Saddles and Sabers: 70 Years On – Battle of St. Vith

is still strong in the region. (Photo by Bart Howard, 2013)

Lessons of leadership focusing on the armored side.

No matter how technology changes, the importance of leadership will never alter. Leadership will continue to be the intangible ingredient of success in conflict. Whether outnumbered or outgunned, the force that can exploit success, remain flexible, execute mission command and has the will to prevail – even under the harshest environmental conditions – may prevail.

In December 1944, in the small town of St. Vith, Belgium, American soldiers fought in one of the most savage engagements in the U.S. Army’s history. Their actions had implications far beyond their immediate foxholes and frozen tanks. Despite total tactical surprise, overwhelming odds and the coldest winter in generations, the young soldiers held off a determined enemy and denied the enemy any strategic success.

St. Vith is a story that is both commendable and tragic because combat is a human endeavor. Every leader has a unique “DNA” comprised of competence, training and resilience. In the same way, every unit has a breaking point, a threshold where defeat or victory can change in a matter of minutes. This is the story of American leadership in the Battle of St. Vith. As we observe the battle’s 70th anniversary, it is fitting to recognize that leadership remains relevant in modern combat operations.

Opening moves

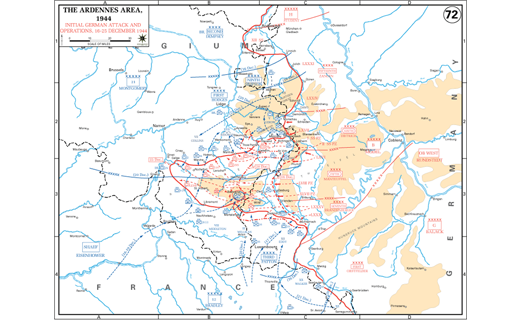

The evening of Dec. 16, 1944, was relatively quiet in the Ardennes sector. Although there had been scattered reports of a German materiel build-up to the east, the consensus of intelligence summaries discounted any large-scale attack. Much has been written about the intelligence failures of the opening days of the Battle of the Bulge; suffice to say, it may be a classic example of “mirror imaging,” whereas American conventional thought was to think what they would do if placed in a similar situation. A large scale of attack through restricted terrain – using precious reserves with inadequate fuel and an unrealistic timetable of advance – was not a course of action any American staff would entertain.

In 1944, the town of St. Vith was considered unremarkable except for the fact that five roads converged there. The Ardennes Forest region was covered in snow and slush, and all ground movement depended on the simplest logging trail or hardened path. Thus a plain country road took on disproportional worth. Three rail lines passed through St. Vith, turning this inconsequential town into a vital objective of the impending attack.

In the St. Joseph School on the southern edge of St. Vith, 50-year-old Washington native MG Alan W. Jones, commander of 106th Infantry Division, was uncomfortable with the circumstances in which he now found himself. His 106th “Golden Lions” were a classic “green” unit and an example of the downfalls of the highly industrialized U.S. Army mobilization and training system. The 106th had formed in 1942 and had participated in the Tennessee Maneuvers and all subsequent requisite training. That said, the heart of the division had changed a number of times as trained noncommissioned officers and officers were ripped out to form the nucleus of newly forming divisions. Like a vast factory line, this cycle occurred over and over.

After arriving in England Nov. 17, 1944, the 106th trained for a mere 19 days and then was rushed to France. Their introduction to the front was not unlike the reception of the many fresh replacements that were arriving to veteran units that winter of 1944. Arriving in open trucks in the dead of winter, cold and miserable, the 106th’s troops conducted a relief-in-place with the veteran 2nd “Indianhead” Infantry Division – “man for man and gun for gun.” The 2nd Division veterans had fought in the bloody Hurtgen Forest and had little sympathy for the 106th. They told the uneasy new soldiers, many only in their late teens, that they were coming to a “rest camp” and a “honeymoon sector.”

Nothing happened in the Ardennes. It was where new units were sent to learn the ropes, or veteran units to get a short rest.

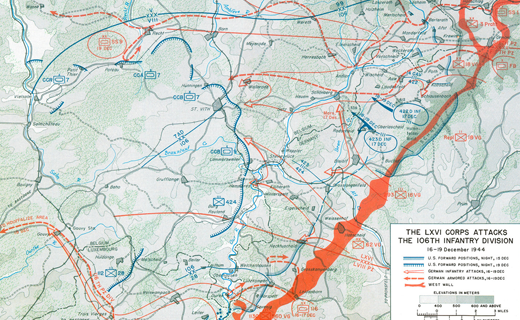

Despite this casual attitude, Jones believed he had inherited a bad hand. The entire tactical layout did not meet any training he had received during his 27-year Army career. Two of his infantry regiments, the 422th and the 423rd, were situated about 16 miles east of St. Vith along a terrain feature known as the Schnee Eifel (Snow Plateau). The steep hills, thick forests, lack of trails and swollen Our River hindered mutual support and made isolation a real possibility. His remaining regiment, the 424th, was due south of St. Vith.

If there was a bit of comfort for Jones, it was the presence of Combat Command B (CCB), 9th Armored Division, which was assigned in his area of operations. CCB consisted roughly of a modern brigade combat team of two armor battalions and one armored infantry battalion, augmented with supporting artillery and service-support units. CCB was led by the confident and combat-tested 50-year-old BG William M. Hoge. Hoge’s M4 Sherman tanks offered Jones the only mobile force poised to react to enemy actions, although they were forced to operate on roads since the ground remained a mixture of slush and mud.

Jones was also concerned about his northern flank, where there was a known vulnerability in the Losheim Gap. This seven-mile stretch of rolling hills was the scene of military invasions since the 1870s. The 14th Cavalry Group was assigned the mission of screening this critical area. Armed with armored cars, jeeps and some light tanks, the 14th could not doctrinally do much in this sector other than observe, report and call for artillery fire. Leading 14th Cavalry Group was 48-year-old COL Mark A. Devine, a controversial disciplinarian who once “inspected the fingernails of his men at the front line as an indicator of good order.”

On the evening of Dec. 15, most of 14th Cavalry was just trying to stay warm – and for a few brief moments, think of home. The most popular song that December was “I’m Making Believe” by the Ink Spots.

So Jones mulled over his options, and his staff noted his somber mood. The weight of command was upon his shoulders. He cared for his soldiers deeply. It was personal to him. His only son, LT Alan W. Jones Jr., was 21 years old and awaiting news of the birth of his first child back in Washington, DC. That evening, he was forward on the Schnee Eifel, serving as a junior staff officer in 423rd Regiment.

Commissioned in ROTC in 1917, Jones had served in the right assignments, attended Leavenworth and earned his right to command a division. As did many of his generation – GEN Dwight D. Eisenhower included – Jones had missed the “Great War” and, perhaps conscious of his lack of experience in combat, was reluctant to make any protests to his corps (VIII Corps) commander, LTG Troy H. Middleton. Reports of increased activity and the sounds of tank movement in the misty forests east of forward positions came into 106th’s headquarters, but VIII Corps discounted these reports as the indicators of a jumpy “green” unit.

‘We gamble everything’

A few kilometers to the east, the senior leader of the German 5th Panzer Army, 47-year-old LTG Hasso von Manteuffel, had meticulously prepared for the battle. A hands-on leader, he conducted his own reconnaissance and observation of American positions. Barely five feet tall, he was a dynamo of energy and was recognized as one of the most professional leaders in the German army. Not a fanatic, Manteuffel knew the odds were against his force, but perhaps with daring and his renowned drive, he could push past the thin American defenses and thus past St. Vith and Bastogne.

The 5th Panzer Army consisted of three corps of two armored and six volksgrenadier (VGD) or people’s divisions. On paper, 5th Panzer Army sounded impressive, but on closer examination, one would have seen ranks full of either the very young or old. Drained by the massive Soviet war machine, Germany had expanded its draft to take those who would not have qualified in 1939. Unlike the American army, the German army was not fully mechanized and still relied on a surprising number of draft horses to move supplies and even towed artillery. That said, with localized superiority of forces, an increase of ammunition stockpiles and a sprinkling of colossal 70-ton “Royal Tiger” tanks, the attacking force must have felt a surge of optimism as the first rounds of the opening barrage flashed into the cold winter sky. Audacity had carried Germany to victory in these very same woods in May 1940. The night before the battle, the German forces read an official communiqué which bluntly informed them that now they gambled everything.

Ghost Front awakes

Some soldiers reported seeing pinprick flashes of artillery fire in the sky before shells howled down on their positions, spreading shards of shrapnel, earth and tree fragments. Although the artillery strike caused some casualties, for the most part, the greatest effect was a disruption of communications throughout the 106th defensive line. Units relied heavily on wire communication, and the barrage had ripped apart miles of telephone lines. Radio communication had been severely limited for security purposes. When the fickle radio sets were finally turned on, many units discovered that German radio units had deliberately jammed the airwaves with musical records.

As soldiers jumped out of their billets and forward strongpoints prepared for action, ghostly figures in white camouflage emerged out of the thick woods in great number. The chatter of machineguns began to rattle all across the many villages and outposts. At this point, the battle could not be viewed as a coherent maneuver but as a patchwork of small, desperate battles at squad and platoon level. Some soldiers were killed outright; some panicked and fled in any available vehicle; many stood their ground and fought with determination. Small-unit leaders were the difference.

Jones must have felt enormous stress as his division command post attempted to gain a coherent picture of what was happening to the east. After all the exercises and maneuvers but with little more than 100 hours in a combat zone, 106th’s headquarters was completely blind.

To the north, 14th Cavalry was beginning to unravel. Possessing few anti-tank weapons, shocked at the size of the attack and without any orders, roads began to clog with vehicles desperately moving to the rear. When Devine entered his command post, he found it to be a “shambles.” Panic was contagious. The squadron commander of 32nd Cavalry had left his forward position in a “nervous” state to “find ammunition” in the rear and handed over command to his executive officer, MAJ John L. Kracke, who remained in command for the rest of the battle.

‘Lucky 7th’

More than 40 miles to the north in Heerlen, the Netherlands, newly promoted 43-year-old BG Bruce C. Clarke was preparing for a well-deserved leave to Paris. After five months of continuous combat, Clarke had proven himself to be one of the most dynamic and reliable Armor officers in the European Theater of Operations. As a combat commander in the famed 4th Armored Division, he performed magnificently in the breakout in Normandy and subsequently was sent to bolster 7th Armored Division as commander of its CCB. (Unlike the peacetime Army of the 1930s, commanders could be quickly replaced if deemed ineffective.)

Similarly, Clarke’s division commander, BG Robert W. Hasbrouck, had unexpectedly assumed command of 7th Armored in November 1944 by the personal direction of LTG Omar N. Bradley. The “Lucky 7th” had been in combat since August 1944. After fighting through France, Belgium and the Netherlands, the division had refitted and was poised to continue combat operations with U.S. Ninth Army. At 5:30 p.m. Dec. 16, 7th Armored Division was diverted to its own “rendezvous with destiny.”

Having determined that the attacks across the Ardennes front were more than a spoiling attack, Eisenhower directed Bradley to “send Middleton some help” in the form two armored divisions. The 7th Armored would move directly south from the Netherlands, and the 10th “Tiger” Division would move north out of the Saar River area toward a key town that would forever take its place in the annals of American military history: Bastogne.

With little prospect for rest, the 7th Division staff proceeded to draft a march order to place more than 11,000 men, 14 battalions comprised of 269 tanks, and hundreds of assorted trucks and wheeled vehicles on two primary routes through unknown territory in dreadful weather. The final objective was not clear. Real war was proving to be nothing like the classrooms of Fort Leavenworth, KS.

Clarke got on the road at once with a radio jeep and “an old Mercedes lent him by the division commander” and headed off into the night toward VIII Corps headquarters. It must have been a long, tense drive in the bitter cold as Clarke reflected on the myriad of details it would take to get CCB on the road and into battle. Most importantly, he had no picture of the enemy situation.

Clarke reached Bastogne at 4 a.m. The corps commander, the scholarly, bespectacled 55-year-old Middleton, was a highly experienced combat leader and was not easily rattled. He emerged from his sleeping van and explained to Clarke that 106th Division was “in trouble.” Two regiments (the 422nd and 423rd) were likely surrounded and out of communication. There were panicked reports of Tiger tanks everywhere. Clarke reflected later that there was an “air of impending disaster.” As Clarke listened, he must have been formulating a warning order in his head to relay to the division, which he hoped was already on the move.

Looking at Clarke and the still-black morning sky, Middleton had the experience to tell Clarke to get a bit of sleep and then head off to St. Vith at daylight. He knew this was likely the last respite Clarke would get for a long time. It was.

Failure of communication

Jones had received little good news since the attack of Dec. 16, but to his great relief, Middleton had informed him by telephone in an informal code that he was getting help in the form of a “big friend” with the name “workshop.” This was the code name for 7th Armored Division. An unknown staff officer at First Army had estimated 7th Armored’s arrival to be 7 a.m. Dec. 17. Middleton echoed this report to Jones. Although eased by this reinforcement, Jones still worried about his two eastern regiments. Without any word on their status and assuming they were under heavy attack, he wanted to collapse his lines and pull out 422nd and 423rd as soon as possible. The window for escape was closing. There were few viable roads that would allow the thousands of soldiers to cross the Our River and move closer to St. Vith.

With the telephone line crackling in and out, one of the most unfortunate miscommunications in the U.S. Army’s history occurred when, during a momentary break in the line, Jones believed that Middleton had directed that 422nd and 423rd remain in place and fight. The phone call ended, and Middleton informed his staff that he had “told Jones to pull his regiments off the Schnee Eifel.” Jones, still unsure of his instinct, accepted the predicament and laid hopes on 7th Armored’s imminent arrival.

VIII Corps’ assistant intelligence officer happened to be in St. Vith and overheard the conversation. He thought to himself that there was no possible way an armored division could move more than 50 miles on appalling country roads and arrive by morning. This was basic Fort Leavenworth Staff College work. How could he tell a division commander that the corps commander was dead wrong? He couldn’t and he didn’t.

After enduring heavy traffic and poor road conditions, Clarke reached 106th headquarters set in St. Joseph’s School at 10:30 a.m. It was abuzz with the activity of a staff fighting to gain a grip on the situation. Jones was immediately relieved to see Clarke, assuming that he had now arrived with an entire combat command. The erroneous assumptions about 7th Armored’s arrival time had built up false hope. Clarke now shattered any optimism. His combat power consisted of himself and his operations officer.

At that very moment, the two columns of the division were moving bumper to bumper, like two ponderous serpents, through appalling mud and slush. Curious at the new country they were entering, little did some soldiers realize that they were literarily at the crossroads of history near the non-descript town of Malmedy, Belgium.

Out of chips

Jones was certainly anguished at his difficult situation. He had unreliable communication with the 422nd and 423rd Regiments. Thousands of soldiers were fighting for their lives, isolated and cut off. To their north, 14th Cavalry Group was shattered and essentially ineffective. To the south, the 424th Regiment and CCB 9th Armored Division were fighting a sizable German force. This was no mere local counterattack.

The man of the hour was a 28-year-old former college football all-star, LTC Thomas Riggs. The epitome of charisma, Riggs was holding together a pickup team of elements of his own 81st and the attached 168th Combat Engineer Battalions, complemented by a collection of 106th Division headquarters personnel. Tasked with the mission to delay the enemy thrust along the narrow Schonberg-St. Vith road, Riggs and his men were demonstrating just how tough U.S. soldiers could be. As German tanks nosed forward along the narrow lane, they received a hail of small-arms fire, anti-tank rockets (“bazookas”) and a sprinkling of mortar and artillery fire. With the serendipitous arrival of a single P47 fighter-bomber, the lead panzer was knocked out and set ablaze, lighting the drab setting. The battle was no longer that of corps and divisions, but was now a “pickup” team of soldiers and a brave lieutenant colonel who understood that his mission was to defend a narrow Belgian road.

It was obvious to Jones that the battle was closing in on his headquarters. The unmistakable sound of small-arms fire and crack of tank cannons grew louder. Riggs and his men were barely holding on less than a mile away.

Suddenly Devine of 14th Cavalry burst into the schoolhouse in a state of shock. He pleaded for the headquarters to evacuate. Tiger tanks were apparently on the edge of town! Reading the situation, Clarke calmly recommended to Jones that it might be “best for Colonel Devine to personally report to Bastogne to render a report,” essentially giving Devine an excuse to leave the battle area. Clarke then returned to the situation at hand. Hours later, Devine narrowly escaped capture and death. Returning to his headquarters, he relinquished command to his executive officer and went to sleep. He was subsequently medically evacuated to the rear.

That afternoon, Jones turned to Clarke and blurted, “I’ve thrown in my last chips” – essentially delegating the fight to him. Clarke had little to fight with, since the 7th’s lead units were still working their way toward St. Vith, but he didn’t need Jones to tell him he was on his own.

‘Every dog for himself’

Unflustered, Clarke sent his operations officer, 27-year-old MAJ Owen E. “Woody” Woodruff, to look for CCB 7th Armored’s first vehicles and guide them in. Unknown to Clarke, the roads around St. Vith were jammed by a mixture of retreating and advancing American units. As elements of 14th Calvary and 106th fled eastward, fed by ever-increasing panic and rumor, 7th Armored Division was arriving from the north, and the competing convoys collided.

MAJ Donald P. Boyer Jr., the operations officer of 38th Armored Infantry Battalion, led CCB’s advance party. Wire-rimmed glasses and scholarly looks betrayed the fact that Boyer possessed the heart of a lion. As his jeep approached the crossroads of a few scattered buildings known as Poteau, he surveyed a scene that shocked him deeply. What he saw was a mixture of American vehicles in every state of panic, some driven by lone drivers, all moving west, with the only goal of getting away from the Germans. As Boyer later remarked, “It wasn’t military; it wasn’t a pretty sight … It was every dog for himself.” Boyer immediately took charge, and for the next few hours, he tried to restore order to clear a path for 7th Armored Division reinforcements.

A few miles to the south, having grown restless, Clarke ventured from his new headquarters and found Woodruff in the same predicament as Boyer – attempting, albeit unsuccessfully, to reinstate order. An unknown battalion commander had threatened to “shoot” Woodruff. Clarke found the offending officer, placed him at attention and reversed the threat of execution. At that point, Clarke became the highest-ranking “traffic cop” in the U.S. Army.

Ironically, Manteuffel was doing the exact same thing only a few kilometers to the east. The attacking forces had become frustratingly tangled on the narrow logging trails.

Into the fray

By dusk Dec. 17, CCB was finally entering the fight. Clarke directed his small headquarters to co-locate with 106th Division. The 7th Armored exuded confidence, while 106th was mentally beat. Staff officers in the 7th noted that their counterparts were “packing up their gear” as if the whole affair was over.

While some men had lost the desire to fight, others displayed remarkable tenacity. One such officer was LTC Roy Clay, 33, the diminutive yet pugnacious commander of 275th Field Artillery, a VIII Corps unit that was assembled near Ober Emmels. Clay had been assigned to Devine’s 14th Cavalry and had grown frustrated in Devine’s inability to employ Clay’s unit. Once the 14th essentially collapsed, Clay refused to pull out and went looking for a mission. Finding Clarke, Clay gave a simple request: “I want to shoot.” Here was a fighter in Clarke’s mold. Clarke had no hesitation and exclaimed “God bless you, Clay, you’re the only artillery support we have. Head out and shoot in support of those engineers on the ridge east of town.”

For the rest of the battle, the 275th Artillery provided non-stop fire support. The 7th Division’s battle log records unabashed praise of these valiant gunners, who provided a dose of valor.

The first unit to exit the road and enter the fight east of St. Vith was 87th Reconnaissance Squadron, commanded by 31-year-old Vincent “Moe” Boylan. A graduate of West Point, Boylan was a native of Brooklyn who had two interests as a boy: soldiering and horses. Like a trooper from a Western movie, he arrived just in time to get his lightly armed mechanized troopers into the firing line. Although not designed to fight in close quarters, 87th Cavalry adapted to the defensive mission and, at one point, was credited with destroying a mighty Royal Tiger at a range of a few yards with a 37mm gun by a near-suicidal crew of a tiny M8 armored car.

The 38th Armored Infantry Battalion, commanded by 36-year-old LTC H.G. Fuller, followed next and began to form a horseshoe-like defensive cap to the exit of the Schoenberg road. Fuller was a proven commander, having earned the Silver Star for heroism in Holland a few weeks before.

Next, a company from 23rd Armored Infantry and a Sherman tank company of 31st Tank Battalion joined the battle line. The tankers of the 31st were ready to fight. At 30 years old, with a wife and daughter back in Mansfield, Ohio, LT John J. Dunn of Company A, 31st Tank Battalion, was older than his peers were and, one might have suspected, more cautious. However, about a kilometer from St. Vith, Dunn spotted three German tanks and at least 100 enemy infantrymen. Temporarily shielded by a turn in the road, he quickly issued an order by radio and then led his platoon of five Sherman tanks forward, engaging the enemy at point-blank range. All three panzers were destroyed, as was most of the enemy infantry. Securing the high ground along the Schoenberg road, this tiny force remained throughout the night and defended against repeated counterattacks as 7th Division’s remaining units took their place in the St. Vith sector.

Clarke’s CCB, alongside Hoge’s CCB 9th Armored Division, formed a larger arc around the town of St. Vith. Combat Command R (Reserve) under the command of COL John L. Ryan deployed into a defensive position north of St. Vith and oriented on a crossroads village named Poteau. In classic Armor fashion, a counterattack force made up of Combat Command A under COL Dwight D. Rosebaum remained a few miles to the rear, ready to blunt an enemy breakthrough or to exploit an exposed weakness. The infusion of tanks, fresh infantry units and raw determination was changing the balance of the battlefield, yet a major tragedy was still underway just a few miles to the east. The fate of the 422nd and 423rd Regiments had yet to be revealed.

In his new headquarters in Vielsalm, Jones now confirmed that due to poor weather and poor coordination, the anticipated aerial resupply of his trapped regiments would never occur. The fate of his son in the 423rd must have weighed heavily on his mind.

By the evening of Dec. 19, 7th Armored Division was fighting three German divisions. The 1st SS Panzer was hacking away at Poteau, now defended by CCA, which had been committed the day before to reinforce CCR. Clarke and CCB held on to the St. Vith area against the 18th and 62nd VGD divisions. Having met stiff resistance in the north, the Germans now probed south of St. Vith, but Hoge’s CCB 9th Armored held solid.

A pattern was developing. The Germans were desperately looking for a point of weakness along American lines. For hours on end, hundreds of German infantry, supported by tanks and artillery, would assault the American lines. The Americans would parry, taking losses but pushing the Germans back. After a pause, the attack would resume at a different point. As every hour passed by, the Americans were gaining time, for the German strategy depended on rapid advance and capture of fuel and supplies.

As an indicator of the confusion of such a battle, the 112th Regiment of the 28th Division – whom the Germans called the “Bloody Bucket” Division for their patch – commanded by COL Gustin M. Nelson, was “discovered” just south of Hoge’s CCB. Cut off from its parent division, 112th had continued to fight on and was now attached to 106th to support the struggle centered on St. Vith.

It is worth noting that throughout this period there was little effort to formalize command and control. The senior commander in the area was clearly Jones, yet 7th Armored Division under Hasbrouck was VIII Corps’ main effort. Hoge cooperated with Clarke without being formally “attached” or “in support.” Such command arrangements would have received an academic failure at Fort Leavenworth, but the leaders’ personalities made it work and focused on the mission at hand.

Flexibility was the watchword for 7th Armored Division. Without modern command-and-control technology or use of the term “modularity,” 7th Armored was comfortable with the creation and dissolution of task forces and employment of a mobile defense. For example, on Dec. 20, a significant German threat developed to the south, near the railhead village of Gouvy. To counter this, 7th Armored directed a mixed collection of tank destroyers, tanks, infantry, engineers and artillery to be placed under the control of former Georgia attorney LTC Robert B. Jones, commander of 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Throughout the rest of the battle, Task Force Jones would provide yeomen’s work, closing gaps and defending the flank of St. Vith. In the same way, independent units of cavalry and light tanks screened gaps in the defense far away from their parent units, with little guidance or oversight.

Enter Monty

A soldier in battle is only concerned with his immediate surroundings – yards that mean life or death – and has little knowledge or interest in the doings of the generals, also known as the “brass.” As the battle raged on in the slush and mud of Belgium, Eisenhower grappled with significant challenges in command.

The Battle of the Bulge, as it would later be named, was two distinct fights: the now legendary struggle around the town of Bastogne and the fight for the crossroads of St. Vith. Bradley was in charge of both, yet communication between north and south was impossible. The solution was controversial, logical and arguably uncharacteristically “bold” for Eisenhower. Looking at the map and seeing the amount of forces now committed to the battle, he split the area in half and announced that Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery would be placed in command in the north. Within hours, a spirited Monty – whose tremendous professionalism and strategic skills were clouded to Americans by his irascible personality and unabashed British manner – was on his way to First Army headquarters in Chaudfontaine, Belgium, to “tidy things up” and get a “grip” on the situation. Little did the men of 7th Armored Division know that this change would have a significant impact on their fate.

MG Matthew Bunker Ridgway, 49, was already a legend in the U.S. Army. One of the original paratroop generals, Ridgway was a “lead from the front” officer now in command of XVIII Airborne Corps. Ridgway had just been named the senior tactical commander of the St. Vith sector. As 106th Infantry and 7th Armored Divisions fought near St. Vith to the east, a defensive position consisting of the newly arrived 82nd Airborne and 3rd Armored Divisions under XVIII Corps command was forming along the Salm River to the west. Although very different in style, Montgomery and Ridgway were both arriving to restore order to this desperate fight.

Breaking point

Every man and every unit has a breaking point, and 7th Armored was rapidly reaching its own. The defense east of St. Vith had been anchored on the infantry defense under the command of Fuller’s 38th Infantry. U.S. forces had suffered nearly 80 percent casualties. Everyone felt the agony of frostbite and suffered lack of sleep, hunger and dehydration. The cold, which was an enemy all its own, sapped the strength and courage of all but the strongest. The dead and wounded could not be evacuated.

Fuller returned to Clarke’s headquarters to relay the situation and then suffered a mental breakdown. He could not go on. His executive officer, Boyer, doggedly continued to fight with what he had until he was ordered to withdraw. Boyer was subsequently captured, painfully reminiscing in an interview 20 years later that for him “the world had come to an end.”

Once given the order to withdraw, some men were unwilling to disengage. In one instance, a trooper from 87th Cavalry Squadron, SGT Leonard Ladd, travelled to Clarke’s headquarters to personally get the order to retire westward. Ladd patiently waited and then announced to the general: “Me and my men didn’t like the idea of leaving the front, so now I just wanted to get it straight that we were ordered out by you.”

Weary, cold and dirty, these were quintessential soldiers. It was these types of men who were holding back the bulk of the German army. Tenacity and effective small-unit leadership were the glue holding the American line.

‘Back with all honor’

Ridgway was never one to stand still and soon was at the combined 106th/7th Division headquarters at Vielsalm, interrogating Jones and Hasbrouck. As a paratrooper, Ridgway discounted a mobile defense as an option. For him, the obvious course of action was for 7th Armored to remain in a “fortified goose egg” and hold out. Resupply would come from “airdrops.”

Hasbrouck must have shown obvious frustration. He later reflected: “To an infantryman, a tank was a place of refuge. But to a tanker, a dug-in tank was only a metal death trap containing a ton of high explosives and many gallons of gasoline. It was nonsense, making a useless stand on that terrain. The fight should be on ground of their own choosing under the most favorable conditions of armor.”

Giving up ground was abhorrent to Ridgway. He knew that 101st Airborne Division was valiantly holding on in Bastogne. To men like Clarke, the ground around St. Vith “wasn’t worth a nickel.” All that mattered was delaying the Germans, hour by hour, day by day, until the corps and Army could form a larger counterattack. If that meant dropping back and fighting from successive lines, so be it.

To Ridgway’s credit, he decided to assess the situation for himself and talk to his commanders. Along with Hasbrouck, he moved forward to Clarke’s headquarters. Clarke was a straight shooter and gave an accurate picture. The command was worn down and holding by a thread. Ridgway, unconvinced, arranged a meeting with his old friend Hoge a few kilometers away. They had been on the same 1917 West Point football squad. Hoge would be the gauge.

When told that Ridgway was contemplating a total withdrawal, Hoge didn’t blink and only asked “how”? With that, Ridgway had his answer and put all his energy into a plan to pull the division back behind the Salm River.

Montgomery had also made up his mind. With the input of his many liaison officers spread throughout the battlefield, Monty concluded that the 7th had accomplished its mission and directed the division to “come back with all honor.” Years later, Montgomery would still be a point of controversy for senior American officers, but not to the officers and men of the Lucky 7th. They credited Montgomery with making a correct read of the battle and saving the division from encirclement.

Ridgway then returned to Vielsalm for one more piece of business. Having made an estimate of the men he was working with, the time had come to make a change. He informed Jones that he was now one of his deputy commanders, essentially relieving him of command. Late that evening, overcome with the situation, Jones collapsed, suffering a massive heart attack, and was evacuated to a hospital, never to command again. For him, the loss of his division, the unknown whereabouts of his son and the profound stress of the battle had brought his world to a tragic end.

A lucky ‘Russian High’

On Saturday, Dec. 23, 7th Armored Division awoke to a unique weather phenomenon known as a “Russian High.” This freeze dropped temperatures and allowed for increased mobility of wheeled and tracked vehicles. Up into that time, the ground had been such a quagmire that possibility of entrapment was real. Now it was as hard as a rock.

Under pressure from attacking German forces, the jumble of units began the complex movement of withdrawing westward. The plan didn’t go according to any Leavenworth design. Although chaotic, there was no panic. Clarke found himself again directing traffic. He was on the point of collapse; only the adrenaline of one more push was keeping him upright. Units intermingled; 112th Regiment was almost left behind in the confusion of orders. Rear guards fought off scattered panzers, which nipped like wolves on the hunt. Unknown to the Americans, the enemy was suffering horrific logistical and traffic problems and could not fully transition to a pursuit.

Soon the sun had set, and the situation grew ever more complicated as enemy and friendly units intertwined in the eerie moonlight of a full moon. The last unit out was appropriately the first unit in: 87th Cavalry under Boylan’s command. Hasbrouck sent a message for Boylan to meet him near the passage lane. Expecting a classic butt-chewing, Boylan received an embrace. Hasbrouck, normally stoic, blurted out, “Thank God, Boylan, you’re here, you got everyone out!”

Not far away, his unit now out of the line, Clarke collapsed in a jeep and slept for the first time in days.

Many miles away, LT Alan Jones Jr. and thousands of other brave men were just beginning their own journey through hell. Perhaps they felt like failures, yet the delay at St. Vith had thrown the German timeline in such disarray that victory was now impossible.

Aftermath

Within days, the powerful forces of the Allies converged on the epic “bulge” to slowly push the enemy eastward back to the border of Germany – and eventually beyond. The battlefield was strewn with the human and material debris of war. Hitler’s immense gamble was a failure. Initially shocked and stunned, American forces regained their composure and fought with determination. Delaying the advance in the north through St. Vith and denying the crossroads of Bastogne had doomed any thought that the Germans could split the Allies and achieve anything more than a local victory. The Allied partnership held firm, and losses in men and material were quickly replaced. Nothing could shake the determination to demand Germany’s unconditional surrender.

In the St. Vith sector alone, at least 4,000 Germans were killed or wounded. Perhaps the lucky were those who were captured. Taken by the Allies, they knew the war was over for them, unlike their comrades who fought the Soviets. Their fate was only death.

Although Bastogne is remembered as “the” battle of the winter of 1944, the actions of 106th Infantry, 7th Armored and all attached units deserve an honored place. The reasons St. Vith was overshadowed reveal the complexity of human nature and memory. Bastogne was never taken. The story of the acting commander of 101st Airborne Division’s “Screaming Eagles” reply to the German demand to surrender with the single word “Nuts” appealed to a sense of drama. Bastogne made good press.

On the other hand, the enemy eventually captured St. Vith, yet the Allied mission was accomplished. It is hard to explain a battle of delay as a victory. Furthermore, the U.S. Army was uncomfortable with 106th Division’s destruction. As the years passed, the bitterness of its veterans grew. Told they were in the “honeymoon sector” and their concerns and reports were those of a green unit, they suffered the humiliation of mass surrender. They exposed the U.S. Army training system’s deficiencies. Continually bled to create cadres for other units, 106th Division was never able to reach a peak of cohesion and proficiency. Coupled with the dismal failure of 14th Cavalry’s senior leadership, the defeat of 106th Division was not one the Army wanted to dwell on.

In contrast, 7th Armored Division displayed the qualities of decisive action and flexibility at all levels. Leaders like Clarke and Hoge would prove to be the best of a generation and would rise to the rank of general. Small-unit leaders showed themselves to be competent and effective. Reconstituted within a few days of St. Vith, 7th Armored fought on victoriously into Germany and added to their box score of victories.

Legacy

On a warm summer day in July 1948, veterans of CCB 7th Armored Division formed up at Fort Knox, KY, for the presentation of the Presidential Unit Citation. The assembled group stood at attention and a narrator read off the citation, concluding: “By their epic stand, without prepared defenses and despite heavy casualties, [CCB 7th Armored Division] inflicted crippling losses and imposed great delay upon the enemy by a masterful and grimly determined defense in keeping with the highest traditions of the Army of the United States.”

It was a day these Soldiers would never forget. Now 70 years on, we may honor them by remembering what happened in an obscure Belgian town named St. Vith where small-unit leadership proved, as it always will, to be the vital component to success in conflict.

(Author’s note on sources: There are multitudes of excellent books on the Ardennes Campaign. Hugh M. Coles’ 1965 Battle of the Bulge of the Army’s Green Book Historical Series is invaluable. Charles B. MacDonald’s Time for Trumpets (published 1984) is superbly detailed. John Toland’s Battle: The Story of the Bulge and John S.D. Eisenhower’s The Bitter Woods contain many first-hand accounts. Ernest Dupuy’s St Vith: A Lion in the Way remains the best description of the 106th Division’s fate. Copies of 7th Armored Division’s original battle logs are available with a bit of search on the Internet. Finally, a unique resource is the 1965 “Big Picture” documentaries St Vith Parts I and II found on YouTube. Many of the characters in this article give their personal reflections of the battle there.)

Also available: The Armor School’s publication, The Battle at St. Vith, Belgium Dec. 17-23, 1944.

email

email print

print