Crisis Response: the East African Response Force in South Sudan

In the wake of Benghazi and the loss of four State Department personnel, U.S. leadership began to consider options for crisis response and determined that the Army possessed the capability to be a key contributor to the joint force’s crisis-response team. Crisis response is not and should not be the exclusive domain of U.S. Marine Corps’ Marine expeditionary units (MEU) and the Special-Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force (SP-MAGTF).

To overcome the tyranny of distance in Africa, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) directed Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HoA) to stand up a flexible company-sized response force and marry it to a U.S. Air Force C-130 unit stationed at Camp Lemonier, Djibouti. However, any Army unit, regardless of its equipment set, can execute crisis response when teamed up with the appropriate tactical airlift. In the near future, the Army and Air Force should work together to complement the Marine Corps’ MEUs to expand the reach of joint crisis-response forces to protect U.S. interests.

At U.S. Ambassador Susan Page’s request, the Army and Air Force’s East African Response Force (EARF) executed its first operational deployment Dec. 18, 2013. According to Juba’s regional security officer (RSO), Bob Picco, the EARF’s capabilities, location and speed made it his first choice to support his embassy when political fighting erupted throughout Juba, South Sudan. Prior to the EARF’s deployment, the embassy experienced significant skirmishing outside its walls, and long gun battles between Dinka and Nuer soldiers occurred throughout the South Sudanese capital.

Over the next four months, the EARF provided critical force protection, allowing the mission to stay open and supporting the evacuation of 400 U.S. citizens and 350 third-country nationals. A Marine security-augmentation detachment relieved the EARF April 20, 2014.

Training

Company B, 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, assumed the EARF’s ground-force mission from Company B, 1st Battalion, 63rd Armored Regiment, Dec. 14, 2013. Four days later, the company deployed 45 Soldiers to South Sudan. The company executed this mission as rapidly as it did because of a solid transition with 1-63 Armor; the training program conducted at Fort Riley, KS; and CJTF-HoA’s certification process once in theater. Fundamentally, the tactical requirements are not complicated. The EARF’s primary mission is a company defense. In a worst-case scenario, the EARF’s defensive mission transitions to a noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO).

The battalion and company trained both of these scenarios at home station. At Fort Riley, the brigade’s company training lanes incorporated all unified land operations’ mission-essential task list tasks for a combined-arms battalion.

During company training, each company executed the defense of an embassy and interacted with the ambassador, RSO and a host-nation security-force commander. During this lane, they reacted to the ambassador’s and RSO’s requests, hostile crowds, snipers and improvised explosive devices throughout the mission.

The capstone-training event saw the battalion execute a movement-to-contact to secure the embassy under hostile conditions using our tanks and Bradleys. Using Joint Publication 3-68 and 1-63’s after-action review (AAR) as our guidelines, the battalion executed a NEO of the embassy, with B/1-18 Infantry executing all actions on contact with the embassy’s staff and host-nation security forces.

These training events established the battalion’s foundation for our certification in the Horn of Africa.

CJTF-HoA certified the battalion’s response force during the relief-in-place with 1-63 Armor Dec. 6-8. B/1-18 Infantry, with a small battalion mobile command element, executed an alert, deployed and executed mission sequence. During this training event, the battalion received a threat stream and Embassy Emergency Action Committee (EEAC) meeting notes that highlighted State Department security “tripwires.” After simulating the approval process for deployment, EARF executed its N-hour sequence and loaded two C-130s for a short air movement, then deployed to the U.S. Embassy in Djibouti. Once on embassy grounds, the EARF integrated with the RSO’s staff, established operational and tactical communications and emplaced its defenses.

Throughout the mission, the EARF responded to multiple CJTF-HoA injects to drive home training on rules of engagement, crowd control and react-to-contact situations. After the CJTF J-37’s AAR, MG Terry Ferrell – then commanding CJTF-HoA and now commanding 7th Infantry Division – certified the EARF for operational employment.

EARF in Juba

After our transition of authority with 1-63 Armor Dec. 14, 1-18 Infantry tracked two deteriorating security situations in Juba and Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR). With no U.S. diplomatic presence in the CAR, the battalion staff focused its efforts on Juba. Supporting the staff’s mission analysis, 1-63 Armor had previously executed a reconnaissance of the U.S. Embassy in Juba. This gave the battalion invaluable insight into conditions on the ground in Juba to support our contingency planning.

From Dec. 15-17, the civil unrest and political violence systematically advanced the EARF’s alert posture and repeatedly altered our load plans for this mission. After receiving the final go/no-go briefing with MG Ferrell Dec. 18, the EARF went wheels-up from Camp Lemonier, Djibouti.

The security situation in Juba Dec. 18 could charitably be called uncertain. South Sudan had closed the airport to civilian traffic, and Juba had been under no-movement orders as well as a 6-p.m.-to-6-a.m. curfew since Dec. 15. Due to these conditions, the battalion actually deployed two EARF packages: one 45-man team via two C-130s and a second 45-man team via CV-22s. The embassy through Ambassador Page and its defense attaché (DATT), LTC Klem Ketchum, secured landing rights from the South Sudanese government, and the primary C-130 force landed successfully, but the CV-22 package returned to Camp Lemonier. Upon landing, the EARF secured the airfield with host-nation forces while the DATT and RSO evacuated 135 U.S. civilians, embassy staff and other nationals.

When both C-130s were loaded with evacuees, the EARF moved to the U.S. Embassy in RSO-provided vehicles. Ambassador Page met us outside her residence, welcomed our arrival, then immediately turned us over to the RSO for tactical employment.

CPT John Young, 1SG Michael Fulkerson and I executed a leader reconnaissance of the embassy’s residence and chancery compounds. Upon completion of our reconnaissance, Young, the RSO and the Marine security noncommissioned officer in charge set the company’s defensive positions.

We maintained a low profile on the embassy’s grounds, setting up reverse slope (wall) defenses, as opposed to maintaining sectors of fire outside the compound. We executed this defense based on our authorities to operate in-country and rules of engagement that limited our operations to securing just U.S. facilities in Juba. With the ambassador’s permission, we built defensive positions throughout both compounds that included sandbag fighting positions as well as building tanglefoot and pungi-stick obstacles on the embassy’s interior walls. Young integrated his efforts with the Marines and RSO’s diplomatic-security force.

The EARF did experience small-arms fire near two of our defensive positions, but we were not actively engaged or harassed by local security forces or nationals otherwise.

While the company focused on establishing its defense, the battalion command group established operational communications with CJTF-HoA. We deployed our secure Internet protocol router (SIPR), global rapid-response intelligence package (GRRIP), tactical satellite (TACSAT), Iridium, world cellphones and Blue Force Tracker nanodevices to maintain our communication links with our higher headquarters. One week later, we improved our operational communications by deploying a J-6 SIPR/nonsecure Internet protocol router access-points terminal, giving the ambassador secure videoteleconferencing communications.

The battalion evaluated the atmospherics in Juba based on three major criteria: the neutral-to-positive South Sudanese security force’s reception of the EARF; the positive popular response to our arrival; and the embassy’s physical-security posture. In our first situation report to CJTF-HoA, we stated that, based on current conditions, we could hold both compounds until relieved, short of a full combined-arms attack against the embassy. We attributed this environment due to the United States’ prominent role in creating South Sudan, in which Americans are generally highly regarded by South Sudan’s political leadership and population in general.

Over the next four months, the battalion supported Embassy Juba with physical security and secure mission-command links, and we rapidly learned to maintain embassy generators and facilities. The battalion, working directly with the EEAC, provided daily intelligence fusion from CJTF-HoA’s J-2, information exchanges with U.S. officers serving on the United Nations’ Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and our monitoring of South Sudanese nightly television. Our intelligence summary included the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD) best estimate on military capabilities and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) and anti-government force’s intentions.

A sergeant from Company B, 1-18 Infantry, manned the consular officer’s duty phones, helping locate and later evacuate isolated American citizens throughout South Sudan. We conducted daily reconnaissance of the city in conjunction with the RSO staff, staying abreast of the SPLA, police and Ugandan deployments in the city. During these missions, we assessed civilian traffic, lines at gas stations, open and closed shops, and the populace’s access to food and water.

We could not have sustained ourselves as well as we did without the embassy’s active support. Embassy Juba provided vehicles, housing, water, power and even Internet access for the entire force. This reduced the battalion’s logistics footprint considerably. Logistically, the EARF’s only consistent needs were Class I and mail.

The battalion rotated the EARF in late January 2014. Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1-18 Infantry, and its scout platoon relieved B/1-18 Infantry’s rifle platoon, allowing the battalion to reset the EARF’s Force Package 1 for future operations. HHC, 1-18 Infantry, maintained the EARF’s presence until relieved April 20, 2014, by a 21-man Marine security-augmentation unit detachment.

Understanding environment

This operation should highlight the need for continued development of Army/Air Force crisis-response teams to augment the sea services. It is a joint problem, not a service problem. This battalion is a strong advocate for continuing to build these missions and relationships with the Air Force – especially in light of Benghazi, Juba and even our recent deployment of Army forces to Eastern European countries.

The most challenging aspect in crisis response is the political environment: the United States’ national decision-making process and appreciation of the sovereign nation’s concerns and interests. Crisis response is foremost a strategic mission and not just an operational or tactical problem. It is a political decision that will demand a whole-of-government decision through principles and deputies committee meetings.

It was an eye-opening experience to provide tactical information as a battalion commander directly to the U.S. National Security Adviser during a principles meeting. I definitely appreciated Ambassador Page’s willingness to incorporate the battalion’s command group into her EEAC’s decision-making process, the State Department’s crisis-action-planning meetings in Washington and sidebar conversations asking for our operational and tactical input. We were truly a part of her team.

Understanding the political realities in which a future force operates will only help inform the DoD chain of command. By being so close to Ambassador Page’s decision cycle, we helped shaped CJTF-HoA’s planning efforts to support the embassy and the EARF.

The United States was a little bit lucky in South Sudan. Because our nation had invested heavily in South Sudan’s creation and economic support, Ambassador Page leveraged that investment into host-nation permission to allow the EARF’s deployment. This is critical because the EARF, in its current configuration, must deploy in permissive environments.

The embassy also helped navigate South Sudan’s sometimes-convoluted decision process and understand the key players in Dinka, Nuer and other significant ethnic groups. Ketchum and LTC Chris Pollard (incoming DATT) cultivated their contacts with the SPLA to gain access to the international airfield and develop SPLA intentions throughout South Sudan. They ensured continued access to the Juba International Airport that enabled EARF logistic operations.

Without this deeper knowledge of South Sudan, the EARF would not have been as nearly successful.

Key suggestions

A tactical commander must understand how to “work friendly” within the joint, interagency, intergovernmental and multinational (JIIM) team with particular regard to mission command. In Juba, we operated under the ambassador’s authority. This was Ambassador Page’s operation, not AFRICOM’s or CJTF-HoA’s mission. DoD supported the State Department. The 1-18 Infantry reported to CJTF-HoA for mission requirements and support, but we executed tactically under the ambassador.

Due to American and host-nation political concerns, this was the right way to control this mission. Our chain of command was Ambassador Page to the RSO, then to the EARF. We coordinated everything we did through the ambassador and RSO, and we kept CJTF-HoA informed of all we accomplished. To their credit, not once did the ambassador or RSO refuse a reasonable military request.

Crisis-response forces working with U.S. embassies need to know the difference between a State tripwire and a military decision point. Tripwires are not decision points. They are the embassy’s way to subjectively tell its story from the ground and are more closely related to a commander’s estimate. A typical military officer would assume that crossing Tripwires 1-9 would dictate a decision to be executed. This is not the case. Crossing a tripwire generates a discussion of actions that might be taken but not an actual decision. Future crisis-response forces supporting an embassy should expect key decisions involving the United States’ presence to be made in Washington.

Intelligence fusion is critical to success. The battalion enabled the ambassador’s situational awareness by linking the CJTF J-2, the embassy staff, the EARF’s operations and U.S. officers working in UNMISS headquarters together as one cohesive whole. The CJTF J-2 was quickly able to gain access to embassy human-intelligence reporting, UNMISS intelligence reports from their security battalions and EARF reconnaissance throughout Juba. This all helped build a unified common operating picture across the JIIM team. These operation summaries became the basis of State cables and DoD situation reports to the Joint Chiefs and National Security Council staff.

Operational and tactical risks are inherent in these operations. What makes it inherently difficult is the risk to the mission and risk to the force when conditions change unexpectedly. Commanders will have to underwrite both types of risk based on political and State Department decisions. It will be uncomfortable. According to the commanding general who succeeded MG Farrell at CJTF-HoA, BG Wayne Grigsby, we should all operate uncomfortably because it makes us better.

As an example of risk to the force in Juba, the embassy compounds are in downtown locations surrounded by residential housing and tall buildings. In an environment where the United States is not targeted, 45 Soldiers defending these locations is reasonable. If the threat had changed to overt harassment or targeting by host-nation security forces, the risk to the force and mission would have drastically changed as 45 Soldiers with small arms would be hard pressed to defend against that change in threat.

Conclusion

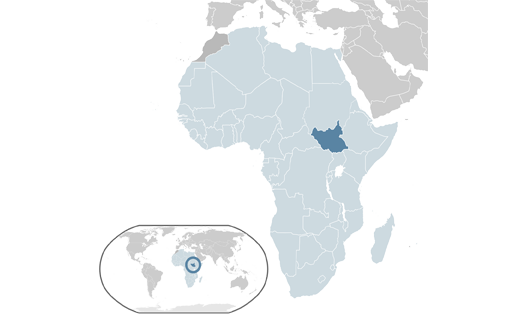

Africa is a huge continent. To put it in perspective, Africa’s land area equals the continental United States, China, India and most of Europe combined. The tyranny of distance and current U.S. basing is a major limiting factor for crisis response and is the primary reason to support the continued development of Army/Air Force response teams.

The Marines’ SP-MAGTF is a potent force that is basically an MEU-minus without ships and is based in Moron, Spain. The SP-MAGTF is responsible for northern and western Africa. Some of these locations will take a minimum of 24 hours just for travel. The EARF is currently responsible for East Africa and parts of Central Africa, and we can reach all designated embassies in less than 24 hours. In other words, the EARF complements the Marine Corps’ effort in covering U.S. responsibilities throughout the African continent. The Army/Air Force team can and should develop more forward-based forces to support U.S. requirements in Africa and other trouble spots throughout the world.

Any competent force can execute crisis response. Collective training and properly aligned resources build crisis-response capacity. Although I selected B/1-18 Infantry, a mechanized-infantry company, to execute this mission, I could have just as easily task-organized a tank company to execute this mission. The key requirements to execute this mission are a force that is trained to execute DoD and NEO collective tasks and is equipped with nonstandard communications equipment – for example, GRRIP, Iridium and TACSATs.

Finally, the Army force has to be paired with airlift. Right now, the EARF is paired with an Air Force C-130J. In the future, the air component should also have a vertical-lift capability: CV-22, MV-22, CH-47s or even UH-60s.

The EARF’s first real-world deployment is a definite success story. U.S. operations in South Sudan should generate a serious discussion between the Army and Air Force to develop crisis-response forces that complement, not replace, our sea service’s missions. As a point of fact, the SP-MAGTF supported EARF operations by providing vertical-lift evacuation options in case conditions changed on the ground. The SP-MAGTF also evacuated 25 U.S. Embassy personnel in mid-January. Crisis response is a joint mission and the U.S. Army, with our Air Force counterparts, need to be a part of it. No one service can cover the globe or Africa with just its own assets. email

email print

print