Saddles and Sabers: Decisive Leadership – BG Bruce C. Clarke and the Battle of St. Vith

U.S. M4 Sherman tank, right, to the German ‘Royal Tiger,’ left), delayed the

Germans long enough to disrupt the Wehrmacht’s timetable for reaching Antwerp, Belgium, in the German Ardennes counteroffensive of December 1944.

Reprinted from ARMOR, November-December 1993 edition

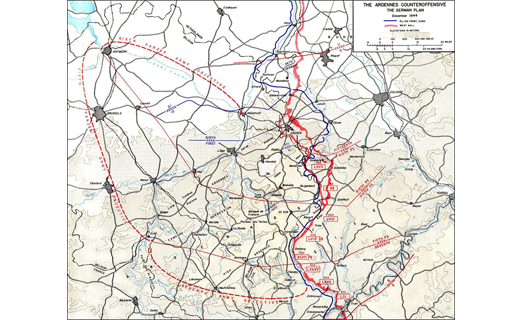

"Hold the reins loose, and let the armies race."1 All along the 80-mile front during the early-morning hours of Dec. 16, 1944, the screams of the German Nebelwerfer rockets and the crash of heavy German artillery exploded the quiet. Twenty German divisions, with almost 800 tanks, attacked west. The Wehrmacht was on the march again, and this time, they claimed, they would go all the way to Antwerp and capture the city as a Christmas present for their Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler. The fate of the Fatherland was at stake, and the Wehrmacht, as in 1940, again seemed unstoppable. GEN Walter Model's words on the eve of the assault were: "The first objective is to achieve liberty of movement for the mobile forces."2 For the Germans, it was now or never.

Dec. 16 was a black day for the U.S. Army. Rumor dominated the battlefield. The enemy's unsuspected attack had unsettled the defending Americans. No one seemed to understand what was happening. Overwhelmed by the surprise and fury of the assault, Americans began to surrender and run. The 106th Division, nicknamed the "Golden Lions" – a green division fresh from the United States – was shattered by the fury and skill of the attacking Wehrmacht. More than 7,000 soldiers from the 106th Division surrendered. Some small, isolated units held and fought bravely, but it was not enough. The front was disintegrating. Disaster was in the air. The scene was one of wild confusion and disorganization. The Allied high command, unable to develop an accurate picture of the situation, reacted slowly to the Wehrmacht's massive blow.

LTG Troy H. Middleton, VIII Corps commander, was responsible for a large portion of the Ardennes area. His information was sketchy. Rumors of German panzers overrunning everything in their path were rampant. Recognizing the value of St. Vith, a vital road and rail center in the northern portion of the Ardennes, Middleton asked for reinforcements. He obtained the release of 7th Armored Division from Army reserve and immediately deployed it to St. Vith.

The 7th Armored Division received its orders to move to St. Vith late the evening of Dec. 16. The 7th was located to the north, near Heerlen, the Netherlands, and was undergoing a "major shakeup in the command structure."3 The 7th was a "hard luck" division. Its record of accomplishment on the battlefield was poor. The previous division commander had been relieved for incompetence. Its new commander, MG Robert W. Hasbrouck, had only been in command since Nov. 1, 1944. But the 7th would have to do. There was no one else.

The commander of 7th Armored Division's Combat Command B (CCB) was BG Bruce C. Clarke. He had enlisted as a youth in the New York National Guard and then received an appointment to West Point. Initially assigned as an engineer, he had volunteered for service with tank-mechanized units as soon as the Army began forming them. After 20 years in the Army, he had earned a reputation as an excellent leader and a determined fighter. He took command of CCB and was promoted to brigadier general only 45 days before the German attack in the Ardennes.

Clarke arrived in St. Vith Dec. 17, 1944, ahead of his command and with only his operations officer (MAJ Owen E. "Woody" Woodruff) and two drivers.4 The scene in St. Vith was pandemonium. Clarke immediately reported to MG Alan W. Jones, commander of what was left of 106th Division. Jones had a defeated attitude. He talked only of retreat and disaster. He doubted that anyone could stop the Germans. His last words to Clarke before relinquishing command of the area of operations were, "You take command. I've got nothing left. I've thrown in my last chips."5 The sole responsibility for victory or defeat was now Clarke's.

With little more than a month in command, and with his command strung out along 96 kilometers of congested, ice-caked roads, Clarke was about to fight one of the most difficult battles in the history of American arms. He was outnumbered by the Germans more than eight to one. How was Clarke going to succeed against such odds? Why should his unit fight effectively while the rest of the American forces in the battle area were in headlong retreat?

Before the battle

Clarke took over CCB of the "unlucky" 7th Armored Division Nov. 1, 1944. But Clarke was not new to combat. He was a veteran commander of Combat Command A (CCA), 4th Armored Division. His old unit had distinguished itself in combat since the early days of the Normandy landings, five months before the Battle of the Bulge. He had done a terrific job commanding CCA during LTG George S. Patton's breakout from the Normandy beachheads. He had seen almost continuous combat since D-Day (June 6, 1944) and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star with two oak-leaf clusters, Bronze Star with oak-leaf cluster and Air Medal.6

Immediately after taking command of CCB, 7th Armored Division, Clarke worked and trained his command hard. His style of command was positive, proficient and no-nonsense. The men of CCB were impressed with their big, barrel-chested, 6-foot-tall commander. Clarke later related, "It took a lot of training and coaching to turn this division around to play the key, successful role in stopping [General der Panzertruppe Hasso von] Manteuffel six weeks later at St. Vith."7

In 4th Armored Division, Clarke had employed the techniques of command that were to be so successful in the St. Vith area. As a veteran of 4th Armored Division, Clarke had learned the hard lessons of armored combat. His command style incorporated three essential pre-battle decisions: organizing his forces into self-contained forces capable of independent action to the maximum degree possible; streamlining the information flow to the maximum extent possible; and his strong belief in forward command.

Clarke recognized the value of self-contained forces. He reorganized his command for built-in flexibility. He recognized the fact that mobile, armored formations required a quick decision cycle to take advantage of enemy mistakes and the fleeting opportunities of the battlefield. His intent was to make his armored combat command "seem like an armored corps."8 He made sure that the subunits of this combat command, the battalions, had the necessary combat-support and combat-service-support elements to fight independently if necessary. This organizational decision gave Clarke’s subordinate commanders the ability to act without active control from above. They had the organizational capability, and were given the operational flexibility, to achieve objectives within their scope of operations without constant supervision.

Secondly, Clarke streamlined the flow of information up and down the chain of command. He employed mission-type orders. He believed that "mission-type orders were a requirement if the most was to be obtained from a command."9 His combat-orders technique involved eyeball-to-eyeball verbal orders issued from a vantage point overlooking the battlefield. His subordinate commanders were expected, and trusted, to make decisions within the guidelines established by his intent.

Clarke's intent was for his subordinate commanders to command their units and not wait around for instructions. When decisions are made at the point of execution, it is possible to take advantage of battle opportunities as they occur without losing time. "Time is always critical and mission-type orders save time. The command style and staff functioning that contribute most to maneuver warfare is characterized by the application of 'mission orders.'"10

Clarke's orders were usually oral, quick and to the point. He told his commanders what to do, not how to do it. Clarke’s technique of employing mission-type orders was not new to the U.S. Army but was particularly important in creating the short decision cycles demanded of fast-paced maneuver warfare.

Clarke explained how to give mission-type orders in his book, Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander. He said that to get maximum combat power, we must have plans flexible enough to meet rapidly changing situations. But careful planning is not enough; this must be coupled with the readiness to change and adapt to situations as they are, not as they were expected to be.

Basically, a mission-type order needs to cover only three important things:

- It should clearly state what the commander issuing the order wants to have accomplished;

- It should point out the limiting or control factors that must be observed for coordinating purposes; and

- It should delineate the resources made available to the subordinate commander and the support which he can expect or count on from sources outside his command.11

Lastly, Clarke was a true believer in the concept of forward command. Forward command is an essential element for achieving tactical victory in maneuver warfare. Forward command calls for senior commanders to issue orders based on personal observation and to actually assume command of a subordinate unit during a critical point in the fighting. This concept relies heavily on thinking, independent leaders; unflinching trust in subordinate officers to carry out the mission within the intent of the senior commander; and the clear understanding of the missions of the units two echelons down and two echelons up.

Clarke did not believe in a "systems" approach to war, a prescribed logical process leading to a quantified decision. He believed that "[t]he commander should be forward as much as possible to detect early the critical situations in all fields and to render help quickly to his units when it is needed."12

At St. Vith, he seemed to appear everywhere there was a crisis. He frequently visited the front lines to get the true "feel" of the situation. Several times, he personally directed traffic. At the village of Commanster, for example, when nine artillery battalions tried to displace at the same time, Clarke was there, unsnarling the mess, and getting vital combat power moving in the right direction.13

During the battle

Jones turned over the defense of St. Vith to Clarke at about 2:30 p.m. Dec. 17. Clarke was hardly in an enviable position. He could hear the crash of artillery and the sound of machinegun and small-arms fire. The roads leading to St. Vith were clogged with Belgian refugees and retreating American soldiers. Every kind of vehicle seemed to be heading west, away from the Germans. As MAJ Donald P. Boyer Jr. said, "It was a case of every dog for himself; it was a retreat, a rout."14 Movement toward the front was reduced to one mile an hour in many locations. Only a few units were standing to hold back the Wehrmacht, and his own forces were strung out along a 96-kilometer route of march. Clarke’s first combat experience as a brigadier general seemed less than promising!

But Clarke did not give up. He took charge and organized everyone he could scrape up to defend the positions around St. Vith. "By midnight of Dec. 17, a fairly cohesive defense had been established in front of St. Vith with three companies of armored infantry, a company of medium tanks and a troop of cavalry," commented historian Charles B. MacDonald.15 Clarke adapted and improvised the defense of St. Vith as fast as his CCB units arrived. At 2 a.m. Dec. 18, 1944, the Germans launched the first of many attacks against the St. Vith positions. "Throughout all this mayhem, only one thing was certain, [Clarke] was the sole defending commander of St. Vith," wrote CPT Stephen D. Borows.16

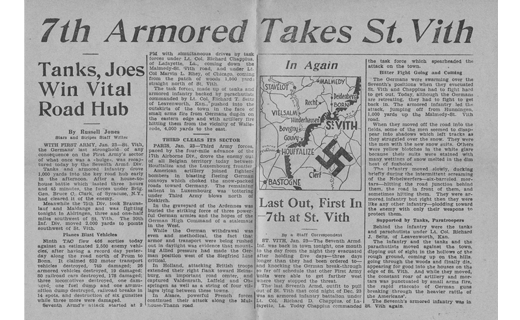

Clarke did more than just defend. He aggressively employed small-unit counterattacks and blunted one German attack after another. According to Charles Whiting, "Clarke's 7th Armored men showed that men in combat, confronted with a sudden and confused situation, could act aggressively, immediately and independently."17 Clarke continued his mobile defense of St. Vith with determination and skill, giving ground but killing and delaying the Germans in the process.

Clarke displayed decisive leadership during the Battle of St. Vith. His missiontype orders streamlined his command-and-control system and aided his efforts to employ his mobile reserves with decisive speed. His forward command during the battle ensured the timing of these vital counterattacks. His style of command allowed his subordinate commanders to act without active control. When communications were lost, they fought on, implicitly understanding what their commander expected, and continued the fight. In this fashion, Clarke's presence was felt everywhere throughout the battle.

Between Dec. 17-23, 1944, Clarke's command fought off continuous German attacks. His aggressive tactics confused the Germans and made them believe they were up against a much stronger force than merely one reinforced combat command. Clarke orchestrated massed artillery attacks on the advancing Germans, followed by extremely agile, mobile counterattacks. His counterattacks were often composed of as little as company-sized units of tanks, which swept through the advancing enemy and returned to be used for further action. When MG Matthew B. Ridgway questioned Clarke about giving up ground, Clarke replied: "General, I don't think you know what they are trying to do. This terrain is not worth a nickel an acre to me. In my tactics, I am giving up about a kilometer a day under enormous pressure, but my force is intact, and I am in control of it. A few kilometers' advance cannot be of any substantial value to my German opponent... He must, I believe, advance many kilometers to accomplish his mission. The 7th Armored Division is preventing him from doing that. We are winning, he is losing."18

On Dec. 23, Clarke was ordered to disengage and withdraw from St. Vith. His men were fatigued from five days of continuous fighting. His ammunition, especially his artillery ammunition, was dangerously low. Issuing verbal orders to his command, Clarke disengaged his forces one at a time. H-Hour was set for 6 a.m. No men or operational vehicles were left behind. By 11 p.m., he had successfully disengaged his entire command and was regrouping well behind American lines in an assembly area in the vicinity of Xhoris, Belgium.

His disengagement was successfully executed. "Covering forces to the east, west and south fought bitter rearguard actions as the enemy pressed hard on the retreating division's heels," Borows wrote.19 Defiant, his CCB had disrupted the German timetable and marched away, bloodied but intact. He had led his command in the most critical test of American arms in World War II.

CCB, under Clarke's command, was the mainstay of the defense of St. Vith. Because of his gallant stand in and around St. Vith, the Allies were able to regroup and hold at Bastogne. LTG Troy H. Middleton recognized this and later said, "In my opinion, it was CCB that influenced the subsequent action and caused the enemy so much delay and so many casualties in and near this important area."20

Conclusion

"It was no small achievement in military history that a reinforced combat command of 10,000 American soldiers had warded off [more than] 87,000 enemy troops and had prevented them from controlling St. Vith for six days," said Borows.21 The defense of St. Vith was the turning point in the Battle of the Bulge. Before St. Vith, the Germans had everything their way. After St. Vith, the failure of the Wehrmacht's attempt to win a quick, decisive victory in the West was apparent to both sides. The 7th Armored Division held the German onslaught for six critical days. Those six days made the difference between victory and defeat.

Decisive leadership is often the key to victory. In this example, the leadership of one man had a decisive impact on the outcome of a battle and, perhaps, the outcome of World War II. Clarke's successful leadership depended on his actions before the battle. His organizational and information decisions before the battle, combined with an effective orders-process technique, prepared his command for its decisive role at St. Vith. He molded CCB into a flexible, self-contained fighting unit, capable of executing mission-type orders, in little more than a month.

Clarke trained his unit to conduct mobile operations before the battle. He had coached and developed his junior leaders to effectively employ the elements of combat power. Due to these organizational and informational decisions before the battle, his unit was prepared to conduct mobile, armored operations against the massed might of the Wehrmacht.

Clarke's actions at the Battle of St. Vith are now a part of the proud heritage of the U.S. Army. His deeds are a perfect example of the impact a commander can have on a combat unit. Guided by Clarke’s leadership, CCB and the other elements of the "unlucky" 7th Armored Division held up the most formidable force the American Army has ever had to face. That’s decisive leadership in action!

Notes

1Merriam, Robert E., The Battle of the Bulge: Hitler’s Last Desperate Gamble to Win the War!, New York: Ballantine Books, 1957.

2Ibid.

3Borows, Stephen D. CPT, Clarke of St. Vith: Brigadier General Bruce C. Clarke’s Combat Command “B” of the Seventh Armored Division at the Battle of St. Vith, Belgium, Louisville, KY: University of Louisville, 1984.

4Clarke recounts the circumstances of CCB’s being alerted and his arrival at Jones’ headquarters in the U.S. Army Armor School’s publication, The Battle at St. Vith, Belgium, 17-23 December 1944, A Historical Example of Armor in the Defense, Fort Knox, KY: U.S. Army Armor School, 1966.

5Borows.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8Ibid.

9Clarke, Bruce C. GEN, Guidelines for the Leader and the Commander, Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1963.

10Ibid. Clarke goes on to say: “In World War II, those who served in armored divisions – and probably in other units as well – learned that mission-type orders were a requirement if the most was to be obtained from a command. … As the battle becomes more complex and unpredictable, responsibilities must be more and more decentralized. Thus, mission-type orders often will be used at all echelons of command and probably will be the rule at the division and higher levels. This will require all commanders to exercise initiative, resourcefulness, and imagination – operating with relative freedom of action. In our tactical forces, we have built-in organizational flexibility. We must recognize this and capitalize on it in our orders.”

11Ibid.

12Ibid.

13 Cole, Hugh M., The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1965.

14U.S. Army Armor School.

15MacDonald, Charles B., A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge, New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985.

16Borows.

17Whiting, Charles, Death of a Division, New York: Stein and Day, 1980.

18Borows.

19Ibid.

20U.S. Army Armor School.

21Borows.

email

email print

print