America’s First Company Commanders

by LtCol (Retired) Patrick H. Hannum, USMC

George Washington takes command of the American Army at Cambridge in 1775. (Engraving by C. Rogers from painting by M.A. Wageman.) (U.S. Archives)

Most Soldiers know the birthday of the U.S. Army is observed on 14 June each year, but few can explain what happened on that day in 1775. This is a story that every Soldier needs to know. What occurred that day was a very modest beginning of a national army — the Continental Army. The Continental Congress authorized three different colonies to recruit 10 companies of Infantry, not just Infantry companies but rifle companies. These 10 companies needed Soldiers and leaders resulting in the selection of 10 (and later 13) men to command the newly authorized companies — the first company commanders in the national army.

The American Colonies went to war against the British Army on 19 April 1775 at Lexington Green with a force of volunteer colonial-controlled militia. Since there was no nation and no national army, the colonies only coordinated their independent activities through the Continental Congress. As the military situation unfolded in the spring of 1775 and as a collection of militia from several colonies converged around Boston, it became evident a national army with formal leadership accountable to the Continental Congress was an absolute necessity to execute coordinated military efforts of the United Colonies.

The army that laid siege to the British Army at Boston in the spring of 1775 was a regional rather than a national army. This New England regional army, called the “Army of Observation,” initiated the siege of Boston and fought the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775. This Army of Observation, reinforced by units from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia in August 1775, formed America’s first truly national army.1 The New England militia armed itself with many different types of weapons, primarily smoothbore weapons or muskets because the settled farming areas of New England lacked a hunting tradition requiring rifled weapons. Rifled weapons, first introduced to North America by the Swiss immigrants and perfected by American gun makers, were found primarily in the western portions of the middle and southern colonies. Congress clearly understood the differences between muskets and rifles when they made the decision to form the first units of the national army.2

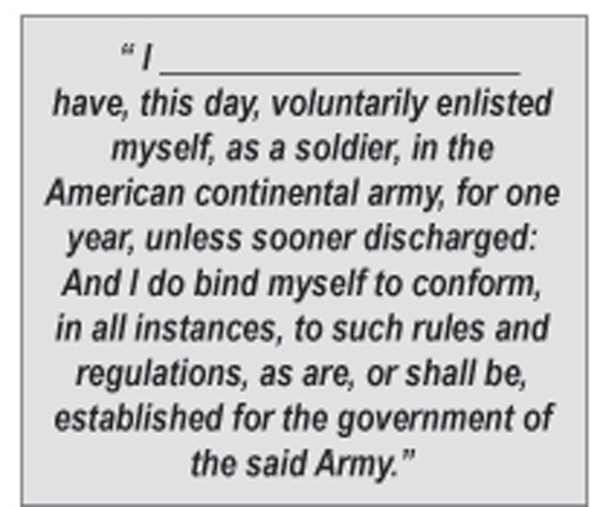

The day prior to George Washington’s appointment as the commander in chief of the Continental Army, Congress began the process of building a national army. The core of the national army began to form on 14 June 1775 when the Continental Congress authorized the formation of 10 rifle companies — six from Pennsylvania and two each from Maryland and Virginia.3 Congress specified the term of enlistment for the riflemen as one year and set the strength of the companies at one captain, three lieutenants, four sergeants, four corporals, a drummer or trumpeter, and 68 privates, for a total of 81 men.4 The simple wording of the enlistment contracts of the riflemen is outlined in . Congress specifically authorized rifle companies. Rifles were standard weapons on the colonial frontier or backcountry. Frontier riflemen were excellent marksmen; Congress appropriately recognized the military value of soldiers who could kill the enemy at over 200 yards. The men in the first rifle companies provided their own clothing and rifles, facilitating the rapid recruitment, organization, and deployment of these initial units.5

When the Continental Congress took action to form the Continental Army on 14 June 1775, they envisioned recruiting these 10 companies of riflemen for service as a light infantry force reporting immediately to George Washington for operations around Boston. The resounding response by the various county committees in Pennsylvania, specifically in the western and northern counties, prompted Congress on 22 June to authorize eight Pennsylvania companies that would form a battalion.7 On 11 July, Congress added a ninth Pennsylvania company.8 General Washington’s first national army consisted of these 13 rifle companies, with the nine Pennsylvania companies formed into a battalion. When Congress approved the rifle companies, they authorized the respective colonies to identify the officers Congress appointed to command. This initiated the practice that continues to this day by which Congress appoints all commissioned officers in the U.S. military.9

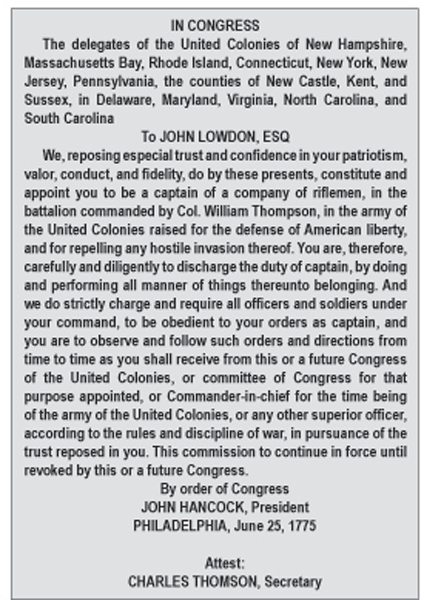

Figure 2 contains a copy of one of the surviving commissioning appointment letters offered to the rifle company commanders. This document was issued to John Lowden from Northumberland County, Pa., and signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. The appointment letters to the first company commanders in our first national army read strikingly similar to those issued by the U.S. Congress to commissioned officers serving in the armed forces today.

Because the colonies and counties nominated the officers to receive Congressional commissions, local politics played a major role in determining who would command the initial companies formed from their respective colonies. The empowerment of local revolutionaries who collaborated through local Committees of Safety and Correspondence came to dominate the political process. Nowhere was the transition from conservative loyal colonial governments to those favoring separation from Britain more evident than in Pennsylvania where the radicals gained control of the government and revised the state constitution.11 This transition from a loyal conservative government to one dominated by revolutionaries or patriots resulted in the appointment of men committed to the revolutionary cause to command the first 13 companies to make up the new American Army.

Unlike today’s system of identifying companies by a letter of the alphabet, revolutionary era units were named for their company commander, even after that individual departed from the parent regiment or battalion. This practice combined with non-standard record keeping and the loss of many personnel records early in the revolution complicates tracking units to the company level.12 This practice also links the names of the first 13 company commanders directly to the companies they recruited for their first year of existence. Despite the difficulties associated with linking history and lineage of colonial and revolutionary era military units, one unit in today’s U.S. Army that draws its lineage from the original rifle companies is the 201st Field Artillery Regiment, West Virginia National Guard. This unit traces its history to the Captain Hugh Stephenson Company drawn from members of the Berkley County (Va.) militia. The Berkley County militia traces its roots to 1735.13 Many units in today’s U.S. Army have a very complex lineage. This complex lineage is perhaps one reason the Army has failed to embrace the simple facts associated with these 13 rifle companies. They were the first units in the national army. That army grew and changed many times between 1775 and 1783 when it was disbanded. But the simple fact remains; it was the formal element of military power that helped create the United States of America. Without this Army that began with 13 rifle companies, America in its current form would not exist today.14

The men selected to command the rifle companies were also responsible for recruiting the enlisted men to serve in the ranks. These leaders all came from the frontier or backcountry of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia where a strong patriot sentiment existed. The first 13 captains appointed to serve as rifle company commanders were from Maryland (Michael Cresap and Thomas Price), Pennsylvania (James Chambers, Robert Clulage, Michael Doudel, William Hendricks, John Lowdon, Abraham Miller, George Nagel, James Ross, and Matthew Smith), and Virginia (Daniel Morgan and Hugh Stephenson). The nine Pennsylvania companies were organized into the Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion, which holds the distinction of being the first battalion in the national army and was initially commanded by Colonel William Thompson.

Soldiering is always a demanding business; the conditions during the American Revolution proved challenging for the new company commanders. Three of these men died during their first few months of service (one in combat) and one was captured by the British. As the war progressed, six moved on to receive promotions to the field grade rank; five achieved the rank of colonel and went on to command regiments; one became a general officer; and two went on to have political careers. More importantly, these men responded quickly to the call to form companies, led their fellow citizens, and moved to Boston in defense of American ideals and liberty. These ideals were not yet national concepts; the formation of a national army helped to spread these concepts originally formed through congressional association and Committees of Safety and Correspondence, concepts accepted today by most Americans as unalienable rights. Concepts of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness addressed in the Declaration of Independence were possible intangible motivators, but the publication of the Declaration of Independence was a year in the future when these men accepted the first commissions offered by the Continental Congress to lead companies in opposition to British rule. These men were appointed to serve by the United Colonies, not the United States.15 These men were on the leading edge of a new concept of government, one that recognized individual freedoms. Americans were in the process of creating a nation without an existing nation state.16 These men recruited, organized, and began moving their companies toward Boston within four weeks of Congressional authorization. They were dedicated men, energized by concepts that not only led to America’s independence but were later enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Seven of the Pennsylvania rifle companies, combined to form Thompson’s Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion, quickly moved to Boston.17 The Pennsylvania rifle companies did not initially move as a battalion but tended to link-up and follow the same basic route of march. The two Virginia companies made it a competition to reach Boston first. The units marched 23 to 30 miles per day, making the trip to Boston in three weeks. The companies tended to follow similar routes converging as they passed near New York City. Chambers’ and Hendricks’ companies started together in Carlisle on 13 July, and Miller’s company joined them at Easton on 24 July. Morgan’s company of Virginia riflemen departed Winchester on 14 July and joined the growing body on 27 July at the Sussex County Court House (today Millstone) in New Jersey. Smith’s company may have been a few days ahead of the other Pennsylvania companies. A letter from Hartford, Conn., dated late July 1775 reported about 200 “Paxtang Boys” — dressed and painted in Indian style — passed through on their way to Cambridge. These men reinforced the Army of Observation and helped form the nucleus of the new Continental Army. Movement to Boston was not without its interesting moments.18

The men departed their homes during mid-July and arrived in Boston by early August. Independent and fiercely loyal to the revolutionary cause, these riflemen caught the attention of the citizens they encountered along their route of march. Private George Morison of Hendricks’ company left the liveliest account of the Pennsylvania riflemen’s journey to Boston in his journal entries from 13 July to 9 August 1775. After stopping in Reading for clothing and supplies, Hendricks’ company proceeded to Bethlehem where they were impressed by the beauty of young nuns from the local convent. After crossing into New Jersey on 26 July, Hendricks’ company took a break from marching and entertained themselves by tarring and feathering a loyalist. Several days later, on 3 August, in Litchfield, Conn., the Pennsylvania troops again tarred and feathered a loyalist brought in by a Maryland company, one of the two Maryland rifle companies also in route to Boston. They added additional insult by making the man “…drink to the health of Congress…” before being drummed out of town. Hendricks’ company arrived at Cambridge on 9 August.19 Morgan’s company arrived on 6 August, Stephenson’s on 11 August, and Cresap’s and Price’s on 9 August.20 All nine companies of Thompson’s Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion arrived in Cambridge by 18 August, providing George Washington with 13 companies of skilled marksmen and additional discipline problems to compound those experienced with the thousands of New England militia already present around Boston.21

Upon arrival at Cambridge, the rifle companies gained the attention of the British Army, the New England men serving there, and the American commander (Washington). Caleb Haskell of Newburyport, Mass., noted the arrival of three companies of riflemen on 8 August 1775. The riflemen announced their arrival to the British the same day by killing a British sentry. In a letter dated 13 August 1775, Captain Chambers reported action against the enemy, resulting in “forty-two killed and thirty-eight prisoners taken,” including four captains. Captain Chambers also indicated, “The riflemen go where they please…” The riflemen combined their marksmanship skills and independent and aggressive behavior to harass the enemy.22 Riflemen also impressed the New England troops with their marksmanship skills when not on duty by shooting at targets.

In an August 1775 diary entry, Dr. James Thacher noted:

“Several companies of riflemen, amounting, it is said, to more than fourteen hundred men, have arrived here from Pennsylvania and Maryland; a distance of from five hundred to seven hundred miles. They are remarkably stout and hardy men; many of them exceeding six feet in height. They are dressed in white frocks, or rifle-shirts, and round hats. These men are remarkable for the accuracy of their aim; striking a mark with great certainty at two hundred yards distance. At a review, a company of them, while on a quick advance, fired their balls into objects of seven inches diameter, at the distance of two hundred and fifty yards. They are now stationed on our lines, and their shot have frequently proved fatal to British officers and soldiers who expose themselves to view, even at more than double the distance of common musket-shot.”23

The riflemen of the American Army had arrived.

George Washington faced many issues when he arrived at Cambridge to organize and lead the Continental Army. One of his main challenges was establishing good order and discipline. The riflemen’s independent behavior, part of their culture in the “backcountry,” added to Washington’s problems in establishing firm and standard discipline in the new national army. Washington required the independent-minded riflemen to perform guard and entrenching duties along with New England units. The riflemen detested these assignments. The riflemen in Captain Ross’s company broke open the local guard house and removed one of the sergeants “confined there for neglect of duty and murmuring.” Several senior officers seized the sergeant and ordered him confined in the guard house in Cambridge. Thirty-two members of Ross’ company returned about 20 minutes later and headed to Cambridge to release the sergeant. Washington, notified of the events, arrived on the scene with Generals Lee and Greene. About 500 New England troops, billeted near the riflemen, responded and ended the incident by surrounding Ross’s men with fixed bayonets one-half mile away on a small hill. This incident ended the immediate threat of mutiny by the riflemen, but Washington’s attempts to instill military discipline in these independent-minded men continued.24

Duty in the lines around Boston proved dangerous. On 27 August, 50 Pennsylvania riflemen engaged in covering party duties supporting the construction of an artillery battery position on Ploughed Hill when Mr. Simpson, a volunteer in Smith’s company, had his foot ripped from his body by an enemy cannon ball. Washington visited the wounded soldier shortly after the incident. The wound necessitated amputation of Simpson’s leg and he died the next day. Simpson’s death rarely receives any notice. However, his death likely marks the first combat casualty in the national army.25

About the time the riflemen arrived at Boston, Washington had a meeting with a bold and aggressive warfighter, Colonel Benedict Arnold. During their meeting, Arnold proposed an attack into Canada to seize Quebec City by advancing through the Maine wilderness, supported by an attack up the Hudson River Valley to seize Montreal. Washington liked the double envelopment concept, accepted a plan prepared by Arnold, and ordered the expedition. With fall quickly approaching, speed in execution was essential if Arnold’s force had any chance of arriving at Quebec before winter set in.26

Arnold’s expedition to Quebec offered Washington an opportunity to send elements of the new national army with the New England troops, making this the first offensive action involving forces representing the United Colonies, an important political statement. Washington approved detaching three of the 13 rifle companies to accompany Arnold. The company commanders of the rifle companies cast lots to determine which units would join Arnold’s expeditionary army. Captain Morgan of Virginia and Captains Hendricks and Smith of Pennsylvania provided the riflemen to supplement the bulk of the force (10 companies of musket men from the New England states).27

In attempting to task organize his army for the movement to Quebec, Arnold experienced resistance from the three rifle company commanders. They insisted their chain of command ran through their chosen leader, Captain Morgan, to Colonel Arnold, and no other man would command them. This was a simple manifestation of their independent frontier culture. Morgan, Hendricks, and Smith also explained they held commissions from the Continental Congress and refused to subject themselves to command by New England militia officers.28 Arnold conceded the point and placed Morgan in overall command of the three rifle companies, forming the army’s first division. With the issue of command settled, Arnold’s force departed Fort Western on the Kennebec River on 25 September, commencing an epic struggle against the wilderness.29

Arnold’s force, including the rifle companies, began the expedition from Cambridge on 11 September 1775, and after extreme hardship, 10 of the original 13 companies assigned arrived on the north side of the Saint Lawrence River at the gates of Quebec on 14 November. Included in these 10 companies were the three rifle companies. The slow movement, loss of physical stamina, and lost and damaged weapons and equipment due to the unforgiving Maine wilderness closed the window of opportunity for an immediate attack into Quebec City. Arnold had to wait for the American forces advancing up the Hudson River Valley to link up with his force that survived the trek through the Maine wilderness, which numbered less than 600 effectives.

When this link-up occurred in early December, Brigadier General Montgomery and Colonel Arnold immediately made plans for an attack of the fortress of Quebec. In the assault on 31 December 1775, the Americans were repulsed with heavy loss. Montgomery, the overall commander, was killed (the first general officer killed during the revolution), and Arnold was wounded; the three rifle companies suffered heavily in killed, wounded, and captured. Hendricks was killed, Morgan was captured, and Smith was absent, likely because he was ill. Lieutenant Steele led Smith’s company and was captured after being wounded in the hand, losing three fingers. Three of the 13 rifle companies making up the new national army ceased to exist after the attempt on Quebec. Morgan’s and Smith’s careers in the Continental Army were not over, however. Morgan was eventually paroled. Smith continued to serve during the winter near Quebec and during the spring-summer retrograde from Canada down the Hudson River Valley.30

Morgan’s subsequent military service is iconic. His service to the nation and the Continental Army resulted in his identification as the “Revolutionary Rifleman.” Morgan is best known for his victory over Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens, S.C., in January 1781.31 Morgan remained a controversial figure even in death. In 1951, a group of preservationists from South Carolina showed up at Morgan’s grave in Winchester, Va., determined to move his remains to the Cowpens Battlefield in South Carolina, where Morgan would be properly enshrined. Morgan remained in Winchester, and the descendants of his original rifle company helped dedicate a more appropriate granite monument.32 Smith’s subsequent military service as a major and lieutenant colonel in the 9th Pennsylvania has recently come to light and is awaiting further documentation. Smith is interred in Warrior Run Cemetery near Milton, Pa.; local militia accompanied his body to the cemetery, rendering a 21-gun salute. Plaques provided by the Masonic order and a Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Roadside Marker commemorate his service to the nation. Both Morgan and Smith went on to have political careers prior to their deaths in 1802 and 1794, respectively.

The 10 remaining rifle companies participated in siege activities near Boston during the winter of 1775-76 while the surviving members of the three rifle companies in Quebec either suffered in prison cells or continued the siege outside the walled city of Quebec. On 9 November 1775, the riflemen responded to the British raid at Lechmere’s Point in Cambridge where a number of riflemen received wounds, but none were killed.33 After the evacuation of Boston by the British, Washington began repositioning his forces south to defend New York City and the surrounding area. The rifle companies began moving to New York during mid-March 1776.34 Stephenson’s Virginia company and the two Maryland companies (Cresep’s — now commanded by Moses Rawlings — and Price’s — commanded by Lieutenant Otho Holland Williams) operated from Manhattan and Staten Islands. Thompson’s remaining seven companies, later designated the 1st Continental Regiment on 2 January 1776 (after 7 March 1776 was under the command of Colonel Edward Hand) operated on Long Island patrolling the southwest beaches for signs of British amphibious operations.35

Because the original rifle companies enlisted for only one year, their enlistments expired on 30 June 1776. Many of the original soldiers reenlisted and served in the new or reorganized units created from these original 10 surviving companies. The men from the three companies captured at Quebec and fortunate enough to survive their imprisonment, returned on parole to New York in September 1776. Much changed during the first year of war for these original rifle companies. Of the original 13 companies, three were essentially destroyed at Quebec although Smith’s company (with Smith still in command) may have retained some unit cohesion at Quebec and mustered the remaining riflemen, some whom were sick and did not participate in the attack on 31 December 1775. Hendricks’ and Morgan’s companies, with Hendricks dead and Morgan captured, suffered such high casualties the units essentially ceased to exist as companies.36

Both Maryland companies had new commanders. The remaining Virginia company continued under the command of Captain Stephenson until his promotion to colonel to command the new regiment that included the Maryland and Virginia companies.37 This regiment, formed 1 July 1776 as an extra Continental Regiment (the Maryland Virginia Rifle Regiment), contained four Maryland and four Virginia companies. As the one-year enlistments of men initially members of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion (later designated as the 1st Continental Regiment) expired, at least 240 enlisted men reenlisted into the new 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, including some of Hendricks’ and Smith’s men paroled at Quebec. Of the original nine company commanders, only Clulage and Ross remained as part of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, and by September 1776 both of those men had moved on.38

The first year of the revolution saw the British evacuate Boston but brought no quick end to hostilities for the Americans. Congress and Washington knew a well-trained army needed longer enlistments and greater continuity. The new regiments offered men contracts requiring three years or the duration of the war. Prodded by Washington, the Continental Congress developed and implemented a plan to build a national army of 26 regiments for the 1776 campaigning season, and later 88 infantry regiments for 1777.39 As the Continental Army restructured to deal with the changing circumstances, the significance of the contributions of the first company commanders was overshadowed by the larger and grander events of 1776 and beyond. The events of 1775 — diplomatic, informational, military, and economic — are fundamental to understanding how the American Revolution unfolded.40 The U.S. Army and historians should not overlook the national army’s modest beginnings. Collectively, these 13 company commanders recruited, organized, trained, and led into combat the first 1,000 Soldiers to serve in America’s first national army. These men not only embraced the “Spirit of 1775,” they lived it. Below is a brief summary of the men and their revolutionary service.

Maryland

Maryland’s two companies were recruited in Frederick County (then the entire western portion of the state); both Cresap and Price mustered into service on 21 June at Frederick:

Michael Cresap served until his death caused by an illness on 18 October 1775; Moses Rawlings then assumed command of his company. Cresap was a well-known trader and land developer living on the Maryland frontier. He served as a militia captain during Lord Dunmore’s War and was present at the Battle of Point Pleasant (Ohio) in 1774 prior to his appointment to command one of Maryland’s rifle companies. He is interred in Trinity Church Cemetery in New York City and his home, the Michael Cresap House, located in Allegany County, Md., was listed on the National Registrar of Historic Places in 1972.41

Thomas Price served with his company until January 1776 and was promoted to major serving in Smallwood’s Maryland Regiment throughout 1776. He then took command of the 2nd Maryland regiment during December of 1776. His regiments saw action during the Siege of Boston, the New York Campaign, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. He resigned in April 1780 and died in Frederick, Md., in May 1795 at age 62.42

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania’s nine companies represent manpower contributions by seven northern and western counties. Pennsylvania’s company commanders appointed on 25 June 1775 include:

James Chambers hailed from Cumberland (later Franklin County); he eventually received a promotion in March 1776 and went on to serve as the lieutenant colonel of the 1st Continental Regiment, later designated 1st Pennsylvania Regiment (the reorganized Thompson’s Rifle Battalion). He was advanced to colonel of the 10th Pennsylvania in March 1777 and served only two months with the 10th and returned to command his old regiment, the 1st Pennsylvania. His units participated in the Siege of Boston, the New York Campaign, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine (where he was wounded on 11 September 1777), Paoli, Germantown, and Monmouth. He retired on 17 January 1781; he died at age 61 on 25 April 1805 and is interred in Falling Spring Presbyterian Church Cemetery, Chambersburg, Pa.43

Robert Clulage was from Bedford County and served through the reorganization of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion from the 1st Continental Regiment to the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment. His units participated in the Siege of Boston and through the New York Campaign until his resignation on 6 October 1776.44

Michael Doudel (Dowdle) hailed from York County, including portions of modern Adams County, and served for only two months after his company joined the Army at the Siege of Boston, resigning on 15 October 1775 because of poor health.45

William Hendricks and his company were from Cumberland County and served at the Siege of Boston for a month before making the incredibly difficult expedition to Quebec under Colonel Arnold’s command (September to November 1775). He was killed in the assault of Quebec on 31 December 1775. Along with Captain Hendricks, two enlisted men were killed and 59 men were captured, including 2nd Lieutenant Francis Nichols.46

John Lowdon hailed from Northumberland County, which then included portions of modern Union County. According to Francis B. Heitman’s Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April 1775 to December 1783, Lowdon served in the Quebec Campaign in the force advancing on Quebec via the Hudson River Valley and was wounded at Montreal on 12 November 1775. This appears inaccurate because only two companies of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion participated in the Quebec Campaign (Hendricks and Smith). He may have been wounded on 9 November 1775 at Lechmere’s Point, Cambridge. He apparently survived his wounds and returned home to Northumberland County where he obtained a warranty deed on 300 acres of land in May 1785. His name continued to appear on tax lists through 1798, likely the year of his death.47

Abraham Miller was from Northampton County and served as a regular for only three months after his company joined the Army at the Siege of Boston, resigning 9 November 1775. He served in the Pennsylvania militia in 1776, died in 1815 at age 80, and is interred in Elmira, N.Y.48

George Nagel was from Berks County and served with his company until he was advanced to major in the 5th Pennsylvania on 5 January 1776. Transferred to the 9th Pennsylvania, he served as lieutenant colonel and commanding officer (no colonel assigned) from May 1777 to January 1778 when he was promoted to colonel and transferred to command the 10th Pennsylvania. His units participated in the Siege of Boston, the New York Campaign, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. He retired on 1 July 1778 when the 10th and 11th Pennsylvania Regiments were merged, eliminating a colonel’s billet. He married Rebecca Lincoln, who was the sister of President Lincoln’s great grandfather; he died in Reading, Pa., in 1789 at age 53.49

James Ross, from Lancaster County, served through the reorganization of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion into the 1st Continental Infantry and subsequently served as a major in both the 1st Continental Regiment and the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment. His units participated in the Siege of Boston, the New York Campaign, Trenton, Princeton, and Brandywine. He resigned on 22 September 1777, 11 days after the Battle of Brandywine.50

Matthew Smith and his company served at the Siege of Boston for a month then made the march to Quebec under the command of Colonel Arnold. Smith survived the Quebec Campaign because he was absent at the time of the assault, likely ill as were 200 other members of Arnold’s force. During the 31 December 1775 assault, seven men of his company were killed and 35 captured. After returning from Canada during 1776, he served as major and later lieutenant colonel of the 9th Pennsylvania. His units participated in the Siege of Boston, the Quebec Campaign, Brandywine, and Germantown. He resigned on 23 February 1778 while his regiment was at Valley Forge to serve on the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania (1778-1780, representing Lancaster County). He served as Prothonotary (modern clerk of courts) of Northumberland County from 1780-1783 and died in 1794.51

Virginia

Daniel Morgan entered service on 22 June at Winchester, Frederick County, and was a veteran of significant frontier service including Braddock’s Campaign (1755) and Lord Dunmore’s War (1774). Serving at the Siege of Boston for a month, he led three companies of riflemen on the march to Quebec under the command of Colonel Arnold. He was captured in the attack on Quebec on 31 December 1775. Most of his company was killed, wounded, or captured in that assault. Morgan was later paroled and appointed colonel of the 11th Virginia in November 1776; the regiment was designated the 7th Virginia in 1778. He successfully commanded a task-organized rifle corps in the Hudson River Valley, contributing significantly to the American victory at Saratoga in 1777 and returning to Washington’s main army in time for action at Whitemarsh. After Monmouth, he resigned because of Anthony Wayne’s promotion to brigadier and command of a light corps, an assignment for which he was more qualified. At the insistence of General Horatio Gates, Congress appointed him a brigadier general in October 1780, and he commanded half of the southern army at Cowpens in January 1781, where he soundly defeated a British force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. After the Revolution, he represented Virginia in the United States House of Representatives and died in 1802.52

Hugh Stephenson formed his company in Mecklenburg (now Shepherdstown, Berkeley County, and now West Virginia), mustering into service on 21 June. He previously served as a company commander during the French and Indian War; Washington thought highly of his abilities. He was promoted in June 1776 to become the first colonel (June-September 1776) of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, an Extra Continental regiment because of its two-state composition. His units participated in the Siege of Boston and the initial phases of the New York Campaign; his command of the regiment was short-lived because he died in August or September 1776 in his home county while recruiting to fill his regiment.53

By December 1776, 18 months after the formation of a national army based around 13 rifle companies, all 13 original company commanders had moved on. Cresep, Hendricks, and Stephenson were dead; Lowden, wounded, left the army; Clulage, Doudel, and Miller resigned; Ross and Smith were majors (Ross with the 1st and Smith the 9th Pennsylvania); Chambers and Nagel were lieutenant colonels (Chambers with the 1st and Nagel the 9th Pennsylvania); Morgan and Price commanded regiments (Morgan the 11th Virginia and Price the 2nd Maryland).

Soldiers and all Americans should embrace the modest beginnings of the U.S. Army on 14 June 1775 and pay tribute to the first 13 company commanders who stepped forward to lead America’s first rifle companies. As an institution, the U.S. Army should seriously consider teaching each Soldier about the first 13 rifle companies to help instill an appreciation for the heritage associated with service to the ideals of 1775 applicable in today’s contemporary operating environment. Selfless service, to the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, is as applicable today as in 1775. Efforts to instill basic knowledge about the modest beginnings of the U.S. Army, explicitly linked to the formation of the initial 13 rifle companies, may pay handsome rewards in creating a common heritage and simple theme that every Soldier is first a rifleman. Today’s operating environment requires every Soldier be proficient with his rifle. Soldiers have a proud heritage that must be linked to the American military traditions emanating from the members of the first national army and its first 13 rifle companies of 1775.

Notes

1 Robert K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, 1983), 4-20.

2 John W. Wright, “The Rifle in the American Revolution,” The American Historical Review, 29 (1924): 293-299.

3 Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume II (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905), 89-90.

4 Ford, Journals, 89; Arthur S. Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold’s Army (NY: Savas Beatie, 2008), 291; Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 23.

5 Thomas Lynch Montgomery, ed., Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, Volume II, (Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company, State Printer, 1906), 4; Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold, 44-46.

6 Ford, Journals, 90.

7 Ibid., 104; Wright, Continental Army, 5.

8 Ford, Journals, 173; Wright, Continental Army, 25-26.

9 Ford, Journals, 100.

10 John Blair Linn, ed., Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution, Battalions and Line. 1775-1783, Volume 1 (Harrisburg, PA: L. S. Hart, State Printer, 1880), 3-4.

11 Theodore Thayer, Pennsylvania Politics and the Growth of Democracy 1740-1776 (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1953), 8.

12 Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M246, 138 rolls).

13 Army Lineage Series, Field Artillery, Part 2, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2010), accessed 20 December 2012, http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/060/60-11_pt2/CMH_Pub _60-11_pt2.pdf.

14 Wright, Continental Army, 51, 93, and 157.

15 This attitude is reflected in the motto appearing on the first regimental flag of the 1st Continental Regiment (the new designation of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion) “Domari Nolo”, translated from Latin as “I will not be subjugated.” Accessed 21 December 2012, http://www.1stcontinentalregiment.org/docs/Flag-2.pdf.

16 David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 363-379.

17 John K. Mahon and Romana Danysh, Army Lineage Series, Infantry, Part I: Regular Army (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1972), accessed 22 December 2012, http://www.history.army.mil/books/Lineage/in/infantry.htm; Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, 5.

18 Kenneth Roberts, March to Quebec, Journals of Members of Arnold’s Expedition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1946), 506-508; Luther Reily Kelker, History of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, With Genealogical Memoirs, Vol. I (NY: Lewis Pub. Co., 1907), 152; Tucker F. Hentz, Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment 1776-1781, Insights from the Service Record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 2007), accessed 20 December 2012, http://www.vahistorical.org/research/tann.pdf; Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, 24.

19 Roberts, March to Quebec, 506-508.

20 Hentz, Unit History, 3; Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, 24.

21 Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, 6.

22 Roberts, March to Quebec, 469; Linn, Pennsylvania in the War, 5.

23 Dr. James Thacher, “Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War from 1776 to 1783,” accessed 27 August 2009, http://www.americanrevolution.org/thacher.html.

24 Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, 6; Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold, 48.

25 Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, 6; Roberts, March to Quebec, 508-509, indicates Simpson was wounded on 3 September and died the next day; Franklin Ellis, History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania: with biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1883), 40, indicates the date of Simpson’s wound as 28 August with his death on 29 August.

26 Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold, 29-30 and fn 23, 286.

27 Roberts, March to Quebec, 510; Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold, 48-49.

28 Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, 28.

29 Roberts, March to Quebec, 199.

30 Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold, 217-271.

31 Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan.

32 Ibid., 214-215.

33 Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution, Volume I, (1859), Lechmere’s Point, accessed 20 December 2012, http://www.historycarper.com/1775/11/23/lechmeres-point.

34 David L. Valuska, “Thompson’s Rifle Battalion,” Continental Line Newsletter, Fall 2006, accessed 21 December 2012, http://www.continentalline.org/articles/article.php?date=0602&article=060204.

35 Hentz, Unit History, 5; Wright, Continental Army, 259; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April 1775 to December 1783 (Washington, D.C.: The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co., 1914) 177.

36 Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 25.

37 Hentz, Unit History, 4-5.

38 Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 26.

39 Wright, Continental Army, 48, 92.

40 Kevin Phillips, 1775 A Good Year for Revolution (NY: Penguin Group, 2012).

41 Heitman, Historical Register, 177 and Hentz, Unit History, 4-5.

42 Heitman, Historical Register, 452; Hentz, Unit History, 2-5.

43 Heitman, Historical Register, 149; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 22.

44 Heitman, Historical Register, 161; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 22.

45 Heitman, Historical Register, 201; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 22.

46 Heitman, Historical Register, 285; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 22-23.

47 Heitman, Historical Register, 359; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 23, 25.

48 Heitman, Historical Register, 392 and Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 23; Ancestry.com, accessed 30 December 2012, http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/13657802/person/12070112389.

49 Heitman, Historical Register, 474; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 23, 124; Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M246, 138 rolls) War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93, National Archives, Washington. D.C. Roll 83, Pennsylvania, 9th Regiment, 1777-1778, Folders 36-1 to 36-6; Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, Series 5, Vol. III, 393-4; Ancestry.com, accessed 30 December 2012, http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/6340412/person/-948985970/story/61ac6b51-593a-460c-9494-a4dadfedd831?src=search.

50 Heitman, Historical Register, 474; Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 23.

51 Heitman, Historical Register, 505-6; Revolutionary War Rolls, Roll 83, Pennsylvania, 9th Regiment Folders 36-1 to 36-6; Godcharles, Matthew Smith, 53-54. Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, Vol. XI, (Harrisburg: Theo. Fenn & Co., 1852) 502 and 618; Ibid., Vol. XII, 127, 148 and 221-2.

52 Heitman, Historical Register, 401; Hentz, Unit History, 4.

53 Heitman. Historical Register, 518; Hentz, Unit History, 2; Danske Dandridge, Historic Shepherdstown (Charlottesville, VA: The Michie Company, 1910), 349.

LtCol (Retired) Patrick H. Hannum, USMC, is an associate professor at the Joint and Combined Warfighting School, Joint Forces Staff College, National Defense University in Norfolk, Va. During his 29-year active-duty career, he served in all four Marine divisions including service as commanding officer, Combat Assault Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, Okinawa, Japan, and eight years of joint assignments. He has a bachelor’s degree in social science from Youngstown State University, a master of military art and science degree from the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College, and a master’s degree in education from Old Dominion University.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print