http://aer.sagepub.com/content/29/3/471.short.

16 Bazin, “Winning Trust and Confidence,” 87-101.

17 Ibid.

18 U.S. Army, ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations (2012): 3-2, accessed 7 January 2014, http://armypubs.army.mil/doctrine/DR_pubs/dr_a/pdf/adrp3_0.pdf.

19 Daniel L. Byman, Peter Chalk, Bruce Hoffman, William Rosenau, and David Brannan, “Trends in Outside Support for Insurgent Movements,” RAND, accessed 7 January 2013 from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/congress/terrorism/.

LTC Aaron Bazin is a Functional Area 59 officer and currently works at Joint and Army Concepts Directorate at the Army Capabilities and Integration Center at Fort Eustis, Va. Previously, he served as U.S. Central Command as lead planner for the 2010 Iraq Transition Plan and other planning efforts. This work represents a synopsis of his research conducted for his doctorate in psychology. His operational deployments include Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Jordan.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print