Painting the Picture: Cavalry Operations in a Jungle Environment(14 Lessons Re-learned at 25th Infantry Division’s Jungle Operations Training Course)

“To our men … the jungle was a strange, fearsome place; moving and fighting in it were a nightmare. We were too ready to classify jungle as ‘impenetrable.’ … To us it appeared only as an obstacle to movement; to the Japanese it was a welcome means of concealed maneuver and surprise. … The Japanese reaped the deserved reward. … We paid the penalty.” –Field Marshall Victor Slim in Burma, World War II (concerning the dark early days of the Burma campaign)

Picture the situation: The United States’ strategic focus is shifting from U.S. Central Command to U.S. Pacific Command, therefore 25th Infantry Division stood up the Pacific Contingency Response Force. The U.S. Army Pacific operating environment (OE) encompasses Southeast Asia, which is rife with environments that have traditionally been difficult in which to operate – many countries in the South Pacific region have thick jungle and/or rainforest terrain, which require a specialized skillset to ensure success in contingency operations. Based on these conditions, 25th Infantry Division’s commanding general directed the establishment of the Jungle Operations Training Course (JOTC) on Oahu, HI.

Since our unit is a mounted reconnaissance troop with the primary mission of being the “eyes and ears” of the brigade commander, it was necessary to send Apache Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, through JOTC to sharpen our skills on dismounted reconnaissance and security in restrictive terrain. This article describes a series of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that led to Apache Troop’s success conducting reconnaissance in a jungle OE and provides keys to shaping offensive operations for supported units.

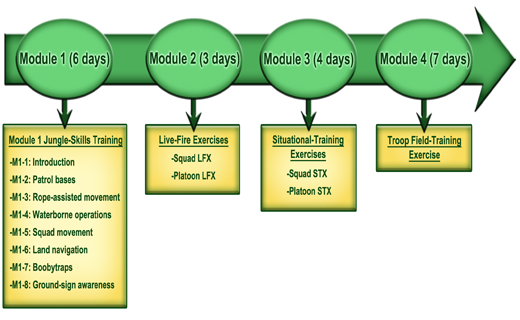

JOTC’s modules

JOTC’s goal is to prepare Soldiers and units from 25th Infantry Division, joint services and foreign partner nations to conduct successful operations in a jungle environment. The course is executed by a battalion task force and covers five weeks, with each troop/company executing a 21-day cycle divided into four modules.

Module 1 is six days covering individual jungle skills. This is a round-robin module covering the following tasks:

- Patrol bases;

- Rope-assisted movement;

- Waterborne operations;

- Squad movement;

- Land navigation; and

- Boobytraps.

This module serves as a way to introduce new TTPs that are fundamentally different from what any Cavalry unit has trained on since Vietnam. It also sets the stage for situations Soldiers and leaders will see in Modules 2 and 3. Platoons had the opportunity in Module 1 to develop standard operational procedures based on the new doctrine in preparation for field training in later modules.

Module 2 is three days where troops/companies execute both a squad and platoon live-fire exercise (LFX) focused on movement, actions on contact and fire-and-maneuver in a jungle environment.

Module 3 is four days of both squad and platoon situational training exercises (STXs) oriented on jungle doctrine learned in Module 1.

Module 4, the culminating training event, is a six-day company/troop field-training exercise (FTX) where the Cavalry troop executes reconnaissance forward of an infantry company on multiple objectives, conducts a reconnaissance handover and supports the deliberate attack with fires.

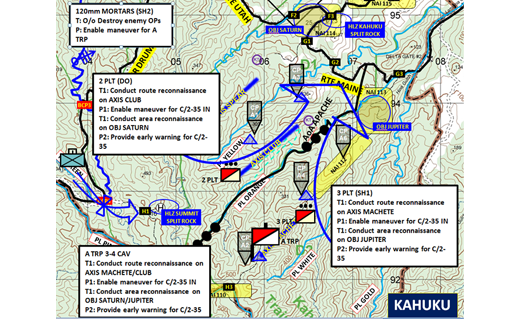

The troop STX (Module 4) consisted of one day of troop-leading procedure during a five-day FTX, where the mission was to conduct reconnaissance up to 48 hours prior to the battalion task force’s attack. Our key tasks were to identify the composition and disposition of enemy forces on two objectives, identify the most advantageous approach routes for follow-on forces, conduct a reconnaissance handover with the follow-on infantry company and provide overwatch during the attack, assisting with supporting fires if necessary.

The location of the training was Kahuku Training Area (KTA) in north-central Oahu. KTA’s terrain is characterized as severely restrictive rainforest, with steep gulches that often require rope-assisted movement across water obstacles and dense fern greenery that was virgin in most areas, often requiring trailblazing with machetes. Our primary mode of insertion was via UH-60 helicopter on a helicopter-landing zone (HLZ) out of visual and audible range of the objectives, from which scouts executed an approximately three-kilometer movement to the objective.

14 successful TTPs employed in executing jungle reconnaissance

Conduct early face-to-face coordination with the leadership of the supported infantry company. The most important element of the planning process to ensure mission success was the face-to-face interaction with the rifle-company commander during the task-force combined-arms rehearsal (TF CAR). This interaction, with scout-platoon leaders and the fire-support officer (FSO) present, was pivotal in ensuring we understood the infantry company commander’s intent for his assault, so that we as scouts could conduct reconnaissance to both paint the enemy picture and help shape the battlefield for his attack. This opportunity also served as the perfect opportunity to gain situational awareness of the fires plan for the follow-on unit in the event our scouts were required to observe fires on the objectives.

Commander’s reconnaissance guidance needs to address terrain equally as in depth as the enemy. Focus. Simply put, our mission was to find the enemy and show the infantry the best route to success. The latter point proved to require more in-depth analysis than first expected. Because of this, the focus of our commander’s guidance was twofold and enduring throughout the mission: Identify the composition/disposition of the enemy; and identify routes and key positions to facilitate the infantry company’s attack.

In the jungle, a wrong turn can lead to hours and, in extreme cases, days of delay. For this reason, terrain-focused reconnaissance was nearly as important as finding the enemy. This reconnaissance included deliberate identification of checkpoints (CPs) along a reliable route, hazardous terrain where special equipment was required and no-go areas. In addition, our accurate time/distance analysis resulted in an appropriately adjusted timeline for the infantry company’s movement so the leadership had maximum time for reconnaissance handover upon link-up. Concurrently, our scouts were identifying the disposition of enemy forces and, in particular, enemy weapons systems in accordance with the high-payoff target list.

Tempo. The first stage of our movement was through restrictive (deep gulch with river) terrain where enemy contact was not likely. During this period, our tempo was rapid and forceful. Once we gained the high ground, we ran the risk of being observed by enemy forces with optics, so we transitioned to stealthy and deliberate movement to avoid detection. We maintained this tempo for the rest of the operation.

Engagement criteria. Our engagement criteria allowed our scouts to engage only when we needed to avoid a hard compromise and to cover a break-contact. This was important, because with these criteria we were able to tailor our loads to carry little ammunition and no machineguns, giving our scouts the freedom to carry more water and meals-ready-to-eat to last 96 hours.

Conduct deliberate route planning. In an environment where a wrong decision on routes can lead to hours or days of observation missed, this part of the planning process needs to be deliberate and has several considerations. The first considerations in route planning are time and tempo – i.e., how much time is available, and how quickly does the commander need the information? For planning considerations, a 100-meters-per-hour pace can be expected for a platoon-sized element through dense jungle terrain. This pace not only accounts for difficult movement with necessary gear but also enables Soldiers to employ proper tactics.

Secondly, the route planner must find the most accurate map data available to properly plan for terrain. Attempt to find a map that was made using more than just aerial-satellite imagery. Correctly interpreting contour lines will be a priority; a relatively flat path can quickly transform into a non-navigable drop-off. Accurate map data combined with deliberate map reconnaissance will alleviate these issues. Traditionally, the best avenues in the jungle have been along ridges and across saddles, using low ground as a last resort (per Field Manual 31-30, Jungle Operations, October 1960).

Lastly, graphic-control measures are especially helpful in the jungle. Since visibility can be limited to 10 meters at times, plotting notable terrain features such as streams, hill, spurs, draws, etc., as CPs can help guide movement and confirm pace. Other useful navigation-control measures include recognizable backstops such as a body of water, a dominating piece of terrain or handrails such as ridgelines or streams.

Plan for the use of high ground during planned communication windows to ensure optimal transmission. Reliable communication in the jungle is integral to executing effective mission command and keeping higher headquarters informed with timely and accurate reporting. Effective communication on the move was often difficult because radio/telephone operators and forward observers could not extend their long whip antennae due to thick vegetation. For this reason, whenever possible we used communications windows and set up communications platforms on high ground. When the element became so far removed that standard communication was difficult, the platoons employed field-expedient antennae to ensure effective transmissions were maintained. Note: During planning, have the appropriate length of wire pre-cut for field-expedient antennae based on the desired frequency for ease of use after the line of departure (LD).

Employ an advance guard to proof the route and confirm maneuverability forward of the main body. Not everything in the jungle is as it appears on a map. A 20-foot decline in contour lines can quickly turn out to be a sheer rock face once on the ground. The incongruence between map data and actual terrain makes forward reconnaissance even more valuable in the jungle. The reconnaissance platoon or troop is the route surveyor for the infantry battalion, but who is the internal route surveyor for the reconnaissance element? The most effective method is to conduct a hasty route reconnaissance before moving the main recon body forward. The forward element’s TTPs will depend on mission, enemy, terrain, troops available, time and civil considerations – particularly on terrain and visibility. A technique we used was to send out a hasty leader’s recon of the planned routes to determine trafficability. This prevented larger elements from walking into situations where they had to backtrack and consume time.

Use long-range optics to develop the objective from standoff. The objectives rested at the base of two large spurs that ran down from the ridgeline to the northeast. Each platoon was tasked with conducting reconnaissance down one of the spurs that ran to the objectives to conduct assessments on insertion routes, while at the same time developing the enemy situation on the objectives. Initially the platoons used their dismounted long-range optics to develop the objectives from standoff, confirming/refining the fires plan and identifying intelligence gaps that needed to be filled by closer-in reconnaissance. From there, the platoons used a push-pull method with their sections, with one moving down the spur to conduct close reconnaissance while the other remained on higher ground to maintain eyes on the objective with a larger scope.

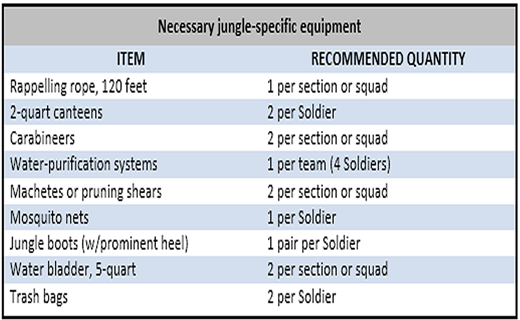

Carefully tailor combat loads. With every dismounted operation, individual Soldier loads are always a consideration for leaders. In some cases, leaders should consider the necessity for full combat power and personal protective equipment, depending on the length of the movement and the engagement criteria. For example, due to the difficulty of our infiltration, coupled with our guidance to avoid becoming decisively engaged at all costs, the troop decided not to take machineguns. We also did not take body armor. Both these elements decreased our survivability, but this risk was mitigated by ensuring our 120mm mortar section was constantly in supporting range in the event one of our platoons needed to execute a break-contact. The troop also took a minimum of personal ammunition – just enough to support a break-contact – to further lessen individual loads to allow Soldiers to carry more water.

When conducting long-duration operations in the jungle, “comfort items” should be a last priority. Mission-essential equipment and the minimum amount of gear to survive for the duration of the operation should be the only items considered in a Soldier’s packing list. Any extra space should be used for additional water storage.

Also consider adjusting the position of the Soldier’s sustainment pouches (relocate them from the sides to the rear) to reduce each Soldier’s profile so he can better avoid getting caught in dense vegetation. Careful consideration of the Soldier’s fighting load proved to be a force multiplier and helped the troop maintain a steady pace all the way to the objective.

Use personal camouflage to increase survivability. Scouts need to be able to infiltrate to observe the reconnaissance objective without being detected, and personal camouflage will play a major role in maintaining the required stealth. Camouflage face paint needs to be part of the packing list, inspected during pre-combat checks (PCCs)/pre-combat inspections (PCIs) and included in priorities of work. Also as a part of priorities of work, scouts in observation posts (OPs) not only need to be constantly improving their personal camouflage but also the camouflage of their position to prevent identification from above.

Training to conceal Soldiers and equipment from ground and air observation is equally important to combat, combat-support and combat-service-support units. Proper use of camouflage will help make up for an enemy’s superior knowledge of the jungle area.

Use small elements for trailblazing and rotate often. Trailblazing in the jungle presents different challenges than most reconnaissance units normally encounter, considering the OEs of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)/Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)/Operation New Dawn (OND). Regardless of the mission set of the reconnaissance unit and the surrounding terrain, making a new trail in the jungle is a slow and resource-intensive process. Planning considerations include the size of the trail that needs to be made, the size of the follow-on force, time available to establish a trail and available manpower.

As I said, blazing a trail is a very time-consuming process because only two to three individuals at most can be at the head of the formation shaping the trail. Unit leaders can choose to have the rest of the element slowly follow behind or to establish security halts to the rear of the trailhead and push trailblazers forward. The latter was the preferred method during the company FTX, as it allowed the platoons to establish hasty OPs to provide overwatch as the trail was slowly blazed forward. Leaders must be vigilant to ensure that security is constantly established while also making sure that trailblazers are rotated regularly to prevent exhaustion and maintain tempo.

When preparing men, weapons and equipment prior to trailblazing, Soldiers would make their jungle tools readily accessible (in addition to machetes, pruning shears are an effective and quiet alternative) and, once moving, attempt to make an opening wide enough to fit the appropriate-sized element through the terrain. In a dense rainforest environment such as Hawaii, a realistic planning consideration for trailblazing progress is 50 to 150 meters per hour.

Plan for and rehearse the use of ropes in maneuver. Jungle terrain and vegetation made maneuvering dismounted elements extremely difficult. Often, movement was limited to less than 200 meters in an hour. Drastic elevation changes forced formations into a file, forcing Soldiers to maneuver along ridgelines no more than three feet wide with severe drop-offs on both sides. Ridgelines also often took sharp dips, which drastically hindered our ability to move toward the objective safely. Widespread proficiency in how to deploy, use and recover ropes was essential to our scout elements while operating in a jungle environment. Platoon leadership always needed to be aware of where ropes were distributed throughout the formation, and rope set-up needed to be a well-rehearsed battle drill prior to LD.

Failure to conduct proper rehearsals and inefficient rope distribution in the formation led to an underuse of ropes and a subsequent loss in maneuverability, loss of stealth and increased casualties as Soldiers became injured from falling in the difficult terrain while carrying heavy loads. Ropes enabled both our ground scouts and follow-on forces to conserve time and manpower enroute to the objectives.

Strive to answer information requirements that support the follow-on attack. Constant terrain analysis is essential to successfully support the infiltration of follow-on forces. Our troop had an intimate knowledge of the infantry commander’s intent for movement and execution. Consequently, our scouts were able establish CPs along their movement route and identify key terrain for subsequent infantry maneuver.

Typical information requirements a follow-on infantry commander would need include suitable mortar firing points, support-by-fire locations, assault positions, OPs for command-and-control of the battlefield and, possibly the most important, the best tactical routes into and out of positions and locations. For these reasons, it is important for scouts and Cavalry leaders to be well-versed in offensive operations, be familiar with the combat power and capabilities of all units in the brigade, and have a good understanding of what terrain and approaches are most advantageous for infantry units in offensive operations. Once in close proximity to the objectives, we sent out small patrols to gather more information concerning possible avenues of approach for friendly assaulting forces on the objective, support-by-fire positions, water-resupply points, patrol-base locations and disposition of enemy early-warning forces around the objective. This was all information to enable the assaulting element.

After the more detailed area recon of the objective was complete, we established an OP along the approach route to provide early warning on enemy patrols heading toward the objective rally point (ORP) while other teams scouted the area for patrol-base locations and a water-resupply point.

Information gathered during the route reconnaissance enabled the battalion task force to make decisions concerning what avenues of approach could be used to maneuver toward the objective. The route-reconnaissance information also enabled the follow-on company to move quickly, quietly and with minimal risk due to pre-identified rope points, clearly marked trails and the presence of an OP providing overwatch on the route. The details gathered while conducting the closer-in area recon enabled the follow-on infantry platoon to conduct a much-needed water resupply; save time by moving to a pre-cleared patrol-base location; and execute stealthy maneuver at night to excellent support-by-fire and assault positions. Information gathered from long-range area reconnaissance gave the assaulting platoon an accurate picture of the enemy disposition and composition on the objective just before the assault. A combination of both the up-close stealthy and long-range recon enabled the follow-on infantry company to ultimately conduct a successfully coordinated deliberate attack on multiple complicated enemy objectives in difficult terrain.

Use stationary OPs to overwatch maneuvering scouts in low terrain. In addition to the challenges presented by terrain and vegetation during maneuver, effects on visibility due to terrain, vegetation and weather also required a change in tactics to accomplish the mission. Ridgelines and valleys provided the only options for maneuver. Unfortunately, valley floors contain the densest vegetation, impossible to pierce even with thermals, and ridgelines have many saddles that create dead space from the best OPs on the high ground. Low-lying clouds often reduce visibility at higher elevation from well over three kilometers to less than 100 meters.

To overcome these challenges, platoons performed a section-sized push-pull route reconnaissance down the descending route leading to the objective, with the rear section maintaining overwatch on the objective from the high ground about three kilometers away. The OP on the high ground could alert the section conducting the route reconnaissance to changes in the enemy macro situation on the objective and provide early warning in the event an enemy patrol left the objective toward the forward section’s position.

Using a combination of this push-pull method, traveling overwatch under cloud cover and updates on the enemy macro situation from the rear section’s OP on the high ground, we were able to conduct a thorough recon of our designated routes until each platoon was about 800 meters from their objectives. At this point, each platoon established an ORP and began preparation for a more thorough reconnaissance of the area around the objective in an effort to fill in what information our OP on the higher ground could not see. Platoons continued reconnaissance in this fashion until link-up with the follow-on infantry company.

Have a keen knowledge of your supported unit’s fires plan to be able to assist with observation. During execution, reconnaissance elements have the ability to free the maneuver unit from the obligation of observing rounds upon impact. Since the jungle is a densely vegetated environment with drastic elevation changes, maintaining visibility on an objective during movement can often be impossible. Therefore, scouts in already well-established OPs are invaluable in observing fires. Equipped with lasing optics, a scout can refine preplanned target locations to ensure first-round effects, thus more effectively preparing the objective before the assault. Without reconnaissance assets in the jungle, maneuver units may be forced to fire blind with an unrefined plan and hope to be able to adjust. It is key that the reconnaissance FSO knows the fires plan of the infantry force ahead of time – whether from the TF CAR or through radio coordination – to ensure continuity when scouts are required to observe the effects of preparatory fires before the attack.

Carefully consider water resupply and medical evacuation (medevac) when planning your routes. Our primary method of aerial resupply was a pre-packaged speedball that was cached along our route. Machetes again come into consideration to clear an area for Class I and Class V to be kicked out of a UH-60. The issue with aerial resupply comes again with the presence of a helicopter in sight of the enemy. We mitigated this by controlling the air corridor and separating the speedball dropsite with a piece of high terrain, masking it from the objective and thus out of eyesight from the enemy. Another method our task force considered was low-cost, low-altitude aerial resupply, but we were unable to do this due to weather conditions.

The key to incorporating water resupply in the jungle environment is to identify points along the route to resupply during map reconnaissance. With jungle operations being slow in nature, units need to plan water resupply in such a manner that routes do not need to be drastically altered and to prevent use of long-duration patrols to seek out water sources. If proper planning is not applied to address water resupply, leaders will find themselves altering their plans out of desperation and risking detection.

Due to the nature of the jungle and high precipitation in the OE, there were ample opportunities for resupply. We were fortunate to have been able to conduct water resupply at every water crossing we encountered using the Sawyer Mini Filtration System, but these opportunities may not always exist. Generally, we planned our routes to get to the high ground and remain there because this was the best opportunity for reconnaissance. However, these planning considerations needed to be balanced with the requirement to patrol to water sources. It was important to identify these potential sources during map reconnaissance because it allowed us to preplan our water-resupply points.

Also, a necessary consideration is the amount of water Soldiers are predicted to drink. The men were consuming four quarts a day, and we were able to hold 50 quarts per section. With this planning factor in mind, the troop was able to predict when each section would need water resupply throughout the week.

When conducting operations in the jungle environment, there is limited to no opportunity for ground evacuation of wounded or injured personnel. The primary method for evacuating Soldiers in the jungle is through hoist operations because after infiltration there are rarely opportunities to take advantage of open spaces for HLZs. During the company FTX, our route took us along a ridge, which provided limited opportunities for helicopters to extract Soldiers needing medical attention. For these reasons, always identify and look to incorporate high ground during your planning.

In one case, the use of machetes allowed us to cut down any trees and shrubbery to allow the medevac aircraft to set one skid down to receive our casualty because the hoist was disabled. Machetes can also clear trees and shrubs in the way of the hoist in thicker terrain. Keep in mind the second- and third-order effects on the mission during air-medevac. The presence of a helicopter will no doubt alert the enemy to the scouts’ location and potentially compromise the mission. Overall, since medevac can be dangerous for both the scouts on the ground and the pilots in the air, leaders need to exercise due diligence and prevent serious injuries by maintaining an appropriate pace and taking the necessary safety measures during movement.

Conclusion

“The only way to train for jungle operations is to train in actual jungle. … Unless troops live under conditions under which they have to fight, they will be dominated by their environment.” –LTG S.F. Rowell, commander, New Guinea Force, 19421

Jungle operations are slow, dangerous and exhausting. Mistakes in movement and planning can cost an attacking force time, manpower and equipment. Leaders need to make use of all time available after receiving the initial warning order to conduct necessary movement to prepare equipment and validate standard operating procedures with section-level rehearsals. Comprehensive platoon and troop rehearsals, together with tailored PCCs and PCIs, will set leaders up for success and buy commanders precious time. Once the LD is crossed, a detailed reconnaissance on both terrain and enemy is essential for a follow-on attacking force’s success. Once scouts have eyes on, the ability of leaders to think offensively will make reconnaissance more valuable to the infantry leaders we support.

From the arrival of the follow-on force at link-up through final forward-passage-of-lines, the Cavalry takes ownership of ensuring infantry leaders have a solid understanding not only of the enemy situation but also of the best terrain they can use to execute their attack. If executed in this way, our infantry brothers will see how well Cavalry can enable and shape their mission so the scales are tipped overwhelmingly in their favor when the time comes to initiate the attack.

Notes

1From LTC S.F. Rowell’s report on operations of the New Guinea Force, Aug. 7-Sept. 28, 1942, originally quoted in The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943-1944, edited by Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey (Canberra, Australia: Australian Department of Defence, 2004).

email

email print

print