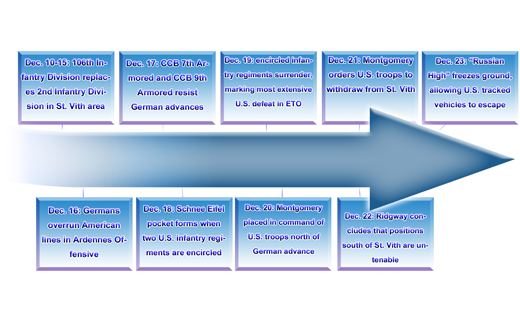

Saddles and Sabers: Timeline of St. Vith

School publication, The Battle at St. Vith, Belgium, 17-23 December 1944.)

Editor’s note: The U.S. Army marks the 70th anniversary of the Battle of St. Vith in mid-December 2014. Although another battle in the overall Battle of the Bulge, the battle for Bastogne, is better known, Armor and Cavalry defensive actions at St. Vith helped break the back of Hitler’s Ardennes offensive. As LTG Troy H. Middleton assessed in the foreword to the Armor School’s publication The Battle at St. Vith, Belgium, “Two of the most important tactical localities on the 88-mile front held by the VIII Corps in the Ardennes Forest at the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge … were Bastogne and St. Vith. Through these localities were the road nets that, if held, would disrupt the plan of any aggressor. Bastogne was an important communications center and was worth the gamble made for its defense. Its garrison wrote a brilliant chapter in history by denying the locality to the enemy; therefore, much of the comment pertaining to the Battle of the Bulge has centered around this important terrain feature. This fact has caused many to lose sight of the importance of St. Vith and the gallant stand made for its defense by elements of corps troops, by remnants of 106th Division and by [Combat Command B (CCB)] of 7th Armored Division. ... In my opinion, it was CCB that influenced the subsequent action and caused the enemy so much delay and so many casualties in and near this important area. Though Armor was not designed primarily for the role of the defensive, the operation of CCB was nevertheless a good example of how it can assume such [a] role in an emergency. Its aggressive defense measures completely disrupted the enemy’s plan in the St. Vith sector.” The same publication, in its introduction, stated, “The stand at St. Vith has been recognized by both German and Allied commanders as a turning point in the Battle of the Bulge.” ARMOR magazine brings you the good, bad and ugly regarding the Battle for St. Vith and the on-scene leadership that made the difference in the battle. First, the scene-setting.

Summary

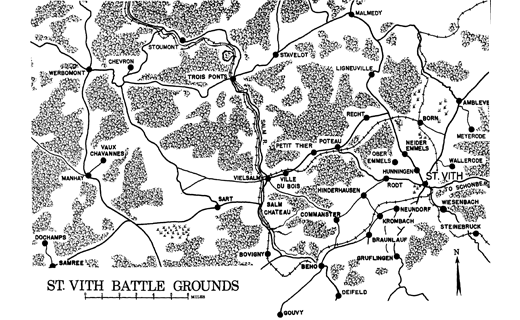

The Battle of St. Vith, which began Dec. 16, 1944, was part of the Battle of the Bulge. St. Vith represented the right flank in the advance of the German offensive, which intended a pincer movement on U.S. forces through the Losheim Gap and toward the ultimate objective of Antwerp.

The town of St. Vith, Belgium, was a vital road and rail center the Germans needed to supply their offensive. St. Vith was also close to the western end of the Losheim Gap, a critical valley through the densely forested ridges of the Ardennes Forest and the German offensive’s axis. Therefore St. Vith was a “must capture” by the German LXVI Corps and its 5th and 6th Panzer armies.

Opposing the Germans were units of U.S. VIII Corps. These defenders were led by U.S. 7th Armored Division and included 424th Infantry (106th U.S. Infantry Division), elements of 9th Armored Division’s CCB and 112th Infantry Regiment of U.S. 28th Infantry Division. Over the course of almost a week, 7th Armored Division – plus those elements of the 106th Infantry, 28th Infantry and 9th Armored Divisions – absorbed much of the weight of the German drive, throwing the German timetable into disarray before being forced to withdraw west of the Salm River Dec. 23.

Under orders from Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, 7th Armored gave up St. Vith Dec. 21, 1944, and U.S. troops fell back to positions supported by 82nd Airborne Division to the west, as noted. However, even in retreat, 7th Armored presented an imposing obstacle to a successful German advance. By Dec. 23, as the Germans shattered their flanks, the defenders’ position became untenable, and U.S. troops were ordered to retreat west of the Salm River. As the German plan called for the capture of St. Vith by 6 p.m. Dec. 17, the prolonged action in and around it presented a major blow to their timetable.

Dec. 10-15

The 106th Infantry Division (422nd and 423rd Regiments), a “green” unit, replaces the veteran 2nd Infantry Division Dec. 11 in the area of St. Vith and the Schnee Eifel (Snow Plateau). Parts of 106th are deployed east, with most of its force isolated on the Schnee Eifel. The 106th’s 424th Infantry Regiment is sent to Winterspelt. On the eve of the battle, the 106th is covering a front of almost 26 miles.

The 14th Cavalry Group, commanded by COL Mark Devine, moves into the area. Supporting 14th are 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion, with 12 three-inch towed anti-tank guns, and 275th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, with 18 M7 Priest self-propelled howitzers. The headquarters group also brings with it a second cavalry squadron (18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron) to screen the Losheim Gap, which is on 106th Division’s left flank.

The defenders’ battleground is the Ardennes. Most of the Ardennes is in southeastern Wallonia, the southern and more rural part of Belgium. The southern part of the Ardennes is also the northern section of Luxembourg, and on the southeast, the Eifel region continues into Germany. The region is typified by steep-sided valleys carved by swift-flowing rivers, the most prominent of which is the Meuse River. Much of the Ardennes is dense forests, with mountains averaging around 1,148 to 1,640 feet high but rising to more than 2,276 feet in the boggy moors of the Hautes Fagnes (Hohes Venn) region of southeastern Belgium. The Ardennes’ most populous cities are Verviers in Belgium and Charleville-Mézières in France, both exceeding 50,000 inhabitants. The Ardennes is otherwise relatively sparsely populated, with few of the cities exceeding 10,000 inhabitants – with a few exceptions like Eupen or Bastogne.

The two cavalry squadrons, 14th and 18th, set up fortifications in small villages in the area. This transforms them into isolated strongpoints guarding road intersections. Most of their supporting firepower comes from LTG Troy Middleton, commander of VIII Corps, who arranges for eight of his 13 reserve artillery battalions to support the area of the Schnee Eifel and the Losheim Gap, the central area of his front line.

Dec. 16

The German Ardennes-Alsace Campaign attack is thrown in force at U.S. 106th Infantry Division. A little before 5:30 a.m., a selective German artillery bombardment begins to fall on 106th’s forward positions on the Schnee Eifel, moving gradually back to the division headquarters in St. Vith. This attack cuts up most of the telephone wires the U.S. Army uses for communications. The Germans also use radio-jamming stations that made wireless communications difficult. This has the effect of breaking the defense into isolated positions, and denies corps and army commands information on events at the front line.

German soldiers find an undefended gap running between Weckerath to Kobscheid in the north. This movement coincides with a southern advance around the right flank of the Schnee Eifel through Bleialaf to Schoenberg, surrounding U.S. positions on the Schnee Eifel ridge. This double envelopment comes as a complete surprise to U.S. forces due to intelligence failures at First Army level.

LTG Courtney Hodges, commander of First Army, and Middleton commit combat commands of 7th and 9th Armored Divisions to support the 106th Division’s defense. MG Alan Jones, the 106th’s commander, sends reinforcements to Winterspelt and Schoenberg around noon. COL Charles Cavender of 423rd Regiment counterattacks, which retakes the village of Bleialf.

The Germans capture Steinebruck (six miles east of St. Vith), with its bridge over the Our River.

The only significant check in the German advance is at Kobscheid, where 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron had circled the village with barbed wire and dug in machineguns from their armored cars. Here, they hold the village for the day; after dark, they destroy their vehicles and abandon their positions, withdrawing to St. Vith. In other villages, the cavalry troops are forced to withdraw earlier in the day to avoid being surrounded and cut off. Devine directs the squadron to take up positions on a new defense line along the ridge running from Manderfeld to Andler, on the north side of the Our River.

Village strongpoints set up by the U.S. cavalry groups, plus sustained artillery fire from VIII Corps reserve units and 106th Division units, deny German units the roads.

Dec. 17

Before dawn, the German LXVI Corps renews its advance on the Our River. Winterspelt falls early in the day. The Germans then advance to the critical bridge at Steinebruck and past it, but are thrown back by a CCB 9th Armored Division counterattack.

BG Bruce Clarke, leader of CCB 7th Armored Division, arrives at Jones’ headquarters in St. Vith in the morning with news that his command is on the road to St. Vith but will likely not arrive until later that afternoon due to its progress being snarled on the roads. Adding to this bad news for Jones, who is hoping for deliverance by the arrival of organized reinforcements, the situation isn’t improved by the appearance of a demoralized Devine with news that German Tiger tanks are right on his heels. Devine is sent to a higher commander to make a “personal report.” With the appearance of German scouts on the hills east of town, Jones decides he has had enough. He turns over defense of the area to Clarke.

Clarke sees his first task as getting his command into St. Vith. By midnight he sets up the beginnings of a “horseshoe defense” of St. Vith, a line of units to the north, east and south of town. These units come mainly from 7th and 9th Armored Divisions but include troops from 424th Regiment of 106th Division, and various supporting artillery, tank and tank-destroyer battalions.

Dec. 18

As German troops mass on the opposite bank, 9th Armored blows up the bridge on the Our River at Winterspelt. Americans fall back to a defensive line with 7th Armored Division on the left and 106th’s 424th Regiment on the right. The Germans overrun Bleialf and Andler. The Germans capture the bridge at Schoenberg by 8:45 a.m., cutting off American artillery units attempting to withdraw west of the Our River.

The 106th Infantry Division’s 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments are encircled and cut off from the rest of the division by a junction of enemy forces near Schoenberg. After they receive an order from Jones at 2:15 a.m. to break out to the west along the Bleialf-Schoenberg-St. Vith road (Jones told them to “clear the area of Germans in the process”), they begin the breakout at 10 a.m., with COL Charles Cavender leading the attack (commander, 423rd Infantry). By nightfall both regiments had regrouped for a counterattack, covering three miles to the base of the ridge forming the east side of the Our River valley, and are prepared to attack and capture the bridge at Schoenberg at 10 a.m. the next day.

However, they are blocked by the enemy and lost to the division. The German southern pincer, advancing from Bleialf against scattered American resistance, closes at nightfall on the Schnee Eifel Dec. 17. Jones had given the troops east of the Our River permission to withdraw at 9:45 a.m., but it was too late to organize an orderly withdrawal by that time. This order, and the slow German southern arm, gave more Americans a chance to escape, but since they had newly arrived in the area and had few compasses or maps, most were unable to take advantage of the opportunity. The American positions east of the Our River become the Schnee Eifel Pocket.

Dec. 19

At 9 a.m., 422nd and 423rd’s positions come under artillery bombardment. The American attack on Schoenberg launches at 10 a.m. as scheduled, but comes under German assault-gun and anti-aircraft gunfire from armored fighting vehicles on the ridge to their front and from German troops firing small-arms fire. This is bad enough, but then tanks appear behind them and it is the last straw – the Americans are under fire from all sides and running low on ammunition. At this point COL George Descheneaux, commander of 422nd, decides to surrender the American forces in the Schnee Eifel pocket. At 4 p.m., this surrender is formalized, and the two regiments of 106th Division and all their supporting units, some 7,000 men, become prisoners of the German army. Among the prisoners is PVT Kurt Vonnegut of 423rd Infantry Regiment, whose experiences as a prisoner of war form the basis of his novel Slaughterhouse-Five.

A different group of scattered American soldiers numbering some 500 men surrender later, and by 8 a.m. Dec. 21, all organized resistance by U.S. forces in the Schnee Eifel pocket ends. This marks the most extensive defeat suffered by American forces in the European Theater of Operations.

Dec. 20

Supreme Commander GEN Dwight D. Eisenhower gives command of all troops north of the German advance to Montgomery, commander of 21st Army Group.

Forces of 82nd Airborne Division make contact with 7th Armored Division, meeting the condition Hodges set for command of the St. Vith forces shifting to XVIII Airborne Corps under LTG Matthew Ridgway.

Dec. 21

Holding St. Vith has become more of a liability to the Americans than an asset. Attacks from 1st SS Panzer Division have cut the Rodt-St. Vith road. The LVIII Panzer Corps’ advance south of St. Vith threatens to close a pincer around the entire St. Vith salient at Vielsalm, 11 miles west of St. Vith, trapping most of First Army.

The German attack on St. Vith begins at 3 p.m. with a heavy artillery barrage. The climax of the attack is the German 506th Heavy Panzer Battalion. Six of the titan Tiger tanks attack from the Schoenberg-St. Vith road against American positions on the Prumberg. Attacking after dark at 5 p.m., the tanks fire star shells into American positions, blinding the defenders, and follow up with armor-piercing shells, destroying American defending vehicles. Around 9:30 p.m., Clarke orders American forces to withdraw to the west. German forces pour into the town, happily looting the remaining American supplies and equipment, in the process creating a traffic jam that prevents pursuit of U.S. forces.

Dec. 22

Ridgeway arrives in Vielsalm. He is aware Montgomery has already decided to withdraw from the St. Vith area. Ridgway is still willing to consider holding positions in the area, but interviews with commanders change his mind.

Dec. 23

A “Russian High” begins blowing – a cold wind from the northeast and clear weather – freezing the ground and allowing free movement of tracked vehicles and the use of Allied air superiority. American forces are able to escape to the southwest, cross-country to villages such as Crombach, Beho, Bovigny and Vielsalm west of the Salm River. U.S. forces are able to outrun the panzers and join forces with XVIII Airborne Corps.

email

email print

print