Lessons from the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi Revolt: Analysis of the Writings of Iraqi Army Officer and Military Historian Mahmood Al-Durrah

Republished from ARMOR, November-December 2008 edition

(Author’s note: Among the problems of Saddam Hussein’s regime was the downfall of Iraqi scholarly thought and publications. Many Iraqi historians, political scientists and writers within Iraq were reduced to publishing works that did not contain true analysis and discussions of the problems facing Iraq’s modern history; instead, the focus was on slogans of Ba’athism and praising the regime. As a reader of Arabic books on military and political history, it is my earnest hope that among the fruits of Operation Iraqi Freedom is the reawakening of the true scholarly potential of Iraqi intellectuals.

This article discusses the writings of the late Iraqi officer Mahmood Al-Durrah, who served as an army lieutenant during World War II. Al-Durrah, an Iraqi military historian, shares his views on the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi conflict in his book, Al-Harb Al-Iraqi-yah Al-Britaniah (The Iraqi-British War, 1941).

When American soldiers or sailors hear “1941,” they remember Pearl Harbor; for Iraqis, it is the invasion of Iraq by British forces to suppress the pro-Axis government of Prime Minister Rashid Ali Al-Gaylani, who was installed as prime minister in a military coup that swept aside the Iraqi Hashemite monarchy. Al-Harb Al-Iraqiyah Al-Britaniah offers a comprehensive study of the strategy and tactics of British and Iraqi forces, and discusses how the British secured the port at Basra and fought their way to Baghdad. Al-Durrah provides perspectives on operational and tactical decisions made by Iraqi senior officers in confronting new British combined armor, infantry and air tactics. It also offers lessons on how the Iraqi military entered Arab political life.)

As U.S. forces become involved in the positive evolution of Iraq, as well as battling the Iraqi extremist insurgency, it is vital to study Arabic works written by Iraqis. These works not only should be read by American students of warfare but also need to be rediscovered by Iraqi security forces, who have sadly endured two decades of devolution in Iraqi military thought.

The chief cause of the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi conflict lay in the very structure by which modern Iraq was created. After World War I, during the 1921 Cairo Conference, British officials such as Winston Churchill and T.E. Lawrence, and the Hashemite family of the Hijaz (Western Arabia) who led the Arab Revolt, gathered to stitch together modern Iraq from the Ottoman provinces of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra.

After Prince Faisal was ejected by the French in 1920 and denied kingship of Syria, it was in Iraq that the British would find a convenient monarchy to install Faisal. It also provided the British with a method of giving their mandate in Iraq the veneer of Arab governance. The installation of Faisal as king of Iraq represented many negative images to average Iraqis, which included a Sunni ruling over a Shiite-majority nation, a British-inspired monarch and a Western Arabian (Hijazi) with no connection to Iraq.

The Iraqi monarchy and constitution was created from 1921 to 1923 with British oversight. This was a time when many Arab officers demobilized or simply defected from the Ottoman army and were experimenting with ideas of nationalism, self-determination and even fascism. The Iraqi constitutional monarchy was created to primarily preserve British basing and oil interests in Iraq, which was further cemented by the 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty that ensured favorable terms for the British and control of strategic military bases, primarily the Habbaniya Air Base, and valued oil fields. The terms of the 1930 treaty led to the suicide of Iraq’s Prime Minister Abdel-Mohsen Saddoun, who could not endure the humiliation of the terms the British dictated.

The 1930 treaty led to mass demonstrations, including an infamous riot orchestrated by GEN Yassin Hashimi, who would become prime minister in 1935. In this climate, Iraqi officers dreamed of being the next Kemal Ataturk or Reza Shah, both military officers. Ataturk founded modern Turkey, and Shah founded the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran. Other Arab officers in Iraq also saw solutions in the militant fascism of Hitler and Mussolini, who created a facade of order and industry using hidden violence and suppression of civil and political life.

Among the most influential military officers who infused the army into Iraqi politics was not a field commander but an instructor in Iraq’s military academy. COL Tawfik Hussein taught military history and injected ideas that inspired not only Al-Durrah but also a string of Iraqi military leaders who would orchestrate a series of military coups. Hussein laced his history lesson with images of King Faisal betraying the aspirations of Iraqi, Syrian and Palestinian officers who left Ottoman service to fight against the Turks in the Arab Revolt in the hope of establishing an independent Arab state. He argued that the Iraqi army had a duty to undertake political action to realign the direction of the nation. In 1929, Hussein began teaching and, by 1934, he had influenced more than 70 key officers and attracted the attention of the Muslim Youth Group, who yearned to re-establish the caliphate in Iraq. Two of the four generals in charge of the army – and who understood they held the key to maintaining internal order for King Faisal – were followers of Hussein’s rationale.

In addition, Lebanon became a haven for Iraqi officers who published pamphlets, as well as anti-monarchy and anti- British articles in the Lebanese press. More importantly, Lebanon offered a location to hold meetings with Islamists, Communists and nationalists, all committed to ridding Iraq of British influence.

1936 Bakr Sidqui military coup

It is important that all Arabs study what would become the first incidence in modern Arab political history where army officers staged a successful military coup in October 1936. The climate to create the perfect conditions for this military coup included the bulk of the Iraqi army being deployed on annual summer maneuvers; the army chief of staff being out of the country in London for military talks; and the cooperation of a flight commander who controlled five bombers, all under the leadership of GEN Bakr Sidqui. Events, which unfolded around the night of Oct. 26, 1936, began with a shock and awe of bombers under the command of Ali Jawad, screaming over Baghdad at 11:30 p.m. They dropped four bombs in front of the council of ministers’ building, the central post office, parliament and the Dakhla River, leading to seven casualties – but, more importantly, this was the first time aerial bombardments were used in a military coup.

The officers in revolt swore fealty to King Ghazi and sent a proclamation to the king indicating they were purging the corrupt ministers around him. Communists, led by lawyers in and around Baghdad, asked the people to rise up against the government. During the ensuing chaos, the war minister, Jafar Al-Aksary, was murdered by several officers sent by Sidqui. Sidqui imposed Prime Minister Hikmat Sulayman on King Ghazi, and Iraq was ruled by unconstitutional means for a year. Al-Harb Al-Iraqiyah Al-Britaniah laments the decision to execute Al-Askary, who dedicated his life to Arab nationalist causes and was a competent warrior, having distinguished himself fighting the Ottomans in the Arab Revolt; he also fought the French in Syria. Sidqui’s dictatorship would last less than a year, and he would be killed in an assassination plot hatched by military officers.

Iraqi politics after Sidqui would see the return of Prime Minister Nuri Al-Said for his fourth time as prime minister. Al-Said attempted to remove Iraq’s chief of staff, GEN Amari. Instead of Amari capitulating to the wishes of civilian authority, it was he and 30 senior officers who removed Al-Said from power and imposed Rashid Ali Al-Gaylani as prime minister. For added measure, the 30 senior officers, all yearning to return to the Sidqui dictatorship, deposed the war minister, Taha El-Hashemi.

Only one encampment, the Wishash Barracks, remained loyal to civil authority. The dictatorships of GENs Fawzy and Amari, along with Al-Gaylani’s, began in 1940 and would last until the end of the Anglo-Iraqi War in late May 1941.

World War II Iraq

During World War II, Iraqi officers and cadets saw a Britain that was on its last legs of empire. Many senior Iraqi generals and Arab nationalists assessed the situation and found that Britain stood alone: the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) had rolled over France, Poland and Czechoslovakia; Hitler had signed a nonaggression pact with Stalin; Iran’s Shah was pro-Axis; Turkey’s Ataturk remained neutral; Haj Amin Al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, had allied himself with the Nazis and was offering religious sanction for Arab officers to throw off their governments if those governments enabled British colonization; and London had requested that Baghdad abide by the provisions of the 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty and declare war on Italy and Germany.

Iraqi officers questioned why Iraq should continue its pro-British policies and have British oversight in policy matters when it was losing to the Germans. In a compact between Al-Gaylani and the senior generals, they decided that Iraq’s policy was to gain full independence for itself, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine to form a Greater Arab State. These five countries also formed a government that favored militarism; however, they stalled on declaring war on the Axis because the Axis recognized Arab self-determination; it declared no colonial ambitions in Egypt and Sudan and recognized their independence; it recognized the need for Arabs to be linguistically and culturally linked; and it was vehemently anti-Zionist.

There was a selective memory about Axis efforts to colonize Arab and African nations; for instance, the Italians colonized Libya in 1911 and began an invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. From 1940 to the start of hostilities between British and Iraqi forces, a series of negotiations were undertaken to get Baghdad to first declare war on the Axis; then allow access through Iraq for British forces; and lastly, react to London’s request for extra Iraqi security in and around two strategic British air bases at Habbaniyah and Baghdad.

Al-Harb Al-Iraqiyah Al-Britaniah addresses American diplomatic urgings for Iraq to cooperate with Britain as a means of asserting its right to full independence. This was the same line of reasoning the United States urged with Morocco: that Allied forces would, after World War II, work toward self-determination and independence of protectorates, mandates and colonies. The Iraqis, in turn, wanted Britain to assert the independence of Syria and Lebanon once they were liberated from the Vichy French, and demanded a just and lasting settlement of the Palestinian problem. (Then, as now, the Palestinian question was an agenda item of Arab governments.)

The British were in no mood for negotiations and expected the Iraqis to abide by the provisions of the 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty. Finer points of disagreement between the Iraqi and British governments dealt with unimpeded access to Iraqi facilities vs. the landing of British forces only with the consent of Baghdad. Such Iraqi indecisiveness in times of war would lead to the May 1941 British invasion of Iraq. What gave Britain’s Iraq policy a sense of urgency was the successful invasion of Greece by Nazi forces in April 1941, which made German bombers and transports within easy range of the Middle East.

It is important to understand the state of the Iraqi monarchy in 1940-1941. King Ghazi had died in a car crash in 1938, and in the world of conspiracies, the Iraqi “street” blamed his death on a British plot. In his place, the young King Faisal II was too young to assume the throne, so regency under his uncle, Prince Abdal-Illah, was declared. Prince Abdal-Illah saw the controversy between Al-Gaylani and the army vs. the British as a means of wrestling more power for the monarchy with British support.

British and Iraqi negotiations became crucial when Nazi forces solidified their hold on Greece and were moving on strategic islands such as Rhodes and Crete. The government of Al-Gaylani agreed to allow British forces to land in Basra but attached many conditions as to the size and use of roads by these and follow-on forces. The issue of follow-on British forces would be the spark that ignited conflict in May 1941. In the last week of April, British air, land and naval forces were making their way to Iraq from Bahrain, India and Palestine. The bulk of these ground forces would land in Basra, regardless of what Iraqi generals and ministers thought about follow-on forces. The stage was set for conflict.

Al-Gaylani revolt or Anglo-Iraqi conflict

Before delving into the tactics and operational aspects of this conflict, it is important to reflect on the choices Iraqi leaders made vs. how Morocco attained independence after World War II. Iraq saw in British weakness in the early years of the war (1939-1941) an opportunity to defy London and assert its sovereignty. Morocco, a French protectorate, and its monarch, King Mohammed V, chose to side with the Allied cause, contributing troops in the hopes that the removal of its status as a French protectorate would be the natural outcome after the liberation of France and the victory of the Free French. The outcome for Iraq would be a chaotic government after World War II, leading to the demise of the monarchy in 1958; for Morocco, it would lead to independence in 1956, with small skirmishes with French forces and a relatively easier removal of it protectorate status.

In Iraqi memory, the 1941 British landing would signify the second time English troops occupied Iraq, the first being 1914 to 1918. Little attention is paid to the reasons and geostrategic issues that drove London to send troops both times for the Iraqis, which is enough to say the British occupied Iraq twice during the 20th Century without a real comprehension of the historic or millennial geostrategic background of Mesopotamia.

Military balance of forces and disposition

In 1941, Iraq commanded about 46,000 active and 280,000 reserve army officers and troops and had 13,000 police officers. The Iraqis possessed a mixed number of Italian, British and American warplanes and transports, and one armored group composed of a mixture of antiquated tanks and armored personnel carriers. Unique to Iraqi forces was a riverine force of four armored patrol craft of 70 tons, armed with machineguns.

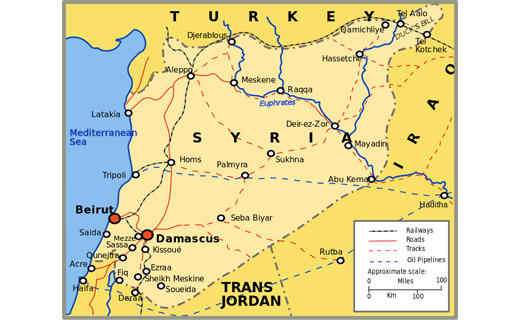

Iraqi forces were divided into three security regions: 1st and 2nd army groups, headquartered in Baghdad with garrisons in Fallujah, Baquba, Ramadi and Habbaniya Air Base (one of two in the country); 3rd Army Group, headquartered in Mosul; and 4th Army Group, headquartered in Basra with garrisons in Nasiriya, Diwaniyah, Amarah and Al-Shuayba Air Base.

Why Iraq’s military fate was sealed

Despite the British landing, a superior force both technologically and militarily, the main reason Al-Durrah attributes to Iraq’s defeat is what he calls “the governance of five” (the four military generals and Al-Gaylani). The four senior officers, GEN Salah-al-din Sabbagh, COL Fahmy Said, COL Mahmood Suleiman and COL Kamel Shabeeb, were each in command of an army group and had their own political ambitions and tribal groups to protect. As overall command-and-control of Iraqi forces was nonexistent, their military fate was sealed. An example highlighted in Al-Durrah’s book is when the Iraqi general staff drew up contingencies for the defense of Basra, these plans were ignored by field commanders, who took their orders from Sabbagh, the military governor of Basra.

The first wave of British forces were granted access into Basra by Al-Gaylani and arrived April 18, 1941. They were composed of 20th Infantry Brigade, an artillery regiment, an antitank battery, an engineer company and a civil affairs/humanitarian group. Their mission was to secure the port at Basra for follow-on forces that were to arrive April 27.

It was this second British contingent Al-Gaylani refused to grant access to, adding that British forces could not exceed one brigade in Iraq. On April 29, 1941, the British considered this refusal an abrogation of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 and tantamount to war. London refused to tie in any political concessions on issues – such as Palestine and Britain’s mandatory status over Iraq – to the landing of British troops on Iraqi soil during a time of war and national survival against Axis powers. Sabbagh remarked that by allowing this initial force unopposed into Basra, the battle for this strategic port city had been lost. Another problem of the Iraqis was that the only objective given to army group commanders was to be prepared to defend their regions. The British had clear objectives, which included first securing Basra and then the airfield at Habbaniya.

Strategic importance of Habbaniya Air Base

To demonstrate the importance of the Habbaniya airfield and its airport, Sin Al-Zuban, a secret communiqué from Berlin was dispatched by Mufti Kamal Haddad to guarantee Axis support to Al-Gaylani should war break out with the British. It also stated that an air bridge of resupply from the island of Rhodes would be provided, but pressed for the Iraqis to occupy Sin Al-Zuban airport and the Habbaniya airfield, as well as to secure sources of highly refined airplane fuel for German transports and fighter escorts. This Axis air bridge offered an important supply option for Iraqi forces since they had no access to Basra.

COL Haqi Abdel-Karim commanded elements of 3rd Army Group and took the initiative to lay plans for moving his group to secure Habbaniya Air Base. His forces would take positions around the base and attack once hostilities began with the British. Abdel-Karim worried about British air superiority in strafing his ground forces and breaking a siege of Habbaniya Air Base. His plan included a strategy to amass several artillery pieces across the Euphrates River overlooking Habbaniya Air Base to begin bombarding the base while conducting an infantry assault.

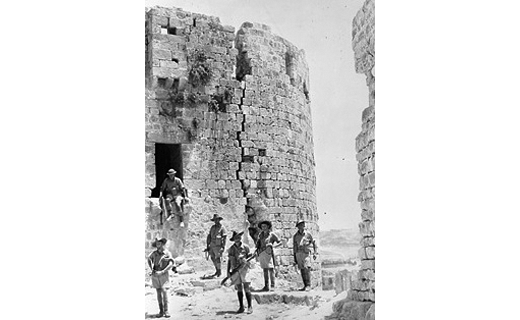

On April 30, the British base commander of Habbaniya awoke to find a massing of Iraqi troops around the perimeter and occupying the strategic heights of Talul overlooking the entire base. Immediately, the commander placed the base on alert, and mobile armored vehicles with mounted Vickers machineguns began taking positions along the perimeter. The Iraqis pushed forward tank, armored, machinegun and mechanized infantry companies supporting 4th Infantry Brigade, which had arrived from Kirkuk. They also reinforced this assault force with anti-air and engineering companies. British reconnaissance patrols revealed that 1st Infantry Brigade had moved from Baghdad to Ramadi to cut British reinforcements from Jordan. The Iraqis also moved their 11th Infantry Regiment from Baghdad to Fallujah by train to act as a reserve force that could respond using the village’s central location with its rail and river connections. The Iraqi generals and colonels then debated whether to make the first move and attack Habbaniya Air Base or wait for the British to strike first. The British continued their reconnaissance flights in Baghdad, Fallujah and Habbaniya sectors.

Capitalizing on airpower: new British realization

The Anglo-Iraqi War of 1941 saw maximum use of airpower by British forces and their Iraqi counterparts, as well as Iraq’s Axis allies. At 5 a.m. May 2, British bombers took off from the Al-Shuayba Air Base near Basra and the surrounded Habbaniya Air Base in the center of Iraq. Their target was Iraqi units surrounding Habbaniya Air Base that were not within artillery range. The British had prioritized their target list in the following order: artillery, tanks, armored carriers, trucks and infantry formations.

The Iraqis responded by shelling Habbaniya Air Base, beginning at 5:50 a.m., and sent up anti-air flak directed at British warplanes. The British aerial attack lasted 19 hours. Targets were drawn against Iraqi military assets in Baghdad, as well as Iraqi planes at the Rashid Ali Airstrip and troop barracks in Qurna. Four British Wellington bombers decimated Iraqi warplanes on the ground at the Rashid Ali Airstrip.

Sensing an imminent attack, and by observing the mass takeoffs of British warplanes, the Iraqis sent up their own fighters and bombers, which downed one Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter at Salman Pak and attacked British-held Sin Zuban Airport at Habbaniya. After the attack on the Rashid Ali Airstrip, the Iraqis dispersed their planes to airstrips at Baquba, Khan Bani Saad, Dilli Abbas and Mikdadiyah. However, good reconnaissance alerted the British to these other four airstrips and they attacked with aerial sorties, one of which scored a direct hit on the precious airplane-fuel storage facility in Baquba.

By May 4, only seven out of 69 Iraqi warplanes remained, and the only time the Iraqis would enjoy any air support was when Nazi Messerschmitt fighters and Henkel bombers flew to Iraq from bases in Rhodes and Syria (then controlled by the Vichy French). Iraqis and Germans could not coordinate Axis airpower with Iraqi ground operations against British forces. Instead, Axis warplanes stumbled on RAF fighters over Iraq.

The British employed a new tactic of keeping Iraqi units pinned in location using continuous aerial bombardment. Iraqis were unable to maneuver and support forces surrounding the British air base at Habbaniya. RAF planes located an infantry group traveling from Baghdad to Fallujah and strafed it. After almost two days of relentless RAF aerial bombardment against the Iraqis surrounding Habbaniya, a combined air and land force went to Talul Heights with infantry and armored Vickers machinegun regiments to mop up the concentration of Iraqi artillery and infantry forces surrounding the air base. Large British transports disgorged heavy artillery pieces at Habbaniya, which began shelling Iraqi artillery positions across the Euphrates River overlooking Habbaniya Air Base. On May 6-7, a combined British and Indian expeditionary force of two infantry brigades landed in Basra; these forces would be critical in bringing civil order in Basra.

Axis enters the fray

One of the most important lessons to be learned from the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi conflict is the impact that outside powers have on the potential outcome of warfare in Iraq, whether Vichy French Syrian, German and Palestinian guerrillas in 1941, or Syrian, Iranian and non-Iraqi Islamist extremist terrorist groups today. The Germans used Vichy French Syria to shuttle supplies and conduct air attacks in support of the Iraqis. These groups also used bases in Mosul, which offered the added benefit of access to fuel supplies.

On May 14-15, the British had had enough and launched air attacks on Mosul and Irbil in northern Iraq, and struck at airstrips and air bases in Damascus, Halab and Rayan, Syria. The British also maintained two remote fuel depots labeled H3 and H4 along the Jordan, Rabta and Baghdad roads, which would aid GEN Sir John Bagot Glubb Pasha’s Arab legions and British forces in Palestine to access Iraq during this crisis in support of British units.

Another item eerily similar to the 2003 war in Iraq was the use of guerrillas to harass regular forces. In this case, the guerrillas and so-called mujahideen from Syria, Iraq and Palestine joined the irregular force led by Palestinian leader Al-Kaukji.

From May 19-22, British generals in Basra focused their efforts on Fallujah because the village offered a crossroads as well as rail and river links to Syria, Jordan and Palestine. The British staged a diversionary attack on Ramadi to deceive Iraqis into committing forces in that sector while the main thrust on Fallujah began at 5 a.m. May 19 with bombardment from 57 fighter-bombers. The Iraqis failed to stop an advance of combined artillery, infantry and mobile armored vehicles mounted with Vickers machineguns, and Fallujah fell. An Iraqi truck, laden with dynamite to destroy the iron bridge linking Fallujah and Baghdad, was strafed by sheer luck by a RAF fighter.

Hitler realized the importance of unfolding events in Iraq and signed a directive May 23 authorizing military aid, advisers, weapons, intelligence-sharing and communications with Iraqi resistance forces to bog down the British in Iraq. However, Hitler’s preoccupation with Operation Barbarossa and his eventual invasion of Russia sapped the effectiveness of Axis assistance to Iraq.

Fall of Baghdad

Al-Durrah’s book ends with criticism of the way Baghdad fell. Iraqi generals and colonels did not overcome and adapt to British tactics in using combined air, ground and artillery forces, along with the effective armored machinegun vehicles. Instead, Iraqi regular forces fought, predictably, a defensive action. Al-Durrah compares the plan for the defense of Baghdad as almost identical to the defense of Fallujah. The book describes how the defensive plan of Baghdad collapsed as soon as it encountered British regiments and aerial bombers. Generals and colonels, who were confident of British defeat and support of the Axis almost a year earlier, were now fleeing toward Mosul.

Britain returned the regency of Prince Abdal-Illah, and many of these generals and colonels were rounded up and subjected to an Iraqi military tribunal, thus ending the reign of Al-Gaylani and his four generals, who ran Iraqi affairs for a little more than a year. These generals were replaced by Nuri Al-Said, who would become prime minister for a fifth time. The war would assert the Iraqi monarchy’s executive authority until the revolution of 1958 that violently ended the Hashemite rule in Iraq and brought COL Abdel-Kareem Qassem to power.

Al-Harb Al-Iraqiyah Al-Britaniah offers American military planners an understanding of why Iraqis mistrust foreign intervention – in particular, why Iraqi leaders are highly sensitive to foreign basing rights, which is why routine agreements governing status-of-forces protection that enable a military exercise today are resisted and sometimes viewed with suspicion by many Arab governments. The challenge is to understand the history and keep reassuring Arab friends that such agreements are not designed to impinge on sovereignty. Unlike European colonial, mandatory and protectorate experiences that crafted documents to subjugate a region, current civilized nations and global powers in the 21st Century are working together to empower Arab countries in dealing with security challenges that impact us all.

Just as America’s military students spent much time studying Russian works during the Cold War, today’s conflict demands a comprehensive study of Arabic works like Al-Harb Al-Iraqiyah Al-Britaniah.

Bio

U.S. Navy CDR Youssef Aboul-Enein is currently serving as a counterterrorism analyst in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, International Security Affairs, Washington, DC. He has served in various duty assignments, including special adviser and Middle East country director, Islamic Military, Office of the Secretary of Defense. His military education includes the Naval War Command and Staff College, the Army War College Defense Strategy Course and Amphibious Warfare School. He received a bachelor’s of business administration degree from the University of Mississippi, a master’s of business administration degree and master’s degree from the University of Arkansas, and a master’s degree from the Joint Military Intelligence College.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print