Lost Sabers: Why We Need Operational Cavalry and How to Get It Back

winning the Starry Writing Competition. Retired MG Terry Tucker, a former Armor School commandant, is also pictured, far right, representing the Cavalry and Armor Association.

The U.S. Army has a maneuver problem. After more than a decade of brigade-focused warfare, our ability as a force to conduct decisive-action operations at echelons above the brigade has atrophied to the point of non-existence. Moreover, we have not only lost skills and experience operating at this echelon, we have dismantled key formations essential to operating at the division and corps level. While some of these organizations are returning, for the combat arm of decision, the most pressing concern is the loss of operational-level Cavalry formations.1 While tactical Cavalry formations have exploded in recent years, the last Cavalry unit organized, trained and equipped to fight at the operational level rode into the sunset in 2011 with the transition of 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) into 3rd Cavalry Regiment – a Stryker brigade combat team (BCT) in all but name and tradition. This appalling state of affairs must be rectified.

Why is operational Cavalry so important? Let us begin with a quick refresher on what Cavalry does complemented by examples of operational Cavalry in action. Cavalry performs three missions for the U.S. Army: reconnaissance, security and coordination/liaison duties. Also, Cavalry can also serve as an economy of force.

Current Army doctrine defines reconnaissance as “a mission undertaken to obtain, by visual observation or other detection methods, information about the activities and resources of an enemy … or to secure data concerning the meteorological, hydrographic or geographic characteristics of a particular area.”2 At the operational level, Cavalry is the first to make contact with terrain and the enemy, reporting on both and facilitating the advance of the following main-body formations.

Reconnaissance

In World War II, operational Cavalry proved its worth in reconnaissance beginning on the first day of combat in the European Theater of Operations. The 4th Mechanized Cavalry Group (MCG) confirmed the lack of enemy presence on islands dominating the approach to Utah Beach, materially aiding the success of VII Corps on D-Day.3 Corps Cavalry led Third Army on its massive end run through France and identified stiffening German resistance along the Moselle River. The 113th MCG rode through Belgium in less than a week, marking the route for the XIX Corps to follow.4 The 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron led Task Force Butler north into the French Alps, determining the fitness of routes and aiding that unit’s rapid advance.5 Cavalry probed the Siegfried Line throughout the fall and winter, determining its strengths and weaknesses. Finally, after the brutal fighting to advance to and across the Rhine River, Cavalry once more led the way, scouting routes and bridges for the advancing American columns.

Security operations

Security operations are less well known than reconnaissance. In fact, many times, the two are often confused by historians and military personnel alike. The problem lies in the concept that a unit conducting security operations is, almost by definition, also conducting reconnaissance. However, security operations are “those operations undertaken by a commander to provide early and accurate warning of enemy operations, to provide the force being protected with time and maneuver space within which to react to the enemy, and to develop the situation to allow the commander to effectively use the protected force.”6 Note how reconnaissance can be included in this doctrinal task, but the primary mission under security operations is protecting the main body, not finding the enemy. Furthermore, success in security operations is measured by the impact on the protected force and not necessarily on anything else. Thus, a unit conducting a security mission might be driven back 10 miles, but so long as the protected force is safeguarded, the loss of ground does not matter.

Security forces protect the main body by serving as its “crumple zone.” In offensive security operations, the Cavalry makes contact with enemy forces first, develops the fight, finds centers of resistance and passes this information back to the main body. Thus, the main body is able to commit its strength where it is most needed, and not haphazardly as it would in a meeting engagement. In defensive operations, unless a unit has absolutely perfect intelligence (a near impossibility), it generally has no way of knowing exactly where an enemy will commit his main effort, and thus the choice of where to commit strength is an educated guessing game. A defensive security zone helps solve this problem by absorbing the initial attack, identifying axes of advance, potentially defeating the enemy’s offensive security, inflicting casualties and hopefully forcing the enemy to fully deploy before reaching the main defensive belt. These actions allow the defender the luxury of choosing how to strike back even when it does not initially possess the initiative.

In the operational-security fight, Cavalry is echeloned in front, making the first contact, shaping the battle for the larger force, then handing the fight off to tactical Cavalry formations or main force units. Needless to say, with the inherent dangers of this role, operational Cavalry requires a unique mix of survivability, lethality and mobility.

In World War II, operational Cavalry screened divisional, corps and army flanks, fronts and rears with regularity in both offensive and defensive roles. The 2nd MCG fought through a German security zone in front of the Moselle in early September, and followed it with a grueling example of a defensive guard around Lunéville, wherein the Cavalry delayed a German counterattack long enough for XII Corps to respond to the danger on its flank.7 The 106th MCG guarded the flank of the XV Corps as it attacked through the Saverne Gap, identifying and slowing a German counterattack prior to handing off the battle to the infantry.8 Finally, throughout the drives to the Rhine and beyond, corps Cavalry protected the main bodies of their corps from German ambushes and flank attacks.

Beyond these and other high-profile missions, the Cavalry groups provided area security in corps and army zones, preventing significant losses to vital supply echelons. Also, Cavalry troops could also be found securing corps- and army-level headquarters due to their firepower and mobility.

Liaison/coordination

In addition to its combat roles, Cavalry also excels at liaison and coordination duties. When multiple formations are moving across the battlefield, their perimeters are areas of particular danger. Friendly units could engage one another, entangle their formations due to lack of traffic control or leave gaps in the line while assuming the other unit has taken responsibility. Some of these problems can be ameliorated through proper staff work and coordination. Technology also can ameliorate the problem. However, on the ground, there are still chances for things to go wrong, and technology can fail. The solution to this problem is for adjacent units to talk directly to one another and to establish physical coordination at contact points.

However, at the operational level, this solution becomes more challenging. Historically, entire units have been given responsibility to accomplish this task. This organization must be able to keep pace with both its parent and the unit with which it is trying to coordinate. Also, although this is an important task, it is rarely one that justifies committing line infantry or Armor formations. What is needed is a relatively small, mobile formation, with enough radios and combat power to talk, keep up and take care of itself without distracting from the main effort – in short, Cavalry.

Throughout the European campaign of 1944-45, Cavalry provided cross-boundary cooperation, particularly at the army and army group level. The unique configuration and equipment of the Cavalry particularly suited them to this role, as radio detachments could reside at adjacent headquarters to provide another radio net exclusively committed to lateral communications. In one notable instance, 6th MCG helped LTG George Patton knit together his Third Army across 475 miles of France.9 In situations where the next unit over might not only be from a different army group but a different nation, anything that could enhance communications between units was a good thing. Finally, the Cavalry had the mobility to quickly move to and establish contact points, the physical meeting of adjacent units. These points complemented radio coordination with face-to-face contact, weaving the two formations together.

Economy of force

Finally, economy of force is defined as “the allocation of minimal combat power to secondary efforts.”10 While this is a fairly obvious concept, the application becomes much more difficult in combat. An area that is secondary to the friendly force might not be so to the enemy. The Ardennes Forest in 1940 and in 1944 is a perfect example. Therefore, a unit conducting an economy-of-force mission must be robust enough to handle unexpected circumstances but not so large as to defeat the point of economizing combat power. The inherent mobility and combat power of American operational Cavalry made it often uniquely qualified to fulfill such a role.

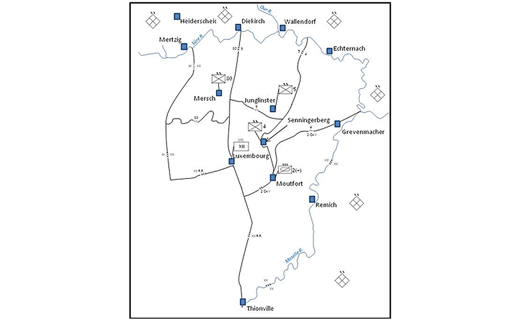

In 1944, 4th MCG covered such vast distances for VII Corps that it had to be relieved by an entire corps twice in nearly a month.11 The 3rd MCG covered half of the XX Corps’ sector in the fall of 1944, allowing for massed combat power in the November crossing of the Moselle.12 The 2nd MCG covered a corps’ worth of front along the Moselle in the winter of 1944-1945, allowing XII Corps to concentrate its infantry divisions on much smaller fronts (Figure 1).13 The 11th, 15th and 113th MCGs helped Ninth Army stretch its limited resources over a large front during the Ardennes offensive.14 American forces gained success on the attack by massing combat power, attacking with regiments or even divisions in column. Yet operational requirements so stretched American units that they became used to attacking with no reserve.15 These two facts should have been mutually exclusive. However, the presence of the Cavalry helped corps and army commanders meet that need. Without the important capabilities offered by these formations, it is doubtful that the Americans could have succeeded, given the already stretched nature of the line formations.

Need for operational Cavalry

While the above examples all stem from World War II, it is not the only modern conflict where these formations have proved valuable. In Korea, the lack of operational Cavalry allowed for serious surprises to befall the United Nations forces south of the Yalu River.16 In Vietnam, 11th ACR proved its worth in area security operations throughout the country. In Operation Desert Storm, 2nd ACR led VII Corps into the Iraqi Republican Guard, while 3rd ACR maintained the connection between VII and XVIII Corps. Finally, in 2003, 3-7 Cavalry demonstrated that a divisional Cavalry squadron equipped with modern technology could serve at the operational level, protecting the advance of 3rd Infantry Division to Baghdad.

Since 2003, the U.S. Army has not had the need to maneuver more than one BCT at a time across the battlefield as it conducts wide-area security missions in pursuit of insurgents and terrorists in Iraq and Afghanistan. Moreover, the Army is shrinking, and days of corps- and army-level maneuver are more than likely well behind us, if for no other reason that we no longer possess the capability of massing more than a couple of divisions in one place, and that would require the full resources of the military. In this world, does operational Cavalry still have a reason to exist? The answer is an unequivocal yes.

Although the days of corps maneuver are probably gone for the foreseeable future, for the modern Army, the division has assumed the operational role the corps held throughout much of history. Thus, while we will probably never again see a full corps deployed in action, there are multiple instances wherein two or more brigades might have to operate in tandem across the battlefield. In this instance, operational Cavalry comes to the fore. While both brigades might possess their own reconnaissance squadron, neither possesses the capability to perform traditional Cavalry missions for the entire force. Even if one BCT did surrender its reconnaissance squadron for the good of the division, that brigade would then lose its tactical Cavalry, making it less capable than designed, as well as defeating the doctrinal concept of echeloned security. Moreover, the current brigade recon squadron simply does not have the combat power to conduct high-intensity security operations without significant augmentation. While this approach worked in World War II, the modern U.S. Army cannot afford to have units incapable of accomplishing their primary missions without reinforcement.

While we might rely on technology to prevent surprise at the operational level, there simply exist too many ways to spoof, evade, jam or otherwise avoid sensors. Technology can enhance organizations but cannot replace them. Therefore, what is needed is a formation that can fill the niche of operational Cavalry without culling combat power from deployed BCTs. This future operational Cavalry must have the mobility to keep pace with high-tempo armored operations, the survivability and lethality to fight for information and conduct security operations, and the ability to be as self-sustaining as its next-higher-level organization.

Cavalry squadrons

While some might argue for a return to an ACR-level reconnaissance and security formation, this simply will not do.17 The Army designed the ACR to provide Cavalry functions to a corps. The ACR consisted of six battalions’ worth of combat power with an aviation squadron and an artillery battalion.18 In the Army of 2014 or 2025, placing such an organization in front of a divisional formation would simply be overkill and far too expensive to sustain. With the advances of technology, as well as the constraints of force structure in mind, the Army should structure its operational Cavalry around a squadron concept – much like the divisional Cavalry of the Army of the pre-modular era. These formations were the culmination of decades of historical and combat experience. It would be a shame to simply throw this knowledge away.

Where do these formations come from? An ABCT should be off-ramped and converted into about three heavy divisional Cavalry squadrons. While this is a controversial and painful recommendation, it is a necessary move unless funds can be found to raise a BCT’s worth of combat power. If the U.S. Army is serious about conducting decisive-action operations above the brigade level, operational Cavalry is an absolute requirement. Moreover, three squadrons of divisional Cavalry would give the force enough flexibility to conduct up to three division-level operations simultaneously or provide enough combat power for a sustainable rotation in prolonged operations like Iraq or Afghanistan.

Although the preferred course of action would be for each of these divisional Cavalry squadrons to be assigned to a parent division, another course of action might be that they are all assigned to a single BCT – resurrecting a Cavalry regiment. However, this organization would truly be modular in that the individual squadrons would be fully self-sufficient in logistics, and the regimental headquarters would exist for training and administrative functions only. This approach would also allow the armor force to create its own “elite” organization, serving much the same role as the old ACRs or 75th Ranger Regiment for the infantry. Finally, in extreme need, the entire Cavalry regiment could be deployed en masse to serve as corps Cavalry.

These new divisional Cavalry squadrons should look much like their predecessors, though with modifications for advances in technology. However, there will be some differences. Modern operational Cavalry requires aviation assets – modern history is persuasive in this regard. Originally, two troops of aero-scout OH-58s filled this requirement for divisional Cavalry. Unfortunately the Kiowa is being phased out. A troop of Apaches might provide some of the same capabilities, although the sustainment of even a single troop of Apaches would strain the logistics of a squadron-level organization. Armed unmanned aerial systems technology is not yet at the level where a squadron could effectively wield such an asset. Therefore, divisional Cavalry might have to rely upon habitual relationships with combat-aviation brigades for aerial support. This is not ideal, but gaps in capability might make this compromise a reality.

Another point of contention might be whether these squadrons should be like the old divisional Cavalry organization of only three ground troops, or like the ACR squadron of three troops and a tank company. The inclusion of the tank company will give the squadron more ability in the security role but might prove too expensive to include in a budget-constrained environment. However, the capabilities provided by the tank company are essential to the survivability of the organization in a high-intensity situation and should be included, as operational Cavalry must be able to fight and win without substantial augmentation. The older divisional-Cavalry model assumed that the ACR would be echeloned to the front providing the stand-alone cover mission – a justification that is no longer valid.

Finally, the artillery battalion attached to the force-provider BCT should be retained but have its batteries split, with one to each divisional Cavalry squadron. Cavalry, by its nature, will operate well forward of the rest of the division and cannot depend on fire support from the BCTs. Moreover, artillery support is essential to success in security missions as well as economy-of-force operations. Therefore, the Cavalry will need to bring its own guns with them without depriving the BCTs of their organic artillery. The success of 3rd ACR in operating decentralized artillery batteries has already proven the ability of such an organization to exist.

While the last half of this article has proposed many options, they are merely suggestions. There are many ways to achieve similar effects. However, the bottom line is that operational Cavalry must return to the force. The Army is more than simply a collection of brigades. It is a fusion of disparate elements, all with their own task, combining to achieve results greater than any of the individual parts could achieve. Going into a high-intensity conflict involving multiple brigades without operational Cavalry would be akin to crossing the line of departure without all your equipment – ill advised and needlessly assuming risk.

Notes

1Operational Cavalry refers to formations making an impact on the theater-level battlefield, either corps or division in the modern era. Tactical Cavalry are formations providing service to smaller formations.

2Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 1-02, Operational Terms and Graphics, Washington, DC: Government Publishing Office, 2004.

3 “4th Mechanized Cavalry Group After-Action Report, June 1944,” Entry 427, Record Group (RG) 407, National Archives II.

4Rose, Ben, editor, The Saga of the Red Horse, Nijmegan, Holland: N.V. Drukkerij G.J. Thieme, 1945.

5“117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron After-Action Report August 1944,” Entry 427, RG 407, National Archives II.

6FM 1-02.

7“2nd Mechanized Cavalry Group After-Action Report, September 1944,” Entry 427, RG 407, National Archives II, Sept. 18.

8“106th Mechanized Cavalry Group After-Action Report, November 1944," Entry 427, RG 407, National Archives II.

9Allen, Robert S., Patton’s Third U.S. Army – Lucky Forward, New York: Manor Books Inc., 1947; Unicorn Rampant – The History of the Sixth Cavalry Regiment/Group at Home and Abroad, Sixth Cavalry Association, 1951.

10FM 1-02.

11“4th Mechanized Cavalry Group After-Action Report, September 1944,” Entry 427, RG 407, National Archives II; “4th Mechanized Cavalry Group After-Action Report, October 1944.”

12“Patton's Ghost Troops” – After-Action Report 9 August 1944-9 May 1945,” Phoenix: 3rd Cavalry Veteran’s Association, 1974.

13“XII Corps Report of Operations December 1944,” 212, Entry 427, RG 407, National Archives II, Ops Map #8.

14The Ninth Army’s official history records the formation holding 40 miles with five divisions. Left out of the count were the Army’s three Cavalry groups. Conquer: The Story of the Ninth Army, Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1947.

15Doubler, Michael, Closing with the Enemy: How GIs fought the War in Europe, 1944-1945, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1994.

16The 1st Cavalry Division, despite the name, in the winter of 1950 was simply an infantry division by another name and not being used as Cavalry.

17MAJ Keith Walters argues passionately in his article “Who Will Fulfill the Cavalry's Functions?” for restoration of 3rd ACR. While he convincingly proves the need for reconnaissance and security, he focuses solely on restoring the ACR and not on other possibilities. Walters, “Who Will Fulfill the Cavalry’s Functions?” Military Review, Volume XCI, No. 1 (January-February 2011).

18Each of the regiment’s three Cavalry squadrons possessed 41 tanks, 41 M3 Calvary Fighting Vehicles and a battery of six M109s.

email

email print

print