1st Armored Division Leads Army in Re-examining Mission Command ‘Initiatives’

are MG Sean B. MacFarland, 1st Ar-mored Division commanding general; LTC

Michael A. Ellicott Jr., 1st Armored Division’s division engineer; and BG Joseph P.

Harrington, 1st Armored Division deputy commanding general for support. (Photo by SGT Ben J. Kullman, 1st Armored Division Public Affairs)

During 1st Armored Division’s recent distributed command-post exercise (CPX) Iron Resolve 14.2, the division leadership sought to re-examine and potentially adopt tried and proven mission-command methodologies that were once embedded within Army force structure but were set aside during the Army’s shift toward the brigade modularization critical to supporting the nonlinear, decentralized nature of the counterinsurgency (COIN) fight.

Previously, Cold War-era U.S. Army formations organized their staff structures and mission-command processes not only on the capabilities of then-available information-sharing technologies and prevailing knowledge-management techniques, but also on the centralized command and control (C2) needed to manage the fight of multiple maneuver brigades augmented with sizable numbers of attached supporting-arms formations. The 1st Armored Division’s challenge during Iron Resolve 14.2, therefore, was to revisit and reimagine these structures and processes prevalent more than two decades ago through the new lenses of 21st Century mission-command system technology and associated, updated information-sharing and knowledge-management techniques.

Iron Resolve 14.2’s main purpose was to practice mission-command and staff processes during expeditionary operations with a primary emphasis on offensive tasks. The desired endstate was a division staff trained on conducting mission command for decisive action and prepared for Network Integration Evaluation (NIE) 14.2. (During NIE 14.2, the division’s initial focus was on performing the role of higher control (HICON) for the brigade combat team (BCT) conducting the specific NIE experiments; it later transitioned from HICON to training audience, conducting a division-level joint tactical exercise that trained the division as a combined joint task force (JTF) headquarters.)

The division’s training objectives for this preparation included:

- Establish and operate a division command post (CP) to exercise mission command of decisive-action operations;

- Conduct and synchronize tactical operations by creating and maintaining a common operational picture using assigned digital systems;

- Validate and refine the division’s tactical standard operating procedures; and

- Execute daily reporting requirements and update briefs to higher headquarters according to the corps battle rhythm.

Mission-command capabilities now enable a division commander’s increased span of control of his formations. These capabilities appropriately (and in reality) implement the commander’s desired model of centralized planning and decentralized execution through mission-type orders. Divisions conducting decisive combat operations against a near-peer enemy within ULO will rely on such a model – and indeed will demand it.

For example, Joint Publication 3-31, Command and Control for Joint Land Operations, states: “Unity of command is necessary for effectiveness and efficiency. Centralized planning and direction is essential for controlling and coordinating the efforts of the forces. Decentralized execution is essential because no one commander can control the detailed actions of a large number of units or individuals.”

To adopt a revised version of this centralized mission-command methodology, Iron Soldiers experimented with adopting three “new” mission-command and staff organizational structures and processes to facilitate coordination, integration, synchronization and execution of fire and maneuver, to include operational fires for the division:

- The Joint Air-Ground Integration Center (JAGIC);

- The Deep-Operations Coordination Cell (DOCC); and

- Division artillery (DIVARTY).

Lessons-learned from Iron Resolve 14.2 indicated a significant learning curve is ongoing and will continue for the current generation of COIN-savvy warfighters within the division staff – and likely for the rest of our Army. The previous generations of Cold War Soldiers with training and experience on conventional combined-arms maneuver are nearly depleted from the force. Only the most senior officers and noncommissioned officers have the first-hand experience and historical knowledge of the warfighting skills necessary to succeed in the protracted and dynamic environment that characterizes ULO.

This point is amplified when considering the ability of division staffs to execute decisive operations against a potential near-parity, nation-state enemy. To address these ULO training shortfalls, the division is adopting accelerated collective-training programs and instituting fundamental staff and force-structure changes. The division is implementing these multiple command-and-staff structure changes concurrently as it supports the Army-directed NIE program at Fort Bliss, TX, and White Sands Missile Range, NM, while at the same time completing JTF headquarters training.

JAGIC

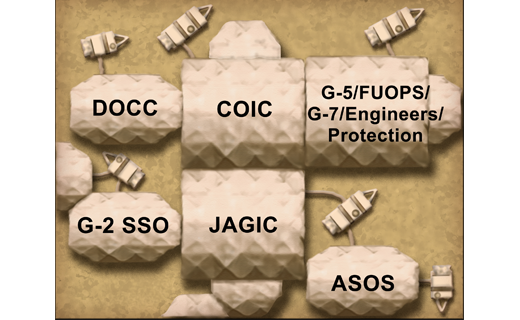

The division is adopting the JAGIC concept to expedite clearance of fires and airspace deconfliction within the division area of operations. The JAGIC evolved from a concept to enhance joint collaborative efforts to integrate joint air-ground assets. Located within the division Current-Operations Integration Cell (COIC), the JAGIC provides commanders a method to coordinate, integrate and control operations in the division-assigned airspace. The JAGIC co-locates decision-making authorities from the land and air components, coordinating fires to achieve the supported maneuver commander’s objectives and intent. The JAGIC facilitated effective mission execution while reducing the level of risk.1 In short, the JAGIC concept brings the air-support operations center down to the division level instead of maintaining it at corps level.

The JAGIC’s design fully supports and enables division-level current operations through the rapid execution and clearance of fires and airspace deconfliction. It is a modular and scalable center designed to integrate and synchronize fires and airspace control within the division area of operations according to guidance received from the division commander and the joint-force air-component commander.

As expected, integration of the JAGIC into 1st Armored Division’s Division-Main (D-Main) CP provided improved airspace deconfliction and coordination. The ability to dynamically retask previously distributed joint air assets in real time to support the division commander’s priorities allowed the staff to fully execute the detailed integration of fires. Through the course of two division exercises, JAGIC integration has proven to be a success; however, this hasn’t been without challenges. First, the current division fires cell, air and missile defense (AMD) and G-3/Aviation sections are not organized to man the JAGIC. Also, going into these exercises, the staff did not fully understand the roles, responsibilities and functions of each JAGIC member.

Current fires, AMD and G-3 Aviation manning are designed around the division’s CPs, principally D-Main and Division-Tactical (D-Tac). The current structure has evolved to support a COIN fight focused on personality targeting in a slower-developing environment and not on the execution of unified action or a deep-targeting effort. Given this organization and pace, modern CPs are often tied to product development in support of battle-rhythm events (i.e., commander’s update, battle update and battle-update-assessment briefings). These functions are manpower-intensive and were disrupted when the staff transitioned to JAGIC integration.

As outlined in Army Training Publication 3-91.1, The Joint Air-Ground Integration Center, the JAGIC is an execution cell and, as such, use of it to its full capability requires a mindset shift away from the management of the several asymmetric brigade areas of operation to the prosecution of the division’s fight. To doctrinally man the JAGIC, 212th Fires Brigade had to provide augmentation to the division’s fires cell while still meeting its own significant, competing demands.

During the initial integration of the JAGIC into the division’s mission-command structure, 1st Armored Division was supported by representatives from the Air Force’s Air Combat Command and the Army’s Fires Center of Excellence. These experts brought standardized battle drills that had been developed during previous exercises with hopes of using Iron Resolve 14.2 as further validation of the JAGIC concept. Following the CPX, JAGIC members from 1st Armored Division and 7th Air Support Operations Squadron (ASOS) used this expert assistance to develop a training program that further defined roles and responsibilities, and refined the battle drills for use in a less controlled environment. These efforts developed situational understanding among the staff and drove adjustments to the division’s COIC layout to allow full integration of the JAGIC.

DOCC

Division deep operations normally focus on the main defensive belt, second-echelon units and support. Fire support for deep operations may include the fires of field artillery, rockets, missiles and air support, as well as lethal and nonlethal C2. Usually, targeting for lethal and nonlethal attack focuses on planned engagements. A planned engagement entails some degree of prearrangement such as general target location, weapon-system designation and positioning, and munition selection. Planned engagements may be scheduled for a particular time or may be keyed to a friendly or enemy event. Other planned engagements may be specified by target type and may be on-call based on the characteristics of the target – for example, dwell time or high-payoff considerations. Unplanned or dynamic targeting may be conducted, but they must satisfy the same relevancy criteria as those of the planned engagement.2

The DOCC was historically adopted at the corps-level headquarters, with limited division employment, as a mechanism to facilitate targeting and synchronizing combat enablers in support of movement and maneuver. The DOCC’s mission is to apply operational fires (lethal and non-lethal) according to the commander’s guidance to create the conditions for success on the battlefield. The DOCC was traditionally chartered with three tasks to achieve the commander’s intent:

- Facilitate maneuver in depth by suppressing the enemy’s deep-strike systems, disrupt the enemy’s operational maneuver and tempo, and create exploitable gaps in enemy positions;

- Isolate the battlefield by interdicting enemy military potential before it can be used effectively against friendly forces; and

- Destroy critical enemy functions and facilities that eliminate or substantially degrade enemy operational capabilities.3

The DOCC normally consists of representatives from aviation, fires, G-2 and G-3 planners, with additional support from the electronic-warfare officer, air-defense officer, air-liaison officer, information operations, Staff Judge Advocate and civil-affairs representatives as required.

With these doctrinal principles in mind, and within the exercise conditions, the division established an ad hoc DOCC adjacent to the JAGIC. The division did not have enough manning to stand up a full-time DOCC organization due to the requirements to staff the COIC and JAGIC. While the COIC focused entirely on supporting the BCTs’ current fight within the next 24 hours, the DOCC focused on targeting and coordinating intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) assets in support of near-term operations for the 24-48-72-hour time periods; the DOCC therefore did not attempt to plan fires beyond the 72-hour air-tasking-order cycle. G-5 Plans was focused on planning operations beyond the 72-hour threshold and the division’s contingencies.

While DOCCs previously existed at the corps, given the expanded capabilities and responsibilities allocated to Army divisions, this cell is necessary to execute the division’s fight beyond the coordinated fire line (CFL). The primary lesson-learned from this initiative was how the DOCC was used to bridge the gap between plans and current operations, setting the conditions based on both time and events. Using these factors as entry arguments (time: 12-24 hours; event: next decision on the decision-support matrix), the staff was able to focus efforts by prioritizing finite resources to shape the deep fight. The increased capability of Army tactical missile systems and guided multiple-launch rocket systems, and the shift in Army aviation doctrine from cross-forward-line-of-own-troops to close-combat attack, provided the division more abilities to engage targets within and beyond the CFL, well within even 12-hour planning thresholds.

Development of the DOCC also forced the staff to break out of COIN-centric thought process to identify the division’s place in ULO. This paradigm shift reintroduced the concepts of depth and shaping to the organization.

DIVARTY

While the Army initiates the implementation of DIVARTY within the current force structure, the division is rapidly moving forward with the requisite manning and tactics, techniques and procedure (TTP) changes necessary to (re)adopt the DIVARTY concept according to U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM)’s DIVARTY implementation order dated April 9, 2014. These changes included converting 212th Fires Brigade to 1st Armored Division’s DIVARTY with an effective date of July 23, 2014, and transferring authority between the BCT and DIVARTY commanders for the incremental attachment of the BCT field-artillery battalions no later than January 2016.4

A DIVARTY is to be assigned to each Active Component division and ideally stationed with the division headquarters. The DIVARTY has no organic firing units but can be provided a variety of field-artillery battalions (rocket and cannon) and other assets as required to accomplish its mission for the division commander. The DIVARTY’s primary role is to coordinate, integrate, synchronize and employ fires, including operational fires, for the division commander. DIVARTY’s role further includes the ability to mass fires, employ radars, plan and oversee resupply rates and, importantly, execute division-level suppression of enemy air defenses. The DIVARTYs will provide mission command for training management and certification of the BCT field-artillery battalions and fire-support cells. The DIVARTY will work with the division fire-support cell to achieve coordination, integration and synchronization of fires.5

Although the transition of 212th Fires Brigade to 1st Armored Division’s DIVARTY is officially codified in the aforementioned FORSCOM order, this effort began months earlier. Based on recent initiatives to reduce the size of division staffs, 1st Armored Division began an alignment in August 2013 of the division fires cell and 212th Fires Brigade staff to find and leverage efficiencies between their redundant capabilities. During Iron Resolve 14.2, this initiative came to fruition through the integration of 212th’s fire-support and targeting sections into 1st Armored Division’s JAGIC and DOCC, and the management of the division’s counterfire fight out of the fires brigade’s tactical-operations center. Outside the exercise construct, 1st Armored Division has further solidified this relationship by attaching the BCT fires battalions and division fires cell to DIVARTY.

A division rebuilding and relearning

The Old Ironsides division commander is leading a concerted and focused effort across all warfighting functions to ensure 1st Armored Division’s prominent role in supporting an expeditionary Army. Simultaneously, the division has assimilated the current lessons-learned from the decentralized brigade- and battalion-level COIN operations of the past 13 years while reinvigorating many tested warfighting practices that were commonly practiced before 9/11. The commander is setting in motion the structural changes and TTP adjustments necessary to support the dynamic and potentially chaotic pace of decisive action against a range of enemy capabilities within ULO.

The division is incorporating the lessons of the past 10 years by adjusting the way the D-Main is manned and structured to improve the division’s ability to leverage all joint and Army fire-support assets. The leadership faces some exceptional challenges, however, as it attempts to make these structural and functional changes. Challenges include:

- The division’s anticipation of a manpower reduction within its headquarters and headquarters battalion (HHBN) from 775 personnel to around 500; despite this reduction, 1st Armored Division maintains the requirement to simultaneously, functionally man D-Main and D-Tac headquarters elements as well as the HHBN life-support area (LSA).

- The division will also require more transportation assets not currently on the HHBN modified table of organization and equipment (MTOE) to physically move and establish these multiple headquarters elements.

- Lastly, the HHBN MTOE does not support a functional LSA required to enable the D-Main headquarters. The current MTOE lacks maintenance and dining facilities, a battalion aid station and sleep areas – all essential to supporting an expeditionary headquarters. These facilities would need to be either built or contracted to meet the division’s daily support requirements.

With the demise of the division support command (DISCOM), mission command for division support-area operations is resurfacing as a significant challenge, one that is currently the responsibility of the task-organized maneuver-enhancement brigade (MEB). There are not enough MEBs allocated to the current Army force structure to cover down on all active divisions. There are currently only two active-duty MEBs; 19 MEBs are assigned to the Reserve or Guard components.

The historical role of DISCOM’s Division-Rear (D-Rear) area mission was to provide division-level logistics and health-service support to all units of the division. In addition to its assigned mission to provide direct support to the fighting forces and general support to the entire division, DISCOM also planned, coordinated and supervised base and base-cluster defense operations within the division support area. It did this in conjunction with D-Rear.

It is important to note the sustainment elements do not work for division commanders. They are instead an area asset that works for a corps-level sustainment command with a logistical footprint that is often larger than a typical division-rear area.

In essence, the Army removed from the division force structure a key capability, complicating how heavy divisions train. Overcoming these challenges will require force-structure realignments above and beyond division authority.

By implementing these division internal-structural initiatives, 1st Armored Division is providing more tools, processes and systems necessary to support the commander's rapid decision-making within the operations processes of plan, prepare, execute and assess. The collective structural changes should help reinforce a battle rhythm that supports both the division and subordinate BCTs by streamlining functional activities within a single action cell. Co-locating directors and planning staffs across functional warfighting areas within the JAGIC and DOCC enhances joint collaborative efforts to secure joint fires and ISR assets in support of the division. This structure also facilitates targeting and synchronizing combat enablers in support of movement and maneuver.

The experience of Iron Resolve 14.2 confirmed that the division fight centers on coordinating ISR and fires in support of subordinate BCT operations. These “sometimes new” and “sometimes old” staff and force structures provide 1st Armored Division the means to assume and indeed win this fight.

The division employed and refined many of the ideas and processes mentioned in this article as part of the joint training exercise and the Army’s NIE. It is clear that much of the Army’s knowledge and expertise required to execute the once-vaunted AirLand battle doctrine has atrophied. The hard-won lessons-learned from 1st Armored Division’s CPX program suggest, however, that 1st Armored Division leads the Army in re-examining, relearning and indeed reimagining these core ULO-centric competencies and capabilities.

Notes

1Wertz, Stephen A., “Joint Air Ground Integration Center,” Fires Journal, March 2012, http://www.readperiodicals.com/201203/2650589471.html.

2Field Manual 6-20-30, Tactics, Techniques and Procedures for Fires Support for the Corps and Division Operations, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, U.S. Department of the Army, 1989.

3Sevalia, Roy, “Fighting Deep with Joint Fires,” Call Newsletters, 2003.

4FORSCOM DIVARTY implementation order, FORSCOM headquarters, Fort Bragg, NC, April 9, 2014.

5Whitepaper, “Field Artillery Brigade/DIVARTY” (staffing version), U.S. Army Field Artillery School, Fort Sill, OK, 2014.

email

email print

print