From the Screen Line: The French Armor Contribution to Operation Serval (Mali)

line tactical armored personnel carrier and support vehicle that can be fitted with a selection of weapon systems, including a 12.7mm or 2mm Dragar turret, an anti-

tank missile-launcher turret or a variety of mortar systems. (U.S Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Robert M. Schalk)

Although the country of Mali has been struggling with a crisis since the military coup March 22, 2014, its troubles began well before this. In recent history, Mali has faced rebellions and uprisings involving the Tuareg people of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (NMLA); the terrorists of Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM); the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in Western Africa (MOJWA); and Ansar Dine.

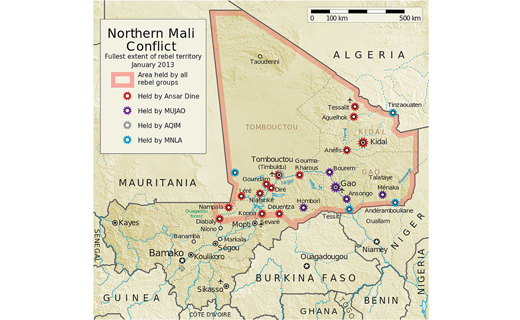

By Fall 2012, northern Mali was under the control of these rebels (Figure 1), and by early 2013, terrorist groups were reported heading south toward Bamako (the capital city). These security challenges led Mali to officially request military intervention from France.

On Jan. 11, 2014, in accordance with United Nations Resolution 2085, and five hours after France’s president gave the order to intervene, France launched a military operation named Serval. The main objectives were to stop the forward movement of armed terrorist and rebel groups toward Bamako, secure the Mali state and support the restoration of Mali sovereignty over its entire territory.

The first elements committed in Mali were armored forces of the French-led Operation Epervier, originating from Chad. They consisted of an Armor platoon of 1st Foreign Legion Cavalry Battalion equipped with ERC90 (a wheeled light armored tank mounted with a 90mm gun), attached to a mechanized, infantry-heavy combined-arms task force.1

The day after, a second combined-arms task force consisting of one troop of 1st Airborne Hussars Battalion, also equipped with ERC90, left the Ivory Coast and headed to Bamako in a 500-kilometer advance across Africa.

By late February, the total strength of the force had increased from 750 to 4,500 soldiers. Armor units were joined by four other combined-arms task forces: two reconnaissance-and-security troops2 and two standard Armor-heavy combined-arms task forces equipped with AMX10 RCR (a wheeled armored light tank mounted with a 105mm gun).

Operation Serval required an early-entry operation in a country twice the size of France. The first Serval commander, BG Bernard Barrera (commander of 3rd Mechanized Brigade), said that in leading “a large-scale offensive operation based on the operational tempo of the Armor,” key were maneuver down to platoon level, joint and combined-arms warfare, and integration of support (both fire support and engineer).

Adhering to the principle of centralization during decision-making and decentralization during execution, Barrera assessed that, alongside versatile equipment, a spirit of autonomy and the adaptability of leaders trained in combined-arms maneuver – together with the shock effect of Armor – led to victory.

The concept of maneuver for the first six months of the French operation in Mali was divided into three phases:

- Reconnaissance in force: In January, liberating the main occupied cities;

- Consolidate: From February to April, destroying AQIM and MOJWA;

- Stabilize: From April on, transferring authority to African forces.

Conducting multiple kinetic operations, opposed by an adaptive enemy (first withdrawing in contact and then deliberately defending its positions), Armor units led several offensive assaults covering more than 500 kilometers and lasting up to 48 hours (with only short pauses), as well as standard reconnaissance-and-security missions, including mobile-defense operations in the vicinity of airports of debarkation. A single armored combined-arms task force, detached from its original unit, conducted this latter mission, lasting more than eight weeks.

Contrary to their employment during operations in Afghanistan, Armor units used the full scope of their capabilities: protection, firepower, mobility, reversibility,3 fighting for intelligence and moving throughout wide areas. Moreover, Armor soldiers showed their excellent ability to bear extreme weather conditions – for example, warm temperatures (averaging more than 122 degrees Fahrenheit in turrets) or long-lasting standing positions during mounted operations and tactical bivouacs. As a whole, they won through adopting the Tuareg nomads’ skills to survive in their natural environment.

French Armor soldiers conducted operations where key factors were intelligence, mobility, unpredictability, massing forces to achieve local superiority and aggressive action to fulfill the commander’s intent. Armor units implemented doctrine while increasing the usual range of operations and allowing company commanders freedom to take the initiative – e.g., 30 of 50 operations conducted during the first mandate were combined-arms task-force-level operations, 15 were combined-arms battle-group-level4 operations and less than 10 were brigade-combat-team level.

Also, the task organization for every mission during the force-generation process in theater was based primarily on mission requirements. The leadership did not hesitate to modify the doctrinal structures of combined-arms task forces/battalions concerning operational needs. For each operation, armored combined-arms task-force commanders were attached with one infantry company (and detached of one Armor company) and were supported by engineers (one platoon), a forward air controller and intelligence assets (depending on the requirement, ranging from an electronic-warfare light group to intelligence-collection patrols, a working-dog team or a tactical unmanned-aerial-vehicle team).

To conclude, logistic support of the operation was a significant challenge. After the first two months of almost complete autonomy, battalion task forces termed the efforts of the support chain to ensure their resupply a “logistical miracle.” By March 2013, logistic forces had reached a strength of 1,200 soldiers, had driven more than one million kilometers and had provided 3,000 tons of freight. Although forces never lacked ammunition, gasoline, food or water, some gaps in maintenance and individual soldier support remained. The rate of operational readiness was nevertheless maintained at an acceptable level thanks to the predeployment initial stocks of the battalions, the continuous resupply by air and the constant involvement of crews and mechanics.

(Editor’s note: Operation Serval ended July 15, 2014, and was replaced by Operation Barkhane, launched Aug. 1, 2014, to fight Islamist fighters in the Sahel.)

Notes

1Combined-arms task forces are company-sized combined-arms units with an infantry company or an Armor/Cavalry company/troop as the core structure. They are thus infantry/Armor heavy and called Sous Groupement Tactique Interarmes, or SGTIA.

2Reconnaissance-and-security troops during Serval consisted of three anti-tank and reconnaissance platoons (equipped with wheeled light armored vehicles) and one direct-support platoon (equipped with a véhicule de l’avant blindé (VAB) wheeled armored personnel carrier).

3Reversibility refers to the ability to rapidly transition between offensive and defensive operations.

4Combined-arms battle groups are battalion-sized combined-arms units with an infantry battalion or an Armor/Cavalry battalion/squadron as the core structure. They are thus infantry/Armor heavy and called Groupement Tactique Interarmes, or GTIA.

email

email print

print