Rally Point for Leaders: Building an Organization’s Mission Command Culture

by LTC Scott A. Shaw

Mission command — we all talk about it, and we all want to have it in our organizations. In his April 2012 white paper on mission command, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff GEN Martin Dempsey wrote: “Our need to pursue, instill, and foster mission command is critical to our future success in defending the nation in an increasingly complex and uncertain operating environment” where “smaller units enabled to conduct decentralized operations at the tactical level with operational/strategic implications will be the norm.”

GEN Raymond Odierno, Army Chief of Staff, has further stated “Done well, [mission command] empowers agile and adaptive leaders to successfully operate under conditions of uncertainty, exploit leading opportunities, and most importantly achieve unity of effort.”1 In the same speech, GEN Odierno stated that “Mission command is fundamental to ensuring that our Army stays ahead of and adapts to the rapidly changing environment we expect to face in the future.”

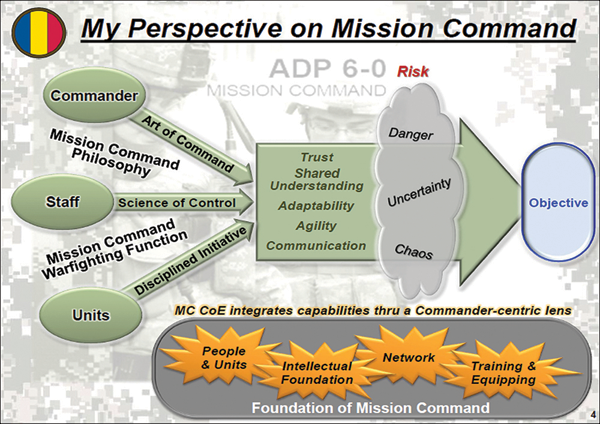

Finally, GEN Robert Cone, the commanding general of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, presented his perspective during the Association of the United States Army’s (AUSA’s)Mission Command Symposium on 20 June 2012 in Kansas City, Mo. (see Figure 1).

In order to get to the objective — and through the risks posed by the danger, uncertainty, and chaos produced by a complex operating environment — units must practice mission command in this age of tactical, operational, strategic, and fiscal uncertainty.

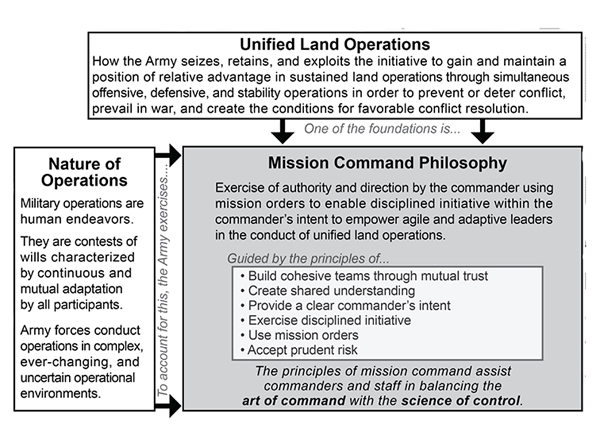

While the definition of mission command can be found in our doctrine, the question remains as to how to train mission command and further how to train mission command in the austere environment now facing the Army. This article will first briefly define mission command according to our Army doctrine and then prescribe a method that can be used to create a mission command culture using leader-prescribed readings within a unit, regardless of size. This article will point to an avenue for leaders to better themselves as individuals, but the primary focus is on building a unit plan — staff or troop unit — that can help a commander or staff leader train and educate subordinates. This unit plan must be focused on attaining the six principles of mission command:

- Build cohesive teams through mutual trust,

- Create shared understanding,

- Provide a clear commander’s intent,

- Exercise disciplined initiative,

- Use mission orders, and

- Accept prudent risk.2

In order to obtain a mission command culture inside of an organization, a commander or staff leader must create a cohesive organization based on shared understanding and mutual trust. The easiest, most cost effective manner to do this is through a directed reading program coupled with discussions led by the commander or staff leader to reinforce the readings. This kind of program creates a rally point for leaders within their organization.

Mission Command Defined

So what is mission command? Army Doctrinal Publication (ADP) 6-0, Mission Command, states that “Mission command is the exercise of authority and direction by the commander using mission orders to enable disciplined initiative within the commander’s intent to empower agile and adaptive leaders in the conduct of military operations.” A mission command philosophy is guided by the six principles that were listed above.

Pictorially, the relation from what the Army is tasked to conduct — unified land operations — to a mission command philosophy looks like Figure 2.

So that should clarify what it is, right? Maybe. Commanders can build cohesive teams quickly, but mutual trust and shared understanding is something that takes time. Further, discerning what prudent risk is at a leader’s level is very difficult. Prudent risk is “a deliberate exposure to potential injury or loss when the commander judges the outcome in terms of mission accomplishment as worth the cost.”3 That’s challenging for a company-level leader who’s never faced that sort of decision before. Those kinds of experiences cannot be taught in a classroom. They must be taught in a unit, and given our current fiscal state, they must be done for less than the cost of putting a Bradley on its side, followed by the subsequent recovery, and then a day or two in the field trains. But at least there’s an objective to drive toward. The objective is decentralized operations in a complex environment.

In order to achieve a mission command culture, a leader — any Army commander or staff leader — must pursue the six principles of mission command. A leader must build a cohesive organization through rigorous training that leads to mutual trust and shared understanding generated by a clear commander’s intent. An organization with those qualities will enable the commander to accept prudent risk because he or she knows that subordinate leaders will exercise disciplined initiative to accomplish the purpose of the operation outlined in the mission order.

When I was a platoon leader in Korea in 1997-1998, this was accomplished by going to the field and conducting gunnery, force-on-force training, and live fires on a quarterly basis evaluated by the appropriate level of trained evaluator. Staff sergeant master gunners evaluated every crew qualification, and the battalion commander with his staff evaluated each platoon. Hard training, coupled with the supervision and evaluation of commanders, is truly the best way to train an organization toward a mission command culture. While there are certainly units in our Army now that are still training at that level, there are also many units that are training at a lower readiness level due to the reduction in forces in Iraq and Afghanistan and the austere environment of which we are now part. The availability of training resources is surely not a guarantee of a mission command culture, but it may make things easier through repetition.

Whether a unit is training for a known deployment or not, a method is needed to foster a mission command culture. That method should be directed reading. Directed reading is relatively inexpensive in terms of training dollars and Soldiers’ lives and can provide the leader a classroom without casualties or loss of equipment. The only cost is time — the time to conduct the directed reading/discussion and the planning time associated with setting up a reading program. Unlike virtual or game-based training where the method is limited to the simulation’s abilities or participant throughput, directed reading allows for a large population of leaders to be educated simultaneously. Directed reading enables the leaders of a large organization to discuss a topic without significant training resource overhead.

Several commanders have used reading plans in the past with great success. COL Michael Kershaw regularly published a memo titled “From my Bookshelf” that he would pass out to officers inside and outside of the 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division. MG (then COL) H.R. McMaster published a reading list for the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment prior to their 2005 Iraq deployment that aimed to educate the leaders of the regiment on the complexity of the impending deployment. The efforts of both of these commanders produced leaders with a set of tools for a complex mission.

Each unit needs a different plan since each unit has a different state of readiness and a different timeline. Units are going to receive new leaders and lose others due to schooling or moves. A plan must be able to accommodate the arrival of new leaders as well as the exit of established leaders; it must also be flexible to change if given a new or amended mission.

Toward a Unit Reading Plan

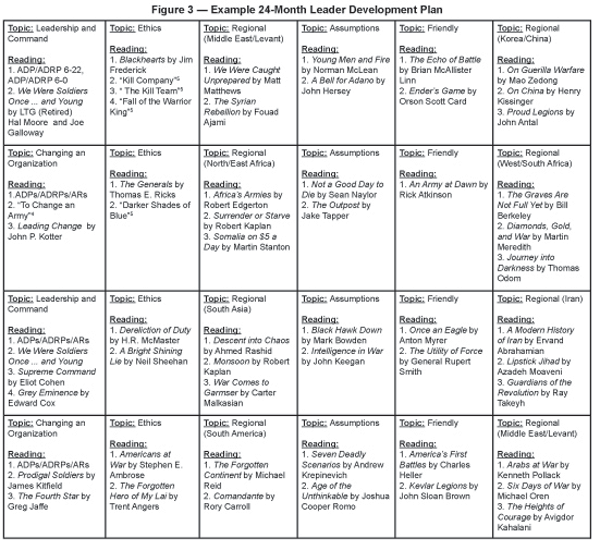

Figure 3 depicts an example of how leaders might array their leader development reading plan toward a mission command culture.

The unit or staff leader needs to assess his time available in the unit and plan his program accordingly. While some is better than none, a sequential program is much better than a “some” program because a sequential program equips a leader with an arsenal organized for battle. Most company and field grade leaders will be in a specific position for about a year with many rotating at the six-to-nine month mark. Centrally selected commanders at the battalion and brigade levels are largely locked in for 24 months. The chart, and this method, is organized to build a mission command culture by embodying the six characteristics presented previously. In order to accommodate the turnover in a unit, by the leader or the led, the program is broken into six-month cyclic segments. Most leaders will admit to learning through repetition or significant emotional event. This model provides for repetition so that the later possible significant emotional events are fewer and less intense. Most leaders are in position for 12 months and thus unable to do a third or fourth turn; however, a dedicated six- or 12-month period of leader development in many organizations will send better leaders to future units.

The cycle starts with what mission command is and what Army command policy is (and requirements derived from it), and then demonstrates methods by which leaders operate. It establishes a base, and then every six months it reinforces that base to accommodate new leaders or changes to policy. The cycle continues into month two with ethics in order to allow a commander or staff leader to lay out expectations for ethical behavior in the unit and the Army. Month three features a regional topic in order to give leaders familiarity with the global environment. Month four focuses on assumptions — right and wrong — made in combat or on the global scene that affect our tactical/operational/strategic situation in order to help leaders understand the pitfalls of making and then not re-visiting/re-validating their assumptions. Month five allows leaders to look at themselves — how the Army solves problems and what has been done incorrectly/correctly in the past that might positively impact future battles. Finally, month six takes a second look at our globe in another potential hot spot due to the amount of material required for a base of cultural awareness.

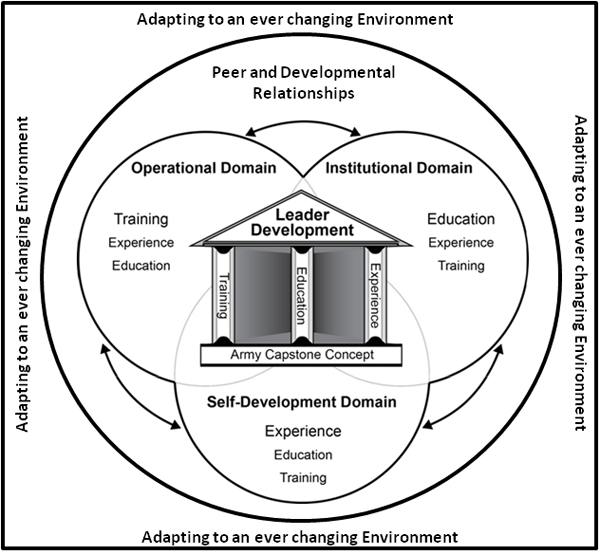

When determining how much training and education a leader needs in their unit, another question asked is “Why should I — a unit leader, commander, or staff leader — have to train this? Isn’t it covered at the basic and career courses?” It is, in fact, trained at all Army courses. Unfortunately, it is not trained with enough repetition to prepare for the complex environment in which Soldiers and leaders operate. After all, there are three domains of leader development — institutional, operational, and self-development that are used to educate leaders (see Figure 4).

It is the unit leader development programs that are lacking or have been pushed aside as our deployment-to-dwell cycles shortened over the past 12 years of war.

In order to become a more cohesive organization, the unit’s reading needs to be focused on that which enables commanders and leaders to rally around a discussion. Those discussions should be focused towards the following: leadership and command, ethics, planning, regional topics (with regard to both enemy forces and terrain), and the friendly situation.

Leadership and building a mission command culture are difficult, so they should be discussed first. In order to enable mutual trust, leaders must talk about ethics and the positive and negative ethical climates created by leaders of the past. It is those ethics that our leaders will take into the Baghdad streets and Korengal Valleys of the future.

Many of our recent tactical, operational, and strategic mistakes have resulted from invalid assumptions made or assumptions later revealed to be incorrect. It’s time to talk about faulty assumptions with leaders. The platoon leaders of today are the division, corps, or combatant command-level staff officers of 2025. They will plan our next conflict.

Commanders must talk to junior leaders about the regions of the world — not just Krasnovia and Atlantica, but North Korea and South Korea, and Iran and Qatar (along with the natural gas field that they share). It is time to discuss the reasons for conflict between the Tutsis and the Hutus and the importance of the Straits of Malacca.

Finally, commanders and their officers need to take a look at themselves. They need to learn about the Army’s culture and history and about why and how the organization functions as it does. The Army has a long history, and leaders of the present need to understand why leaders of the past chose the methods that were applied.

Leadership and Command

Leaders — both company and field grade — need more training and education on leadership and command to include:

- Army Regulation (AR) 600-20, Army Command Policy, and what actions it allows;

- What mission command is and is not in the organization;

- Changing organizations with a change model; and

- How to mentor junior officers and lead peers.

Leaders and commanders need to be guided through ADP 6-0 and Army Doctrinal Reference Publication (ADRP) 6-0 to ensure understanding of the true nature of mission command. Leaders and commanders need to be thoroughly instructed in ADP 6-22, Army Leadership, and ADRP 6-22 so there is more in-depth understanding of Army leadership. Company grade leaders need field grade leaders to talk to them about the Kotter and Starry models of change to help them better their organizations.4 To that end, leaders should read and discuss AR 600-20, ADP and ADRPs 6-0 and 6-22, as well as books on leaders in combat such as LTG (Retired) Hal Moore and Joseph Galloway’s We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, Supreme Command by Eliot Cohen, Grey Eminence by Edward Cox, Leading Change by John Kotter, Prodigal Soldiers by James Kitfield, and The Fourth Star by Greg Jaffe.

Ethics

Units perform in combat in the same manner that they are trained to perform in peace time. We stopped having “admin areas” in training situations because it created Soldiers that looked for “admin areas” in combat, resulting in shortcuts that cost them dearly. Leader development with regard to ethical conduct is no different. The leader that goes to combat with a misaligned ethical compass is the leader who will allow an atrocity to happen. This can further cause a native culture that views revenge as an acceptable cultural value to seek that revenge and spiral an already bad situation to horrible. Leaders must understand what is ethically acceptable and what is not. Case studies like those found our recent wars must be scrutinized to avoid those situations in the future. Books like Jim Frederick’s Blackhearts, Tom Ricks’ The Generals, Dereliction of Duty by MG H.R. McMaster, A Bright Shining Lie by Neil Sheehan, and The Forgotten Hero of My Lai by Trent Angers can all serve as case studies for commanders and staff leaders to discuss situations in a situational leadership laboratory. Further, articles like “The Fall of the Warrior King,” “Kill Company: Behind a War Crime in Iraq,” “The Kill Team: How U.S. Soldiers in Afghanistan Murdered Innocent Civilians,” and “Darker Shades of Blue: A Case Study of Failed Leadership” provide commanders and staff leaders additional material — and at a much cheaper cost than the books — to discuss with their officers in the pursuit of mutual trust and shared understanding about the conduct of the organization.5

Regional

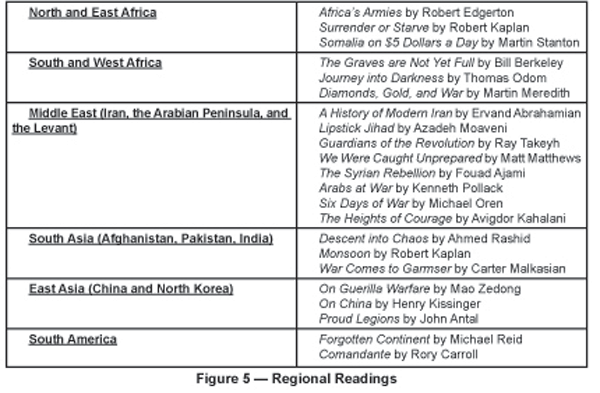

It has been proposed that we were unprepared for Iraq and Afghanistan because general purpose forces — brigade combat teams and those who support them — didn’t initially understand the culture of the locations into which we went. While both are very diverse — from Anbar to Diyala with Baghdad in the middle; from Nimroz to Kunar with Kabul in the middle — they can be broken down into pieces. If we are to stay relevant, we must be prepared to go anywhere in the world with some semblance of cultural awareness and quickly achieve functional cultural understanding. Our forces are already regionally aligned as our 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division is aligned to the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). We have learned that the cultural differences between the Sunni and Shia are vast; how much more so between South Africans and Ethopians or South Koreans and Indians? We will continue to engage in Africa, Europe, Asia (both Central and South), Australia, and South America — and while not a continent, of course the Middle East. In the commander’s period of instruction, he or she must give attention to regional education. Iran and Syria have special considerations different from those of the sub-Saharan region of “the continent.” The globe can easily be divided into several regions of study: 1. North and East Africa; 2. South and West Africa; 3. The Middle East with special emphasis on Iran, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Levant; 4. South Asia with emphasis on Pakistan and India; 5. East Asia with emphasis on China (including their relations with India, Afghanistan, and Nepal/Tibet) and North Korea; and 6. South America.

There are too many books to name on specific regions, but Figure 5 covers some I would start with.

Books lead to great discussions, but there are also many websites that can provide regional information on potential problem locations. Each combatant command provides reference material for hot spots in their areas of responsibility, but Foreign Policy magazine’s Failed States Index provides a concise look with further reference material links.6

Planning

Staffs and small unit leaders depend on assumptions and knowledge of procedures. A division-level assumption about the friendly, enemy, or the physical/human terrain turns into a company or platoon fact that might cost a Soldier his or her life. Our assumptions about enemies have led us to believe that the death or capture of individuals would surely crumble an organization, which later proved untrue. We make assumptions and then many times do not re-visit them to confirm that they are still valid or necessary. In order to better train our staff leaders and commanders about the danger of assumptions, leader professional development sessions could be built around the following books: Young Men and Fire by Norman McLean, A Bell for Adano by John Hersey, Not a Good Day to Die by Sean Naylor, The Outpost by Jake Tapper, Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden, Intelligence in War John Keegan, Seven Deadly Scenarios by Andrew Krepinevich, and Age of the Unthinkable by Joshua Cooper Romo. Each of these books demonstrates assumptions being made that were costly or could have been costly later and will help our future planners and commanders in the making and validating of their assumptions.

Friendly

Leaders often spend many hours dwelling on the aftermath of things gone wrong such as suicides, motorcycle accidents, attacks on combat outposts, or acts of indiscipline that lead to civilian casualties. Leaders spend a tremendous amount of time on the post-event period — the post-mortem — trying to figure out “why” something happened. Typically, this period results in many “a-ha!” moments — missed cues — in the connecting of the dots that led to the death of a Soldier, the loss of a base, or the deaths of civilians due to the acts of Soldiers. Many books describe events in which leaders missed cues that might have prevented the loss of life in Iraq and Afghanistan. These books could be read and then discussed over a month within the unit’s target audience. The target audience could then take that discussion back to their subordinate units and help junior leaders identify the dots that are out there to connect to make an operational picture, potentially giving an advantage or preventing further loss.

In order to attempt to gain the advantage in every situation, we must understand not only our potential adversaries and the terrain on which we may fight but also ourselves. Leaders must take a critical look at our Army in good and bad times. We need to read and discuss the battles that we have won and lost to see what factors, distant from the battlefield, caused victory or defeat. Books like The Echo of Battle by Brian McAllister Linn, An Army at Dawn by Rick Atkinson, Once an Eagle by Anton Myrer, The Utility of Force by General Rupert Smith, America’s First Battles by Charles Heller and William Stofft, Kevlar Legions by John Sloan Brown, and Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card provide hours of material that can be focused on a discussion of ourselves and our Army.

Training and education do not only have to deal with tactical, operational, or strategic issues; they need to be on garrison procedures as well. While not placed on the chart, any of the topics could be replaced or augmented by a month of discussion on garrison procedures. Junior officers often complain that they are micromanaged in garrison. We need to strive for a mission command culture in garrison, too, as it is where we will spend most of our time in the immediate future. While the Army Red Book describes many of the challenges leaders face, there are other training and educational opportunities for leaders.7 The recently published ADP 7-0 and ADRP 7-0, Training Units and Developing Leaders, as well as the Army Training Network (ATN) can help leaders better utilize the resources that they are charged with while still conducting terrific training. It is possible to conduct a quality live fire or situational training exercise within the allocation of ammunition, using land that is properly requested and used within the installation regulation, but it is only possible if commanders and staff leaders — company, battalion, and brigade — take the time to educate their subordinate leaders in a professional development session on training management. This session could be held once in the six-month cycle and cover the procedures for requesting land and ammunition, the specifics for the best use of ranges and training areas, and the conduct of a training meeting in your formation.

Conclusion

True, the program outlined above is a lot of reading in an already busy training or work schedule, but leaders must ask themselves and their subordinates, “Is the time that I am investing in our future leaders worth a Soldier’s life?” Of course the answer is “yes.” This education for our leaders must be planned with the same fervor as a platoon live fire or an upcoming rotation at a live or virtual combat training center. If planned with the same level of detail and protected like we protect morning PT or the rifle range, finding the time is easy. It was this kind of education — the directed study of terrain and culture by MG Fox Conner — that enabled General of the Army Dwight Eisenhower to plan the liberation of Europe from the Nazis.8 Directed reading and study, coupled with the training and education of our leaders in the institutional Army and their self-study, will create the warrior that is needed for the remainder of the 21st century and beyond. The reading and discussion plan laid out in these pages creates a rally point for leaders in preparation for fighting future wars in foreign lands against dedicated enemies.

Notes

1 Thomas Scott Gibson, “Army Leaders Discuss Mission Command, Army News Service, 19 June 2012, accessed 27 June 2013, http://www.army.mil/article/82091/Army_Leaders_Discuss_Mission_Command.

2 GEN Robert Cone, “Mission Command in the Army of 2020,” AUSA Institute of Land Warfare Mission Command Symposium, 20 June 2012, accessed 27 June 2013, http://www.ausa.org/meetings/2012.

3 ADP 6-0, Mission Command, iv.

4 John P. Kotter, Leading Change (Boston: Harvard Business Review, 2012); GEN Donn A. Starry, “To Change an Army,” Military Review, LXIII, March No. 3 (1983): 20-27.

5 Articles referenced:

Dexter Filkins, “The Fall of the King,” The New York Times Magazine, 23 October 2005, accessed 28 June 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/23/magazine/23sassaman.html.

Raffi Khatchadourian, “The Kill Company,” The New Yorker, 6 July 2009, accessed 28 June 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/07/06/090706fa_fact_khatchadourian.

Mark Boal, “The Kill Team: How U.S. Soldiers in Afghanistan Murdered Innocent Civilians,” Rolling Stone Magazine, 27 March 2011, accessed 28 June 2013, http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-kill-team-20110327#ixzz2W2QLyZHo.

MAJ Anthony T. Kern, “Darker Shades of Blue: A Case Study of Failed Leadership,” Industry CRM Developers, accessed 28 June 2013, http://www.crm-devel.org/resources/paper/darkblue/darkblue.htm.

6 The Failed State Index for 2012 can be found at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/failedstates2012.

7 Army Health Promotion Risk Reduction Suicide Prevention Report 2010, accessed 28 June 2013, http://csf2.army.mil/downloads/HP-RR-SPReport2010.pdf.

8 Mark Perry, Partners in Command: George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower in War and Peace (NY: Penguin, 2007), 44-46.

LTC Scott A. Shaw is the deputy chief of operations, III (U.S.) Armored Corps, Fort Hood, Texas. He previously served as the S3 for the 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Hood; Contingency Operating Site Kalsu, Iraq (Operation New Dawn); and Camp Buerhing, Kuwait (Operation Spartan Shield). His other previous assignments include serving as chief of Military Transition Team 235, Diyala, Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom); commander, A Company, 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, Fort Drum, N.Y., and Baghdad, Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom); commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division, Fort Drum and Kabul, Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). LTC Shaw has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Arkansas and master’s degrees from Norwich University and the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print