Developing a Training and Ready SFAAT

LTC Jared L. Ware

A Soldier with the 1st Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division gives a class on weapon handling toANA soldiers at Combat Outpost Fortress in Kunar Province, Afghanistan, on 12 March 2013. (Photo by SGT John Heinrich)

“The military advisory mission has become a key component of U.S. military operations — for the Army in particular — and we need to be good at it.”

— COL Marc D. Axelberg1

The purpose of this article is to provide a basic framework for developing a trained and ready security force assistance advisor team (SFAAT) based upon recent operational and training initiatives conducted by one battalion’s SFAATs.

In early 2012, the 30th Engineer Battalion at Fort Bragg, N.C., was tasked by XVIII Airborne Corps to develop an SFAAT to deploy in support of operations in Afghanistan. Since that initial request, the battalion has trained and deployed one SFAAT, activated a second SFAAT, and conducted two mission readiness exercises (MRX) at the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) at Fort Polk, La. Additionally, the battalion provided a robust observer controller/trainer (OC/T) team to the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, Calif., for an Infantry brigade combat team (IBCT) security force assistance brigade (SFAB) rotation enabled with a construction effects engineer battalion.

From a battalion-level perspective, it is imperative to understand the roles and missions of the SFAAT because that capability is the linkage between a brigade combat team and its Afghan military counterparts. Moreover, any mission set will be easier to achieve with Afghan partners if the SFAAT is trained, integrated, and operating at a high degree of competence.

The SFAAT individual selection process, the individual training program, and a full team-level MRX provide a strong foundation for the certification and employment of SFAATs. An SFAAT’s success is due in large part to the emphasis placed on SFAAT operations by its higher headquarters. An SFAAT’s effectiveness is a direct function of the quality of the individuals selected, their training certification, and their employment as a distinct and integrated team once in theater. Since most SFAAT descriptions include “advise, coach, and mentor,” it is necessary to select members who are confident and comfortable conducting those tasks at both the individual and collective levels.

In his December 2011 Small Wars Journal article “Combat Advisor Unit for Afghanistan Transition,” Morgan Smiley discussed that augmenting these types of teams with field grade officers as the lead advisors allows for the deployment of cohesive teams with the rank and experience necessary to deal with Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) leaders, and it mitigates a clumsy manning process by creating a force structure primarily focused on advising and enabling the ANSF. Our unit selected strong field grade officers to lead the teams and combat-tested and experienced NCOs to serve in the SFAAT. To increase the overall credibility of the SFAAT with its in-theater counterparts, all advisors developed proficiency in basic combat skills to include warrior skills and survival skills. Since these skills are critical to an advisor due to the isolated and independent nature of the mission, advisors were expected to refresh them during the various phases of pre-deployment training.2 Once baseline proficiency is gained in these skills, it is imperative to test the SFAAT during an MRX to validate individuals’ skill sets, collective training tasks, and team dynamics under a realistic operational environment.

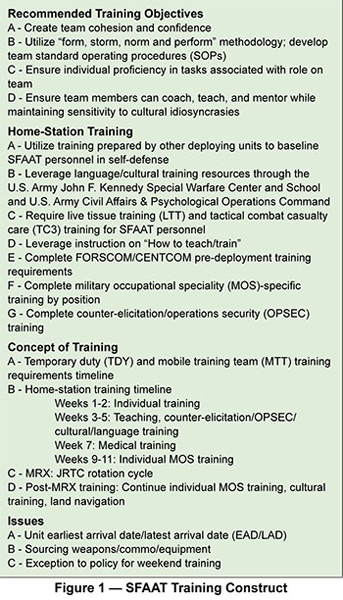

SFAATs from the United States and other Northern Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member organizations have identical minimum training requirements. This is directed by the commander of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and is further outlined in memorandums from the commanders of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) and Allied Joint Force Command Brunssum (JFCB) to the regional commands (RCs) and headquarters (HQ), ISAF. The U.S. Army, U.S. Marines, and NATO countries all conduct SFAAT certification in three defined phases. Although the type and magnitude of training with respect to each phase may slightly differ, there is commonality in the training topics. These topics include individual and collective combat skills training, advisor training, and an MRX for final certification. Figure 1 is an example of what our battalion used for its SFAAT training construct.

A certifying team-level MRX is vital to validating the strength, skill, and credibility of the team prior to its deployment. In his article discussing mentoring ANSF units, Canadian Lieutenant Colonel (now Brigadier General) W.D. Eyre stated, “Mentoring efforts and advice will fall on deaf ears unless the ANA (Afghan National Army) sees the source as being credible.”3 After serving as the senior engineer OC/T at NTC during the 13-01 SFAB rotation, the aspect of credibility became more evident to me with respect to any SFAAT. This rotation for the 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division included two National Guard brigades reorganized into 64 separate SFAATs. The training format at NTC followed a similar pattern as conducted at JRTC. Current training regimens, particularly those at the training centers, rely heavily on situation training exercises to examine a potential advisor’s situational response in a particularly complex environment. This is important to training advisors because situational training exercises are valuable in assessing responses from individuals in new and difficult situations, particularly in the context of another culture.4 Having a cadre of personnel to evaluate each SFAAT, as well as relevant scenarios with realistic role players, provides the most optimal environment for determining the strengths and shortfalls of any SFAAT undergoing the training.

Given the SFAAT training framework with a JRTC rotation, it is reasonable to expect that the training principles would provide any team with the baseline capabilities to operate effectively in theater. With this framework, the XVIII Airborne Corps’ SFAAT team from the battalion qualified as the top SFAAT of the 25 participating SFAATs during that specific JTRC rotation. However, to achieve mission success, it is incumbent upon an SFAAT to complete all individual training certifications and complete a credible, unbiased MRX (either JRTC or NTC) to fully prepare for the complexities and challenges of SFAAT operations in theater. Even with a solid training and certification program, areas for improvement still exist, particularly for a SFAAT once it arrives in theater and begins its mission for its higher headquarters and with its ANSF partners. LTC Joshua Potter, a former advisor, wrote, “In order to support their prescribed role, planners must take careful design in the organization and resourcing of military advisors either employed as a unit or as individuals.”5

The topic areas listed below are mainly based upon the feedback I have received with respect to the initial SFAAT’s employment once in theater. Although the observations are limited in scope, I found the same trends were common in discussions with previous SFAAT advisors, the SFAAT in theater, and with OC/Ts during the NTC rotation:

Mission — In theater, key leaders at the brigade level tend to lack a sophisticated understanding of the SFAAT’s mission and role. This leads to the inability to correctly employ and utilize the SFAAT’s full capabilities. This has resulted in certain team members being assigned to perform traditional staff functions instead of their individual SFAAT role. For example, one member of the SFAAT was assigned to the brigade engineer cell and one member was assigned to the governance stabilization and transition team (STT). This broke the SFAAT team integrity model, degraded its overall effectiveness, and impeded the ability of the SFAAT to establish a high level of rapport with ANSF counterparts. During the NTC rotation, leaders within the BCT were reassigned from their modified table of organization and equipment (MTOE) position to fill SFAAT positions without the requisite individual training prior to their assignment into an SFAAT. This created confusion as to what role the individuals would assume within the SFAAT, as they were not fully trained to take on the various tasks required within the SFAAT.

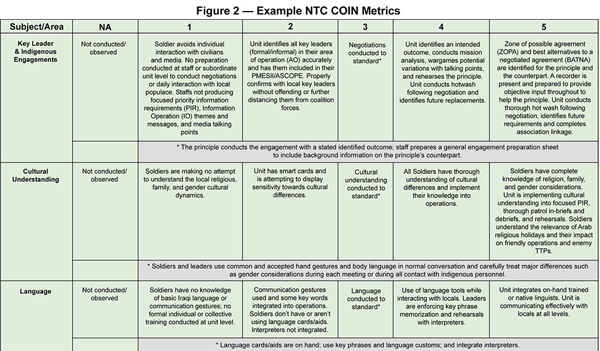

Metrics — The reporting of credible counterinsurgency (COIN) metrics requires proper SFAAT-led and SFAAT-reviewed assessments. Credible metrics cannot be properly evaluated at the brigade level without a credentialed SFAAT in place. In certain instances, the in-theater brigade reported higher levels of ANSF preparedness than that evaluated by the SFAAT. For example, ANA companies had leaders who were not capable of performing basic military decision-making process (MDMP) tasks or troop leading procedures. However, it was being reported that these units were prepared for unilateral missions based solely upon individual task assessments vice collective-level assessments as defined by COIN metrics evaluated by the SFAAT. Moreover, it is incumbent upon the SFAAT to immediately establish its credibility with both its higher headquarters and its ANA counterpart. During the recent NTC rotation, I viewed a combat outpost defense in which the SFAAT and ANA counterparts (role-played by Fort Irwin Soldiers) had not even met prior to the defensive operations, thus skewing any type of credible COIN assessment of the subsequent operations. This led to various interpretations of the overall readiness of the ANA unit, reduced the initial credibility of the SFAAT, and led to a “metric’s mismatch” between the SFAAT and its higher headquarters. (See Figure 2)

Sustainment — As a non-MTOE unit, the SFAAT lacks a baseline logistical support package required to properly deploy and sustain itself until employment into theater. The SFAAT is entirely dependent upon its higher headquarters and outside resources for all sustainment activities. Without a well-established command and support relationship, the SFAAT simply cannot function outside of its assigned operational role, and even then it is only for a limited duration due to a lack of sustainment. The advisor team still requires communications, logistics, and force protection support, and the BCT commander must rely on the advisors to provide the input required for coordination of joint patrols and daily actions of the advised force.6 One example from the SFAAT in Afghanistan is that upon arrival and link up, its higher headquarters provided the team four vehicles, three of which were non-mission capable. The SFAAT does not have organic maintenance support and lacks a funding source to purchase vehicle parts or contracted services. A major issue at NTC was the availability and fielding of Blue Force Tracker and communications equipment to the various SFAAT teams and any subsequent logistical support to the communications equipment. Given the expanse of sustainment challenges to support multiple SFAATs, it is recommended that any BCT deploying in support of an SFAB mission strongly consider not reorganizing its organic brigade support battalion (BSB) into SFAATs, as the BSB is vitally important to the overall sustainment of all SFAATs from the BCT. The advanced logistical support provided by the BSB is the key to sustaining a BCT’s worth of SFAATs in a brigade’s footprint.

Recommendations

- Ensure every person on the SFAAT completes all required theater training requirements and that the team itself conducts a credible MRX, preferably as an established team. The JRTC Advisor Academy provides premier training to SFAATs during training rotations. The program consists of language training, cultural training, key leader engagements (KLEs) with retired ANA, and understanding the advisor role in a deployed theater per FM 3-07.1, Security Force Assistance. When talking about his team, one SFAAT leader in a previous rotation remarked, “Security force assistance is the unified action to generate, employ, and sustain local, host-nation, or regional security forces in support of a legitimate authority.”7

- Building and sustaining team integrity is paramount to SFAAT operations. This allows for all personnel on the team to know their teammates are prepared and ready to assume their roles. It also allows individuals to learn one another’s strengths, as well as the areas that require additional focus, prior to linking up with ANSF counterparts. Regarding NTC Rotation 13-01, one battalion commander remarked that the NTC experience helped with the execution of their mission in Afghanistan because there were a lot of unclear things between the initial coordination efforts.8 It is important to build the team integrity during any training rotation, but it is equally important to sustain it into the deployment, as many valuable lessons were gained in the overall training framework. Building and sustaining team integrity will eventually prove successful in theater for the SFAAT.

- Establish peer-to-peer advisory relationships All SFAATs should be able to properly advise their ANA/ANSF counterparts at the command and staff levels, and ensure that the process occurs in parallel — in addition to vertically and horizontally. This includes sourcing SFAAT positions with personnel of the proper rank and experience level who can engage and advise counterparts at all levels. Personnel selected for advisory duties must be adept at the tasks and functions with which they are charged to train others and must possess the proper attributes to be effective advisors. Furthermore, it is important to provide advisor-specific training to each SFAAT member prior to having them mentor ANA forces.9 With a proper SFAAT structure in place, coupled with trained and vetted personnel, a more effective, accurate, and credible assessment of established COIN metrics can be attained, reducing ambiguity for any ANSF readiness assessments.

- Deploy cohort SFAATs that are either organic or assigned to a brigade prior to a deployment (brigade security force assistance teams). This would provide the teams with an established command and support relationship and a dedicated brigade-level staff to address any requirements. Moreover, it would address any mission and sustainment gaps as the brigade would have a dedicated SFAAT missions and the resources required to meet mission success. Additionally, allow the SFAAT team leaders time to influence pre-deployment training at Phase II training centers, develop mission specific TTPs, and prepare SOPs. This proved to be successful at NTC for the entities that followed the aforementioned training framework.

It would be presumptive to imply that the recommended solutions could be extrapolated to address all issues associated with developing and training SFAATs. However, the proposed recommendations can be applied to any future SFAATs and their specific training requirements with reasonable validity. By properly applying the training framework and the training principles, it can be reasonably expected that any SFAAT would have the baseline knowledge and skills to adequately perform its in-theater mission.

Notes

1 COL Mark Axelberg, “Enhancing Security Force Assistance: Advisor Selection, Training, and Employement,” U.S. Army War College Strategy Research Project, 22 March 2011, 27.

2 FM 3.07-1, Security Force Assistance, May 2009, 7-4.

3 LTC W.D. Eyre, “14 Tenets for Mentoring the Afghan National Army,” The Bulletin, Vol. 14, No 1 (March 2008), 1-9.

4 MAJ Brendan Cook, “Improving Security Force Assistance Capability in the Army’s Advis and Assist Brigades,” School of Advanced Military Studies monography, 10 May 2010.

5 LTC Joshua J. Potter, American Advisors: Security Force Assistance Model in the Long War, Combat Studies Institute Press, 2011.

6 Axelberg, “Enhancing Security Force Assistance.”

7 CPT Colby K. Krug, “When Combat Advising Equals Company Commander,” Engineer, January-April 2013, 40.

8 SSG Jennifer Bunn, “National Training Center Brings Change to 2-14 Infantry,” 24 October 2012, http://www.army.mil/article/89897/NTC_rotation_brings_change_to_2_14_IN/

9 MAJ Sean R. Pirone, “Security Force Assistance, Strategic, Advisory, and Partner Nation Considerations,” Naval Post Graduate School thesis, December 2012, 47.

LTC Jared L. Ware is currently serving as commander of the 30th Engineer Battalion, Fort Bragg, N.C. He previously served as program manager of Foreign Military Sales Construction, Multinational Security Transition Command - Iraq, J7 Engineering Directorate. LTC Ware graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., with a bachelor’s degree in human/regional geography. He has also earned master’s degrees from Missouri University of Science and Technology (engineering management) and Cranfield University in Shrivenham, England (defense geographic information). LTC Ware would like to thank MAJ Jermaine Walker and 1LT Dominic Sentero for their operational SFAAT perspectives and the Puma Team at NTC for support provided during Rotation 13-01.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print