Communicating at Home: The Relevancy of Inform and Influence Activities in the Garrison Operational Environment

by MAJ James Pradke

Army doctrine, specifically Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 6-22, Army Leadership, posits, “The Army profession is a calling for the professional American Soldier from which leaders inspire and influence others.” There exists a misperception in the garrison operational environment, however, that inspiration and influence responsibilities pertain only in deployed operational environments. This does not imply that inspirational leaders in garrison are not existent but that there exists, in contrast, little effort to understand and utilize legitimate influence activities to provide purpose, direction, and motivation to the garrison formation.

From training to discipline, the art of inspiration and ability to influence play an integral role in the daily activities of all military leaders. “Leadership is the process of influencing people...”1 The art of influence lies congruent with provisional responsibilities of purpose, direction, and motivation demanded of leaders to accomplish any given mission at any time.2 Considering influence as the ability to motivate and inspire, information delivered via expressed words and actions, demonstrating purpose and direction, forms the foundation upon which influence activities in a garrison environment gain effect.

The purpose of this article is to first define garrison inform and influence activities and thus create awareness for military professionals. Second, this article encourages leaders to hold information operations (IO) professionals accountable for the development of initiatives in support of leadership, embracing inform and influence activities as a means to inspire. Third, this article inspires IO professionals to consider the utilization of creative garrison inform and influence activities to positively influence Soldier actions otherwise contrary to the policies and decisions of brigade leadership.

Defining Garrison Inform and Influence Activities

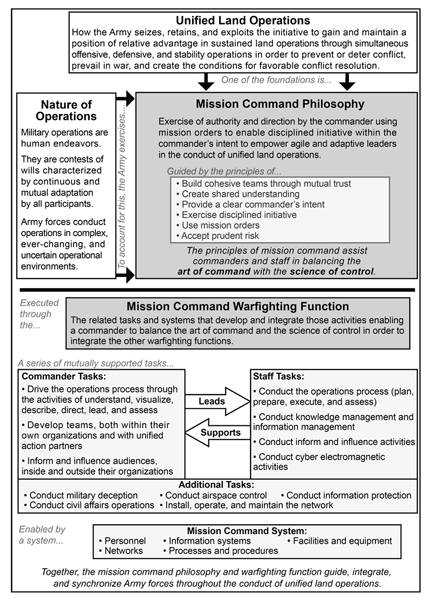

Disappointingly, IO professionals throughout the garrison operational environment are misunderstood and underutilized. One challenge facing the IO community stems from within. By far, the IO professional’s misinterpretation of responsibilities within a garrison operational environment is the greatest detriment to success. The misinterpretation and lack of ability to communicate the IO professional’s contributions to a garrison staff, regardless of echelon, breeds confusion amongst leaders and results in a misappropriation of a key enabler. Skeptics within the IO force continue to question their existence as a critical component in the mission command warfighting function. There are those within the community who feel strongly that garrison IO professionals should perform additional staff responsibilities within the operations or fires staff function. There is a reason inform and influence activities serve a key role in mission command as a warfighting function. Within the organization, “inform and influence activities are the integration of designated information-related capabilities to synchronize themes, messages, and actions” with intent to inform and influence.3 This definition justifies garrison inform and influence activities as a mission-essential synchronized function.

The garrison operational environment is unfamiliar to those leaders who have found themselves in continuous rotations to deployed operational environments. Immediately upon return from deployment, many Soldiers found themselves being recycled in preparation for another rotation. According to a USA Today article on repeated troop deployment, 47 percent of the active duty deployed force experienced multiple deployments as of 2010.4 Understanding the garrison operational environment may prove challenging for a force transitioning from a rigorous deployment cycle to a more regular training and maintenance cycle. That said, today’s garrison operational environment consists of a constrained force of Soldiers and leaders struggling to adjust from high operational tempos with forgiving standards to regimented schedules with stricter policies of adherence.

The Garrison Operational Environment

Operational environments influence employment capabilities and bear on the decisions of the commander.5 Commonalities between a garrison operational environment and a deployed operational environment are the information environment (including cyberspace), physical areas, and relevant information systems. The nature and interaction of systems paired with an understanding and visualization of the environment will affect how the commander plans, organizes for, and conducts garrison operations.6

Not to be confused with the physical environment, the information environment consists of information and cognitive dimensions as well as varied locations and systems by which Soldiers within the organization receive and process information. The information environment may include dissemination of information via leadership throughout the formation, display boards, family readiness groups, social media, garrison and local cable television stations, post and local newspapers, and organizational activities, to name a few. The garrison information environment includes any facet of information dissemination that a commander may use to inform the organization.

Physical areas are those where Soldiers reside, train, operate, and socialize. These may include the favorite local hang out or bar, housing units, the Post Exchange, gyms, outdoor recreation facilities, the chapel, local shopping malls, motor pools, ranges, training areas, conference rooms, and more. Defined, the garrison physical area includes physical locations where leaders engage Soldiers with intent to inform, inspire, and influence.

Garrison operational environment systems consist of ways of delivery (ends = ways + means) regardless of desired end state. These are the systems leaders rely upon to inform, inspire, and influence. From unit Facebook pages to standard policy memorandums, from battalion commanders to squad leaders, the more efficient leaders are in using creative ways of information dissemination, the more effective they are in building initiatives which have impact and long-standing results. Commanders understand, visualize, describe, and direct in the garrison operational environment as they would in a deployed operational environment. Using the information environment, physical environment, and relevant information systems, commanders build initiatives to achieve outcomes (see Figure 1).

Doctrine

Contrary to what some in the IO professional community believe, current doctrine provides ample definition supporting garrison responsibilities of information operations to the lowest level. These responsibilities are not defined in FM 3-13, Inform and Influence Activities. FM 3-13 merely prescribes the function, tasks, and conduct of inform and influence activities within a given environment. Garrison inform and influence responsibilities are discussed in ADRP 6-22; ADRP 6-0, Mission Command; arguably in ADRP 3-0; and inherently lie within any doctrine discussing leadership.

Inform and influence activities support a leader’s responsibility to influence and motivate people to “pursue actions, focus thinking, and shape decisions.”7 It is important to note these responsibilities are relevant to the organization. Whether deployed or in garrison is inconsequential. The military professional who understands that inform and influence activities are a function of command support adopts the responsibilities of the commander as his own. Simply, the IO professional, regardless of environment, supports the commander’s initiative to “influence and motivate the formation to achieve goals, pursue actions, focus thinking, and shape decisions for the greater good of the organization.”8

ADRP 6-0 fails, somewhat, in defining the broader scope of responsibilities of an IO professional. ADRP 6-0 limits inform and influence activities to three primary functions: public affairs, military information support operations (MISO), and Soldier and leader engagement respectively. The challenge with this is the military community tends to embrace these three capabilities, along with FM 3-13, as the complete scope and function of the information operations professional. Leaders, in addition to those just mentioned, question the relevancy of inform and influence activities in a garrison environment arguing that functions performed by the S7/G7 in garrison are redundant to those already performed. The information operations professional is neither a public affairs officer nor do they conduct MISO. Deployed and in garrison, IO, public affairs, and MISO professionals provide partnered capabilities which nest within the overall initiatives of the commander. In garrison, the IO professional designs and coordinates large scale information initiatives utilizing multiple enablers to support a leader’s requirement to provide purpose, direction, and motivation. When in the absence of guidance, the IO professional is responsible to the commander and the initiatives inherent within the command.

IO professionals grow frustrated when efforts to establish garrison inform and influence activities are thwarted by those ignorant to the relevancy toward achieving leadership outcomes (healthy climates, fit units, engaged Soldiers and civilians, stronger families, sound decisions, expertly led organizations, and mission success). To achieve these outcomes, IO professionals must be persistent in defining the demographic of the organization, establishing the garrison inform and influence activities working group (G-IIAWG), and developing initiatives which support leadership efforts to achieve outcomes previously mentioned.

Overcoming Varied Demographics and Culture of the Unit

The understanding of organizational composition or demographics provides information necessary for shaping themes, messages, and talking points that adequately address command information initiatives. Brigade, division, and corps level organizations consist of varied sub-audiences throughout. Thus, messages and talking points delivered via a single system may be better disseminated through multiple delivery systems each of which is designed to inform a specific audience. Consider the 2011 campaign, “The Army Profession.” A new private first class in the Army may define professionalism in a completely different manner than a veteran sergeant first class. Additionally, the manner in which they understand the Army’s definition of professionalism also differs. Drilling down even further, a married private first class may receive and define professionalism on a different level than a unmarried private first class. This isn’t to say one is more educated than the other. Simply stated, different demographic groups throughout organizations receive and understand information differently based on culture, upbringing, status, and experience. While there exist exceptions to the rule, messages designed for a specific demographic are better received than those delivered to broad audiences.

The Garrison IIAWG

The G-IIAWG is responsible for supporting a leader’s information end state by providing enabling capabilities which diversify ways of delivery through the use of varying agency means. The G-IIAWG embraces support agencies in garrison as partners whose interests align with leadership outcomes sought by commanders. For example, a Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT) commander whose interest lies in improving the fitness and wellness of his unit may expect to see a working group with enablers and partners from the military family life consultants, the garrison wellness center, family advocacy, the unit surgeon, suicide prevention, the master fitness trainer, substance abuse prevention, county and state police, provost marshal, judge advocate general, public affairs, S3, chaplaincy, social services, and others. The coordination and integration of all activities related to unit fitness thus becomes the responsibility of the IO officer while execution of those activities remains the responsibility of those agencies. The working group meets regularly to measure the effectiveness of its performance on specific information initiatives. The commander relies on the working group, consisting of garrison and off-post agency experts, to provide ways and means to inspire and influence Soldiers to achieve improved individual and organizational levels of fitness.

Conclusion

To develop garrison initiatives aimed at organizational goals, IO professionals must take the time to understand leadership aims and objectives. The IO officer (along with the G-IIAWG) is capable of defining measures of performance and measures of effectiveness which demonstrate progress and clarify needs for adjustment. Quantifiable measures demonstrate overall initiative effectiveness, define whether or not the operational information environment is changing, and aid leaders in decision-making responsibilities. To understand command objectives, the garrison operational environment, and how to shape future initiatives, the relationship between the IO officer and the leader requires open communication and information exchange. The stronger this relationship, the more effective the overall thematic design.

In summation, garrison inform and influence activities are no less relevant than those while deployed. While the operational environment is clearly different, the understanding, visualization, and description of the information and physical environments paired with the use of varied systems remain inherently the same. As in a deployed environment, the G-IIAWG consists of civilian agencies whose interests and means support the commander’s desired end state. The working group meets regularly to assess progress and measure the effectiveness of its performance. As leaders apply garrison inform and influence activities to achieve outcomes defined in ADP 6-22, they should understand the relevancy of their information operations officer and hold IO professionals accountable for the development of initiatives focused on garrison leadership outcomes. This is best achieved through open communication and mutual understanding. According to ADP 6-22, leaders inspire and influence people to accomplish goals. Army leaders motivate people to pursue actions, focus thinking and shape decisions. These result in the betterment of the organization and encourage growth which ultimately leads to mission success — the goal of every leader.

Notes

1 ADRP 6-22, Army Leadership.

2 Ibid.

3 ADRP 6-0, Mission Command.

4 Gregg Zoroya, “Repeated deployments weigh heavily on U.S. troops,” USA Today, 13 January 2010, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/military/2010-01-12-four-army-war-tours_N.htm

5 JP 3-0, Joint Operations.

6 Ibid.

7 ADP 6-22.

8 Ibid.

MAJ James Pradke is currently a training developer with the U.S. Army Information Proponent Office at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. His previous assignments include serving as the brigade S7, 4th Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT), 2nd Infantry Division, Fort Lewis, Wash.; military advisor with a military transition team, 3rd SBCT, 2nd Infantry Division, Baqouba, Iraq. He is a graduate of the Command and General Staff Officer College, Fort Leavenworth; Functional Area 30 Qualification Course, Fort Leavenworth; Combined Logistics Captains Career Course, Fort Lee, Va.; Transportation Officer Basic Course, Fort Eustis, Va.; and Officer Candidate School, Fort Benning, Ga. MAJ Pradke has a master’s degree in international relations and conflict resolution from American Military University and a bachelor’s degree in music from DePauw University. He is a doctoral student at the University of Kansas.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print