Book Reviews

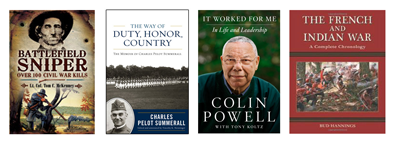

Battlefield Sniper: Over 100 Civil War Kills

By Lt.Col. Tom C. McKenney

England: Pen and Sword Books, 2009, 400 pages

Reviewed by LTC Keith Everett

This brutal Civil War story of Confederate scout-sniper Jack Hinson and his relentless, methodical killing of a probable 100-plus Union soldiers is told by Tom McKenney, a retired Marine lieutenant colonel. A Union horseback patrol captured and beheaded two of Hinson’s sons, George and John, and drove the point home that spies were not tolerated by impaling their heads on the gateposts to the Hinson plantation home early in the Civil War. This brutal action propelled the 57-year old father to kill as many Union soldiers as he could. Whether George and John were truly Confederate spies, guerillas, or just innocent hunters cannot be proved, but this is a clear example of how a thoughtless act can push a neutral bystander into becoming a motivated, relentless, deadly opponent. Hinson commissioned a .50 caliber sniper rifle and proceeded to kill as many Union soldiers as he safely could from a distance.

The rifle Jack Hinson commissioned for his sniper work is a fascinating story in itself. At 18 pounds overall, the heavy barrel required a rest of some sorts. The barrel was rifled, giving the bullet a nice spin for a more accurate shot. Through careful research, the author found the actual rifle, which now is in the possession of Judge Ben Hall McFarlin in Murfreesboro, Tenn. The rifle was passed down from MAJ Charles W. Anderson, who acquired the weapon after Hinson’s death and had discussed the markings on the rifle as evidence of his Union soldier kills. The author begins his book with Anderson’s written description of Jack Hinson and his discussion of these rifle markings; he does an admirable job in meticulously researching the history of Hinson and his family. McKenney blends facts with family stories that had been passed down through generations to put together a fascinating story. The story picks up around chapter four, with McKenney putting together some data on the .50 caliber rifle and ammunition used by Hinson that had been commissioned specifically for his new role as a sniper.

Although the author applies the myth of Southern slave relations as often enjoying “a mutual affection with their owners, who considered them part of the extended family,” he portrays the Hinson family as “kind and protective” slave owners with little or no evidence of this. The portion regarding Hinson’s slaves is a stark contrast to published autobiographical slave narratives of this time period. This depiction stretches credibility some, but there is a gap in the historical record to neither prove or disprove McKenney’s slant on the relationship between Hinson and his slaves. This is not a fatal flaw to the story because Hinson’s treatment of his slaves is a separate issue from the sniper story.

McKenney does a commendable job of weaving a fascinating story from the sparse facts he is able to collect over years of diligent research. He does the best he can to verify the accuracy of facts and then uses his military background knowledge to fill in the sizeable gaps in the Hinson family history with the probable history. The Jack Hinson story is a rich wartime story, and McKenney did a great job of researching and preserving it. After the historical background in the beginning chapters, the story picks up at an incredible pace and I found myself wanting to read more details about Hinson’s sniper activities during the war. This work is recommended to anyone interested in sniping and the weapons and tactics used in sniping. It is also a clear example of how thoughtless killings can create guerillas where there may not have been such before.

The Way of Duty, Honor, Country: The Memoir of General Charles Pelot Summerall

Edited and annotated by Timothy K. Nenninger

Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2010, 298 pages

Reviewed by BG (Retired) Curtis H. O’Sullivan

I found it hard to put this book down. It is a straightforward personal account of the life of a good Soldier — perhaps not a great one, but one who ranks high in our military. Charles Pelot Summerall was the eighth person to have the grade of full general (Washington in the Revolution; Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan after the Civil War; and Bliss, Pershing, and March in World War I). He was the 12th Army Chief of Staff, a post established in 1903, and the fourth to wear four stars in it.

Nenninger has added footnotes when needed for clarification and has left many pungent observations. Summerall was hard-nosed and had strong convictions. The names of some of those he disliked may have been deleted which is unfortunate; a fair number can be identified from the context by those familiar with the period though.

One of the striking things within this book is Summerall’s rise from poverty. This is strong evidence of the role West Point has played in providing opportunities throughout the country for all levels of society. The title of the book states the path for Summerall. The steps he took were not too unusual but led him to the highest position in his profession — from a junior officer in the Philippine Insurrection and the Boxer Rebellion to brigade, division, and corps commanding general in WWI.

My only regret is that there are no maps of those areas, but they’re not really essential to his story and weren’t in the memoir.

Other senior officers have gone on to later careers with the White House, State Department, etc., but Summerall’s time as president at the Citadel is special. He didn’t really leave the beloved Army during his tenure there from 1931-1953, when he was followed by Mark Clark.

The Way of Duty, Honor, Country is enough about his family and personal life to make this more than a military biography. It is a great story of a career during an era of dramatic change — not only for the Army but our society as a whole.

This is highly recommended for anyone with an interest in America and its Army from 1867 to 1953.

It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership

By Colin Powell

New York: HarperCollins, 2012, 304 pages

Reviewed by MAJ Kirby R. Dennis

Although he has been absent from the public arena for years, GEN (Retired) Colin Powell remains one of the most celebrated and esteemed public leaders of our time. In It Worked For Me, Powell effectively writes about lessons learned in life and in leadership in a tightly packed memoir that is highly readable. Although there are many written accounts on one of the most celebrated military leaders of all times — including his own autobiography My American Journey or the impressive Soldier by Karen DeYoung — readers should consider Powell’s latest work for its timely advice and perspective. Powell not only provides this advice with the persuasiveness and purpose of a retired four-star general, but also with a relaxed sense of storytelling that puts the reader at ease and makes for an enjoyable experience. Powell’s professional resume is as impressive as any public servant in recent memory. Whether it was as a junior officer advising the South Vietnamese Army, a White House Fellow, Corps commander, National Security Advisor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, or Secretary of State, GEN Powell was at the center of national security events throughout his life. This gives him unique license to write on the vital topic of leadership — and we all should listen.

For those who are familiar with Powell’s previous works, the opening chapter may seem a rehash of his famed “13 rules;” however, when considering his breadth of experience as a Soldier, military officer, or the nation’s leading diplomat, one reads these rules with a new appreciation for their durability and application. Simple, yet valuable lessons are contained throughout the book: Personal life outside of work is just as important as the one you lead at work; treat people with respect and dignity; trust in your subordinates; and bad news doesn’t get better with time. In the chapter entitled “Busy Bastards,” the reader gets a refreshing perspective that is often lost in today’s fast-paced environment. At the same time, Powell discusses the more sophisticated aspects of leadership in his chapter about the “spheres and pyramids” that exist within an organization and also illustrates the art of public speaking vis-a-vis the “five prominent audiences.” Powell expertly uses experience and storytelling to illustrate highly applicable rules, concepts, and ideas. The future military assistant will find a blueprint for success and the aspiring business leader a model for running constructive, efficient meetings. Throughout this informative and well-constructed account, Powell provides the reader with insight that is not only interesting but also incredibly useful.

Few would dispute that Powell was among the most strategically gifted military leaders of our time, and the foundation on which he succeeded was clearly rooted in the principles about which he writes. Even more impressive, the message and lessons apply equally to the sergeant, lieutenant, lieutenant colonel, or business executive. Perhaps the greatest lesson of all is found in the middle of the book when Powell answers his own question “what is a leader?” His answer is simple: “Someone unafraid to take charge. Someone people respond to and are willing to follow.” He goes on to say that leadership can be cultivated and taught over time, and that one can “learn to be a better leader. [But] you can also waste your natural talents by ceasing to learn and grow.” Powell continuously reminds us that we are humans trying to master the human endeavor of leadership. The aspiring leader should pick literature wisely — as there is much to choose from. In It Worked For Me, one will find proven lessons in leadership that are served with wit, humor, and good cheer. More importantly, Powell articulates these lessons in a manner that will undoubtedly aid leaders in their endeavor to learn and grow.

The French and Indian War: A Complete Chronology

By Bud Hannings

Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011, 344 pages, www.mcfarlandpub.com

Reviewed by Sarah Harden

Bud Hannings is an independent historian whose other works include Chronology of the American Revolution: Military and Political Actions Day by Day, Forts of the United States: A Historical Dictionary 16th Through 19th Centuries, The Korean War: An Exhaustive Chronology. Born in Philadelphia on 5 June 1942, Hannings was destined to become a great writer of history.

As a young man, Hannings joined the United States Marine Corps Reserve after high school. Later, he was elected to local office and served eight years as a commissioner in Pennsylvania. Always having been interested in history, Hannings finished writing his first work, The Eternal Flag, in 1979. Afterwards, he started writing a history of the American flag, but when it was rejected by a publisher, Hannings started his own publishing company in Glenside, Pa., called Seniram Publishing Incorporated (Marines spelled backwards). Hannings’s first published book, A Portrait of the Stars and Stripes, led him to realize the hardships an unknown publisher faces without national acknowledgement. He would have given up had he not remembered his drill instructors telling him that nothing is insurmountable for a Marine and that Marines never quit. Those inspirational words and his beliefs that countless military accomplishments and lost heroes were not being recognized accordingly led to his determination and success. Today, having written numerous additional historical works since his first, Hannings is a tribute to historians and to anyone interested in the historical events that helped shape the United States.

The French and Indian War: A Complete Chronology gives a very detailed, organized, and extensive chronological look at the conflict between Great Britain and France over which empire would rule North America. The French and Indian War, known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe, affected not only Great Britain and France, but also India, Africa, and the West Indies as more nations became involved. Prussia fought for control of Silesia against Austria in the Third Silesian War, another part of Europe’s Seven Years’ War, and once the Spanish joined and brought the war all the way across the Pacific to the Philippines, a world war had begun.

This book closely examines campaigns within the colonies, documents battles both on the land and at sea, follows Pontiac’s War in 1763, and focuses on military aspects. It also covers Britain’s failures to overcome France’s successes, and then Britain’s comeback and eventual victory. Additionally, Hannings describes the natives and how they introduced their savage warfare methods to arriving British troops as well as the Indians’ actions against the settlers, the settlers’ families, and the settlements. Another facet of this book is the information on individual units and men, and how many who served later became prominent naval officers, general officers during the American Revolution, and political leaders.

This immensely comprehensive work was created through research of various journals, reference libraries, state archives, papers, and historical societies. At some points during his writing process, Hannings even contacted European libraries for aid in identifying certain people. Lastly, in order to help readers better identify geographical locations while reading, Hannings deliberately uses familiar names, such as Missouri and Indiana, even though many North American locations during the 18th century were not yet the states we know today.

Hannings starts the chronology in 1748 to explain what led up to the start of the war campaigns in 1754, and he finishes in 1766 as the North American colonies began to think about an American revolution due to Britain’s tight rule. Each year is broken down into chronological sections by date, month, day of the week, and location. Most times, the dates are consecutive [i.e. July 15 (Sunday) 1759, July 16 (Monday) 1759, etc.], proving the amount of research Hannings had to do in order to write such a detailed work. To provide a concrete element to all of his facts, Hannings includes many sketches of people, events, and maps along with their descriptions and where he got them from throughout the pages of this book. The preface gives a complete rundown of what the reader should expect when reading, and the introduction presents events and many of the included peoples’ backgrounds leading up to their roles and involvement within the war. Appendix A lists “British Nobility of the War Era,” and Appendix B lists “Men Who Became Prominent Officers or Politicians in the American Revolution.”

Many times, a long chronological work can seem redundant, and The French and Indian War is no different. However, despite these occasional moments, this book is splendid for aspiring historians and history-buffs alike. Hannings sets out to give a detailed account of the French and Indian War, succeeding beautifully with this extensive chronological reference. Also, even though all of the events mentioned in this book cannot truly be explained or conveyed in just one volume, Hannings gives concise, yet detailed information and does not drone on and on for several pages about minor occurrences. This handbook is invaluable to students, teachers, and researchers. The easy-to-follow timeline and comprehensive appendices, bibliography, and index aid all readers in their understanding of the war. I would suggest The French and Indian War: A Complete Chronology to anyone interested in or needing to research North America’s French and Indian War, Europe’s Seven Years’ War, the involvement of other nations at the time, or the names of officers and royalty during the period.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print