Broadening from the Armor Branch Perspective

Over the past year, we at Armor Branch (Officer Personnel Directorate, Army Human Resources Command) have analyzed in detail the results from four promotion boards, four command selection boards, three schools boards and three separation boards. Without question, individual performance is the single most important factor in an officer’s selection.

Beyond performance, two more trends emerged from these boards: the role of continuity over time and the balance ofexperiencesin an officer’s career. This combination (clearly demonstrated in the most recent command and senior-service-college boards) shows the increasing importance of officers’ versatility to serve at any echelon and in any capacity in the Army.

The purpose of this article is to define these additional trends for Armor officers and share these insights with rating chains, mentors and individual officers to ensure we remain as competitive as possible.

Continuity

The first emerging principle from these boards is that an officer’s career is a continuum – training, education and experience integrated and compounding over time – much like a retirement fund increases in value through recurring investment and interest accrual. A shortfall in one area or more can cause the officer to reach a professional point of diminishing returns at an earlier-than-necessary time, in essence reaching a glass ceiling where he is unprepared for his future responsibilities. While this ceiling can certainly be broken, the officer’s contribution to the organization and individual performance may suffer initially as he defines the new environment and learns to operate in it.

Balance

The second principle is the balance of experienceswe should achieve over the continuum of a career. To prepare officers to serve at the highest levels of the military, we must offset their leadership experiences in line formations with appropriate operational, institutional, joint and enterprise-level assignments. Besides exposing officers to various facets of the Army and joint force, this approach provides breadth and depth to their experience and invaluable understanding and context for subsequent assignments, including the perspective gained working with different leaders and staff from multiple branches, services and agencies across the government.

As an example, serving as a lieutenant or junior captain in a battalion staff before attending the career course balances the officer’s experience as a platoon leader and executive officer with experience above the company level, well before he commands. In this example, the staff time provides two benefits. First, it better prepares the officer, through experience, for the education he will receive at the career course. Second, serving on staff also provides him a new perspective of battalion-level operations through daily interactions with subordinate commands, adjacent units, higher headquarters and multiple leaders across these formations. While no lieutenant or junior captain will claim to want staff time, and many will actively avoid it, this formative experience is essential to their future performance and utility in the Army. Career-course graduates familiar with staff processes are arguably much better prepared to immediately integrate into the staff and contribute when joining their new units.

As a branch, Armor leaders must be as equally capable of serving in strategic headquarters, running the enterprise Army and preparing to assume the mantle of national-level leadership in the decades ahead as they are of closing with and destroying our adversaries.

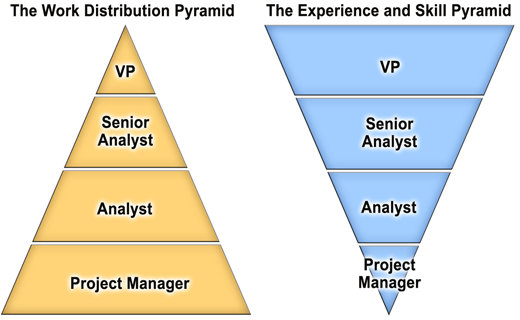

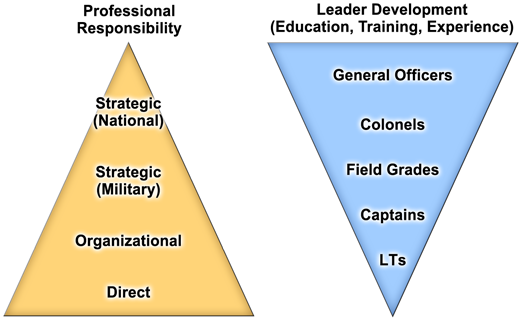

In the Jenkins Research Blog (https://jenkinsresearch.wordpress.com/), Dr. Richard W. Jenkins1 offers the model (Figure 1) of work distribution vs. skills and experience, looking specifically at marketing firms and their ability to meet client needs. Jenkins’ model illustrates the interaction between employee and client that most frequently occurs, with the highest work distribution at the least-experienced level. As employees gain experience and expand their skills, they grow in capability for the benefit of the organization (depth), and they must have a corresponding increase in their breadth of perspective. Employees must develop from client level to corporate level over the duration of their career, although they are further removed from direct interaction with clients as they grow in experience and responsibility.

Using Jenkins’ business model as a relevant example for an officer’s career and professional growth, we propose the military corollary in Figure 2 – professional responsibility vs. leader development, using the Army leader-development model of training, education and experience as the three pillars of leader development. As an officer develops professionally, he gains more responsibility and has an increasing understanding of the impact of his actions as a leader. At the same time, his progression pulls him further away from line formations, and his methods of achieving results must transition from directly leading to influencing as the number of echelons between the officer and the line increases.

While this may appear to be divergent, it is actually a convergence of experience, leader development and supervisory responsibility that is codified in doctrine in two distinct but complementary ways. In mission-command doctrine, we clearly expect leaders to understand the mission and intent two echelons higher in their chain of command because of the potential impact of their actions higher in the organization. Meanwhile, our training doctrine directs that leaders are responsible for training and developing two echelons down in their formations, ensuring the senior leader’s experience is best applied to preparing junior (direct and organizational) leaders to execute their requirements within the higher commander’s intent.

While key developmental (KD) positions distinguish officers in a relatively universal and comparative manner (e.g., company command) and highlight officers’ potential to selection boards as a frame of reference, every assignment counts over the duration of a career, KD or otherwise. To use a baseball analogy, every at-bat matters, whether scoring a run, getting on base or advancing a runner. Similarly, the sum of an officer’s performance andexperience tells a complete story about his ability to contribute where needed – whether in tactical formations, serving in an institutional assignment away from troops or in the Pentagon at the highest levels of the Department of Defense.

Generally, KD positions tie together, along with professional military education (PME), over time to prepare officers for subsequent KD and command positions. This compounding effect, where each future KD assignment builds on previous KD experience, thoroughly prepares our officers to lead within tactical formations by developing, refining and reinforcing their expertise and familiarity in these organizations. As officers progress beyond their captain KD time, however, we need to ensure they are prepared for service outside the familiar environment of the line. The logical progression of platoon leader, company executive officer, company commander, battalion or brigade S-3/executive officer, then battalion command, unequivocally ensures our battalion commanders are as prepared as they can be to effectively lead their battalions, develop their subordinate leaders and accomplish all missions.

However, KD positions do not explicitlyprepare officers for service at the strategic level by taking them outside their comfort zone and providing aninvaluablerange of experiences, also over time, in those unfamiliar environments. Serving in lieutenant and captain KD positions builds the foundational basis for officers, post-command, to prepare for future organizational and strategic responsibilities. In his article for Foreign Policy titled “The Bend of Power,” GEN Martin Dempsey assesses that “most problems around the world today do not have quick military fixes … [F]orce and diplomacy must work hand in hand.”2 And in the 2014 U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) commanding general’s leader-development guidance, GEN Daniel Allyn states that “it is imperative that we get leader development right; we must develop and retain our very best leaders” to develop “critically thinking, adaptive leaders ready to excel at the next level.”3

With the intent to fulfill KD time at the 18-month mark, plus or minus six months, we have the opportunity to place senior captains, majors and lieutenant colonels in multiple assignments (including joint positions) over their career after their company/troop command, field-grade KD or battalion/squadron command to achieve the developmental objectives of a broadened officer corps. In the proper context, most, if not all, the assignments available to KD captains, majors and lieutenant colonels afford these officers the opportunity to achieve the desired outcome of a broad range of experiences. Unfortunately, there are multiple interpretations of “broadening” that tend to lead officers away from, rather than to, broadening assignments.

Broadening

Questions we frequently get at Armor Branch are, “What is broadening?” and “Why do I need a broadening assignment?” There are two predominant perceptions that drive this line of questioning. The first perception is that broadening is, in effect, very narrow in scope – that broadening translates into one of a few types of specific assignments. In this first perception, some of the more frequent interpretations are assignments that:

- Offer the opportunity to pursue a funded advanced degree;

- Involve working on a senior leader’s personal staff; or

- Are joint, interagency, intergovernmental or multinational (JIIM).

While these types of assignments fall within the scope of broadening, they do not establish the limits of the broad range of experiences we are seeking for Armor officers.

The second perception is that broadening experiences do not prepare an officer for his next KD assignment and therefore do not contribute to his competitiveness for promotion or command. This second perception is amplified by the KD model applied, necessarily so, during the height of combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. As the Army focused on executing the current fight, officers were in KD assignments for multiple years, often stringing together KD in a continuous series of tactical assignments, sometimes even at the same installation and within the same formation. These officers, many now senior leaders, recognize their talent and leadership were directly applied to the current fight at the expense of shaping longer-term efforts at the strategic level.

This second perception does not stem from the leaders themselves, who executed magnificently to ensure success in current operations. Rather, this perception tends to come from junior officers who see their senior leaders as successful for lack of broadening – for their extended KD at multiple levels – and not the reality that they are successful despite their lack of broadening.

The benefit of these assignments may not be readily apparent to our junior officers as they look forward from their current duties to the different stages of a career. The paths that lead to lieutenant colonel, and potentially battalion command, don’t clearly traverse broadening assignments the way they do the sequence of KD positions. The benefitis generally apparent to an officer only after the experience, when he first applies what he learned in subsequent duties. Rather than wait for this moment of clarity to occur through hindsight, we need to deliberately develop our officers in anticipation of the future responsibilities they will have – before they fully understand what they gain from the assignments. Our responsibility is to provide the experience before it is needed.

To define the goal of broadening assignments, we start with the current definition (from Department of the Army (DA) Pamphlet 600-3, Paragraph 3-4b(2)(f)): “A purposeful expansion of a leader’s capabilities and understanding provided through opportunities internal and external to the Army … accomplished across an officer’s full career through experiences and/or education in different organizational cultures and environments ... to develop an officer’s capability to see, work, learn and contribute outside each one’s own perspective or individual level of understanding for the betterment of both the individual officer and the institution. The result of broadening is a continuum of leadership capability at direct, operational and strategic levels, which bridges diverse environments and organizational cultures.”

Within Armor Branch, we are operationalizing this definition to apply it to the detailed execution of our recurring assignment process. Our internal objective for Armor Branch with respect to broadening, or assignments outside of officers’ KD positions, is a broad range of experiences that provide officers fundamentally different perspectives of the Army as an element of strategic landpower.

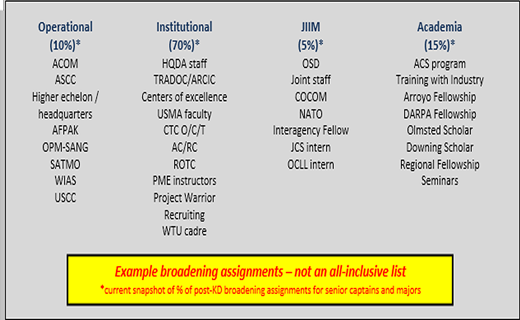

Through theseassignments, we allow the officer to place his prior experiences in the Army, as an operating force, into the larger context of the enterprise-level Army and the joint force. The goal of these experiences is that the officer is better prepared to provide operational and strategic leadership because he has gained understanding and context of the Army’s role in national strategy. Some examples of broadening assignments are listed in Figure 3.

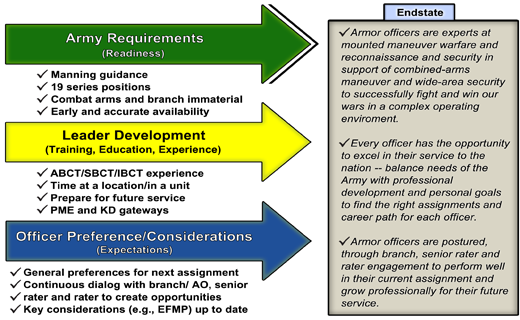

Placing officers in assignments like those listed in Figure 3 will set conditions for the transition we seek to facilitate – the point at which an officer with exceptional expertise at the tactical level, honed through training and operational experience, understands Army-level systems and processes, as well as comprehends the role of the Army in national strategy and the joint force. This is to ensure the Army is not only accomplishing current missions but is prepared for future requirements in a rapidly changing world. Figure 4 illustrates the transition point between professional responsibility and growth, where an officer leads and acts at the strategic level. This transition is our critical leader-development objective – that we actively prepare officers with sufficient breadth and depth of experience to meet the challenges of a highly uncertain and complex world.

Applying this framework to provide a broad range of experiences, we have implemented the assignment strategy depicted in Figure 5 for Armor Branch, with several key elements. First, as a branch, Armor will meet our mission – the Army requirements established by DA manning guidance and translated into assignments by the Human Resources Command’s Officer Readiness Division for each distribution cycle. Second, with officer, rater and senior-rater involvement, we will pursue assignments that professionally grow officers and prepare them for their future service. Third, we continue to work with Armor officers to balance Army requirements with leader-development opportunities and the individual’s preferences and personal considerations.

Together, these three lines of effort allow Armor Branch, rating chains, mentors and individual officers to achieve the endstate of the strategy. Besides working within the constraints depicted in Figure 5, we must remain responsive to changes to requirements due to unforeseen circumstances – a fact of life serving in the Army. Equally important in this strategy is individual-officer dialogue with his rater and senior rater – engagement that may result in disagreement as to the best developmental path for the officer. In the end, the officer himself is the only continuity in his career, and it is his individual responsibility to define and articulate his goals and preferences to both Armor Branch and his rating chain. Our collective goal in this strategy is to set conditions for the officer to perform in his next assignment while continuing his growth for future service.

Armor officers are highly sought throughout the Army and joint force because of our demonstrated versatility and effectiveness in tactical, operational and strategic positions. To meet the current and expected demand for Armor officers and ensure continuous professional growth, we will assign officers to the right opportunities, following the parameters outlined in this article. The familiar environment of line formations is highly rewarding but relatively comfortable compared to working in the C-Ring of the Pentagon as a member of the joint or Army staff; optimal developmental growth occurs not when the officer is comfortable in a familiar environment but when the officer is challenged in a complex and uncomfortable situation. To facilitate this continuous growth, our goal is to place Armor officers in multiple formations and echelons throughout the operating, generating and joint force, balancing their experience and training among tactical, operational and strategic organizations. These organizations will clearly benefit from having Armor officers in their ranks, and service in these assignments will increase the breadth and depth of experience in Armor branch for future requirements.

Close with and destroy. …

Key points

1. An officer’s career must be a continuum – training, education and experience integrated and compounding over time.

2. Balance experiences over the continuum of a career and ensure every assignment counts.

3. Leaders must be as equally capable of serving in strategic headquarters, running the enterprise Army and preparing to assume the mantle of national-level leadership in the decades ahead as they are of closing with and destroying our adversaries.

4. As officers progress, we need to ensure they are prepared for service outside the familiar environment of the line. We must develop expertise before it is needed.

5. Our internal objective for Armor Branch with respect to broadening, or assignments outside of officers’ KD positions, is a broad range of experiences that provide officers fundamentally different perspectives of the Army as an element of strategic landpower.

6. Place Armor officers in multiple formations and echelons throughout the operating, generating and joint force; balance their experience and training among tactical, operational and strategic organizations.

Notes

1 Dr. Richard W. Jenkins, “Why Teams Don’t Look Like Pyramids,” Jenkins Research Blog, June 3, 2010, https://jenkinsresearch.wordpress.com/2010/06/03/why-teams-dont-look-like-pyramids/.

2 GEN Martin E. Dempsey, “The Bend of Power,” Foreign Policy, July 25, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/07/25/the-bend-of-power/.

3 FORSCOM Leader-Development Guidance,North Carolina: HQ FORSCOM, Jan. 27, 2014.

Further reading

Army Doctrine Reference Publication 6-22, Army Leadership, Washington, DC: HQ DA, Aug. 1, 2012.

Robert C. Carroll, “The Making of a Leader: Dwight D. Eisenhower,” Military Review, 89:1 (January-February 2009), http://usacac.army.mil/CAC2/MilitaryReview/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20090228_art010.pdf.

DA Pamphlet 600-3, Commissioned Officer Professional Development and Career Management, Washington, DC: HQ DA, Dec. 3, 2014.

Erol K. Munir, “#Talent and Assignments, The Army’s Pentagon Problem,” The Bridge, Oct. 31, 2014, https://medium.com/the-bridge/talent-and-assignments-8c0882175d2a.

U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), The U.S. Army Operating Concept – Win in a Complex World, Fort Eustis, VA: HQ TRADOC, Oct. 31, 2014, http://www.tradoc.army.mil/tpubs/pams/TP525-3-1.pdf.

email

email print

print