Measures of Effectiveness in Army Doctrine

“Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not so.” –Galileo Galilei

Measures of effectiveness (MoEs), while commonly defined across Army doctrinal publications, are explained in different and sometimes confusing ways throughout several manuals. For leaders seeking to measure the effectiveness of stability operations at the tactical level, this adds confusion to an already complicated and difficult task. Given the central function of MoEs in evaluating mission success, and the difficulty of conducting successful stability operations, doctrinal guidance on this topic should be as clear, useful and straightforward as possible.

This article will outline how MoEs are currently understood and used in Army doctrine, and will give recommendations on how doctrine can be adjusted to give more useful guidance on the use of MoEs to Army leaders, particularly those conducting stability operations in the contemporary operating environment (COE).

Definitions

Doctrinal definitions from Army Doctrinal Reference Publication (ADRP) 1-02, Terms and Military Symbols:

- Assessment – (Department of Defense (DoD)) 1. A continuous process that measures the overall effectiveness of employing joint force capabilities during military operations. See Field Manual (FM) 3-07, Stability Operations. 2. Determination of the progress toward accomplishing a task, creating a condition or achieving an objective. (Joint Publication (JP) 3-0, Joint Operations)

- Endstate – (DoD) The set of required conditions that defines achievement of the commander’s objectives. (JP 3-0)

- Measure of performance (MoP) – (DoD) A criterion used to assess friendly actions that is tied to measuring task accomplishment. (JP 3-0)

- MoE — (DoD) A criterion used to assess changes in system behavior, capability or operational environment that is tied to measuring the attainment of an endstate, achievement of an objective or creation of an effect. (JP 3-0)

- Indicator – (Army) In the context of assessment, an item of information that provides insight into an MoE or MoP. (ADRP 5-0)

Understanding effects – academic underpinnings

It is imperative to understand that regardless of what planning process or paradigm is used, our actions create effects, and there has to be an attempt to measure our effects by doing more than just measuring performance. Actions will result in effects, both positive and negative. These effects encompass the full range of possible outcomes (or consequences of actions) across the full spectrum of conflict and occur at all levels of war.1

Within the operational environment, we are trying to determine causation to develop actions to reach a desired outcome (endstate). The COE consists of complex problems, and our planning process demands we know as much as possible about the situation if we are to develop actions to create the necessary conditions for the desired endstate. Part of the planning process is to predict the outcome from our actions taken. This can be an extremely complex task when each problem is distinctive unto itself, yet together shape the operational environment and can make it difficult to predict effects from individual actions.2

While we can rarely be certain of an outcome, we make assumptions based on existing facts to establish causation between actions and results. These facts should include past inputs and their outcomes. During this process, we must be careful to distinguish between correlation and causation. Correlation means that two events tend to occur together with some frequency, but this does not necessarily imply causation.

We can only determine causation by developing a hypothesis, which will attempt to find the correct way of linking our actions to the desired effects.3 Put simply, if we do “X,” we expect to get “Y” result. As with any hypothesis, there has to be a method for determining if we were correct. Here, it becomes important to include MoEs within the planning process to help facilitate success.4

A military-planning process wherein a planner must consider causation and correlation, and then attempt to predict effects on the operational environment, is similar to the scientific method in that they both attempt to establish a relationship between inputs and outputs. An input is simply what goes into the action taken (what are we doing); the output is the direct result of our input. For example, we can hypothesize that if patrols increase (input), then the local populace will be more secure (output). Some form of MoP can typically measure both the input and output, but neither of these can determine if there has been a decrease in violence. To determine this, we use the outcome, which is the change because of the output. Within the operational environment, the outcome is primarily determined by human behavior, which is gauged by MoEs.5

Joint doctrine, effects and assessment

Joint doctrine asserts that well-planned actions create effects to achieve objectives toward attaining an endstate.6 Working through this process means nesting objectives, effects and endstates. They must be understood to successfully achieve desired goals.7 JP 3-0 states, “An objective is the clearly defined, decisive and attainable goal toward which every operation is directed, or the specific target of the action taken. It is aimed toward a given purpose – the purpose being the why.”

From objectives, the endstate is the set of required conditions that defines achievement of these objectives. Since military operations are by nature actions, and actions create effects, this would imply that the goals for objectives should include desired effects. This establishes a direct relationship between actions to effects, and to the desired endstate.8

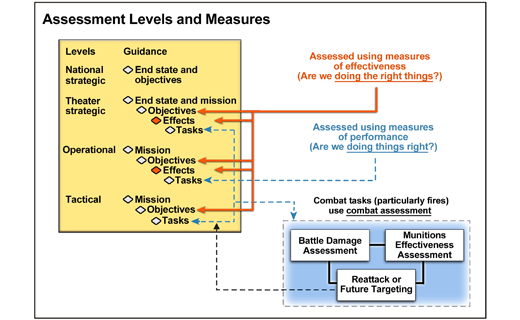

JP 5-0 states that assessment occurs at all levels and MoEs are created to support strategic and operational mission accomplishment.9 At the tactical level, missions, objectives and tasks are to be assessed, while effects are measured above the tactical level. This way of thinking supposes that commanders’ actions at the tactical level cannot be gauged within their areas of operation (AOs). However, effects at the tactical level should also be assessed to fully integrate tactical-level actions with the broader operational picture. The effects of tactical tasks are often physical in nature, but as JP 5-0 states, can also reflect the impact on specific functions and systems.10 Tactical objectives are usually associated with a specific target; however, according to doctrine, this action will result in some effect. The tactical level of war does not exist in a vacuum, and tactical operations create effects that have to be understood at the tactical level to help higher-level commanders better understand conditions in their AOs.

This gap in current doctrine is depicted in Figure 1. MoEs are used to assess objectives and effects at the strategic and operational level, yet are only used to assess tactical objectives. While each level of war and command have endstates, their endstates are in reality objectives to meet the strategic endstate, as shown with the national and theater level guidance in Figure 1. To work toward the endstate, the lowest levels of war must ensure their objectives are working toward the endstate. JP 5-0 states that “[c]ommanders who are skilled in the use of operational art provide the vision that links tactical actions to strategic objectives.”11 To ensure objectives are met is to assess effects, which can only be accomplished with MoEs; otherwise, we run the risk of only assessing input.

JP 3-0 states, “The operational environment is a composite of the conditions, circumstances and influences that affect the employment of capabilities and bear on the decisions of the commander.”12 Also, the operational environment is influenced by military actions that cause effects. As such, large-scale operations down to the smallest battle will result in some effect, likely indirect, that either works for or against the desired endstate. Likewise, a “good” commander’s intent is based on effects.13 The outcomes of tactical actions must be tied to strategy via the operational level of war, and this can be facilitated by including MoEs in tactical-level planning and analysis.

Assessment, stability doctrine and MoE

Building on concepts described in joint doctrine, Army doctrine also requires commanders to envision an endstate to their operations that consist of a set of future conditions describing successful completion of their mission. It further requires that continuous assessments be conducted to determine progress toward achieving this goal. As part of this continuous assessment, commanders and their staffs use MoEs to evaluate progress toward attaining the desired conditions and to aid them in determining why the current degree of progress exists.

This is the case in all types of military operations. However, during stability operations, using MoEs properly can be extremely challenging for leaders at the tactical level.

MoE

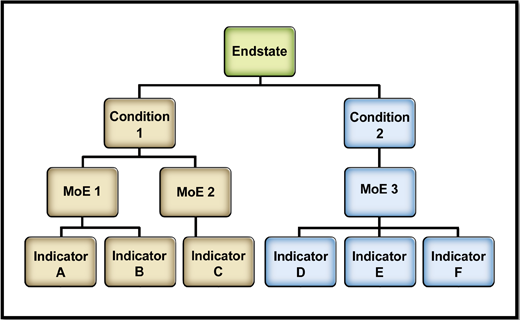

At their most basic level, MoEs should be developed to measure those items of information within the operational environment that give signs of progress toward creating the conditions described in the commander’s endstate. MoEs are evaluated using subordinate measurement tools called indicators, which are items of information related to the MoE. Each of the conditions may be measured by one or more MoEs, while each MoE may be informed by one or more indicators (Figure 2).

While simple to understand in theory, creating and choosing appropriate MoEs and their supporting indicators can be an extremely complicated task in practice. We need to know not only what to assess, but also how to actually assess it.14 This is no small undertaking, and deciding what to measure can determine whether there is actual progress toward the endstate. This makes the endstate that much more important. To fully reach any goal, the tactical level must be fully nested, which will require using MoEs to understand effects at the lowest levels because desired effects are nothing more than desired results from actions taken to achieve objectives.15 Unfortunately, doctrinal guidance on the subject is confusing and inconsistent, making it more difficult for tactical leaders attempting to make sense of it.

Chapter 7 of Army Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (ATTP) publication 5-0.1, Commander and Staff Officer Guide, contains some of the clearest and most straightforward doctrine on the subject. This section states that when selecting and writing MoEs, Soldiers should:

- Select only MoEs that measure the degree to which the desired outcome is achieved;

- Choose distinct MoEs;

- Include MoEs from different causal chains;

- Use the same MoEs to measure more than one condition when appropriate;

- Avoid more reporting requirements for subordinates;

- Structure MoEs so that they have measurable, collectable and relevant indicators;

- Write MoEs as statements, not questions; and

- Maximize clarity.16

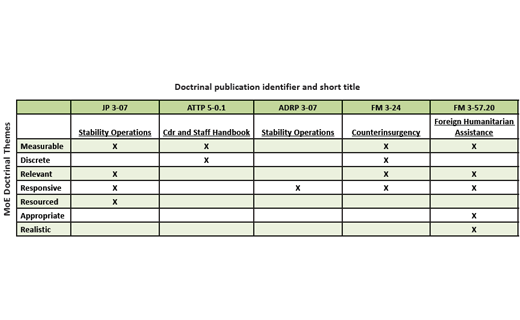

These guidelines are useful to tactical leaders and meant to apply to all types of operations. Several manuals relevant to conducting these types of operations – including FM 3-24, FM 3-24.2, Army Technical Publication (ATP) 3-57.20 and ADRP 3-07 – have their own guidelines for what should characterize an MoE. However, these guidelines are often incomplete, inadequate or address similar concepts with different terminology, and they can confuse the reader

For example, both FM 3-24 and FM 3-24.2 list the same four characteristics MoEs should have.17 However, many of these concepts are already addressed in the guidance listed in other manuals, albeit with different or less concise terminology (Figure 3). Only listing these four characteristics gives the impression they are the sole considerations that should be taken into account, and using differing terminology among doctrinal references can foster more confusion.

Indicators

Selecting and writing appropriate indicators to inform the evaluation of MoEs is another task that is simple in theory but difficult in practice, especially in complex operational environments. Joint and Army doctrine define and use indicators in different ways, and Army doctrine’s guidance is fragmented throughout several manuals. Understanding doctrine’s approach to developing indicators is critical to the success of assessment efforts.

ADRP 5-0 recommends that a mix of quantitative and qualitative indicators are used to evaluate MoEs to mitigate the risk of misinterpretation and overcome the limits of raw data in understanding complex situations.19 This is echoed in FM 3-24, which affirms this is necessary to effectively assess the social variables that are critical to mission success in stability operations.20 ATTP 5-0.1 provides some useful guidance on the subject by requiring that staffs develop indicators that are “measurable, collectable and relevant.”21 ADRP 3-07 adds a few worthwhile elements to this description by providing the following guidance for selecting and using indicators in stability operations:

- “In many cases, indicators that directly assess a given stability task are not available. In these cases, proxy indicators may be necessary. Proxy indicators are indicators that measure second-order effects related to the activity that forces need to measure.”

- “Effective forces consider responsiveness for selecting measurement tools in stability. In stability, responsiveness is the speed with which a desired change can be detected by a measurement tool.”

- “A single indicator can inform multiple ... [MoE].”22

This guidance is valuable, if a little scattered, forcing leaders to comb through multiple doctrinal sources to effectively use it.

A useful way for tactical leaders to think about indicators may be to define them along the same lines proposed by doctrine for defining evaluation criteria.23 Indicators could be broken down into five elements:

- Short title – the indicator name;

- Definition – a clear description of what the indicator is measuring;

- Unit of measure – may be quantifiable or qualitative;

- Benchmark – a value that would define the desired state in terms of the particular aspect of the operational environment being measured;

- Formula – an expression of how changes in the value of the indicator affect the MoE (i.e., is more or less better?)

While this paradigm may not be appropriate in every situation, this may help clarify the process for some leaders and make it easier to explain the logic of their assessment plan to commanders and their Soldiers.

Conclusion

Evaluating progress toward the desired endstate during stability operations can be a challenging and complicated undertaking. MoEs and their supporting indicators play a critical role in this process, making clear, useful and straightforward doctrinal guidance on the subject extremely important. Leaders need to have a clear understanding of this process to succeed in the COE. Investing more time and energy in making doctrine’s approach to the subject more coherent could potentially pay enormous long-term dividends.

Notes

1The Air and Space Power Course, “Effects-Based Operations,” U.S. Air Force.

2Ruby, Tomislav Z., “Effects-Based Operations: More Important Than Ever,” Parameters, Autumn 2008.

3Morrissey, Michael T. MAJ, “Endstate: Relevant in Stability Operations?” master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2002.

4Ibid.

5McCormick, Shon MAJ, “A Primer on Developing Measures of Effectiveness,” Military Review, July-August 2010.

6DoD, JP 3-0, Joint Operations, Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Aug. 11, 2011.

7Gardner, David W. MAJ, “Clarifying Relationships between Objectives, Effects and Endstates with Illustrations and Lessons from the Vietnam War,” master’s thesis, Joint Forces Staff College, Norfolk, VA, 2007, abstract.

8DoD, JP 5-0, Joint Operation Planning, Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Aug. 11, 2011.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

11Ibid.

12JP 3-0.

13Ruby.

14Ibid.

15Ibid.

16Department of the Army, ATTP 5-0.1, Commander and Staff Officer Guide, Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, September 2011.

17Department of the Army, FM 3-24.2, Tactics in Counterinsurgency, Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, April 2009; Department of the Army, FM 3-24, Counterinsurgency, Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, December 2006.

18Data for Figure 3 taken from JP 3-07, ATTP 5-0.1, ADRP 3-07, FM 3-24, ATP 3-57.20.

19Department of the Army, ADRP 5-0, The Operations Process, Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, May 2012.

20FM 3-24.

21ATTP 5-0.1.

22Department of the Army, ADRP 3-07, Stability, Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, August 2012.

23ATTP 50-0.1

email

email print

print